By Oliver Thom

“F-ck, f-ck, f-ck, f-ck! We are so fucked! F——c-k!“

“F-ck, f-ck, f-ck, f-ck! We are so fucked! F——c-k!“

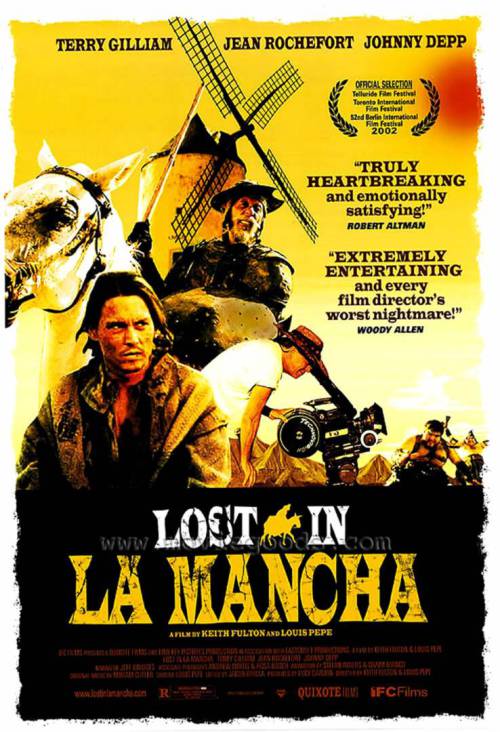

A featurette turned feature length fly-on-the-wall documentary, Lost in La Mancha is the last survivor of a filmmaking train-wreck for the ages, a film about a film that becomes a black box to director Gilliam’s The Man who Killed Don Quixote, the python’s unfaithful tilt at “Quixote” that exists somewhere between Cervantes and Twain.

The project itself, a slow burning obsession for Gilliam for over a decade before the cameras began to roll, sees Depp cast as a New York adman thrown back in time only to be mistaken by Rochefort’s Quixote as his own faithful squire, Panza. Vanessa Paradis is the absent love interest.

Arriving in Spain with a script rejected by Hollywood but made the Hollywood way without Hollywood money, his movie is to be undertaken with less than half the budget its script requires (and yet is to be the most expensive production ever financed on European money). It’s clear that the production will be the nearest run of things (one screw-up will kill the movie) and an obvious but not overworked parallel between Gilliam and Quixote develops. Fantasy will fight reality, but we already know who will win.

Gilliam begins pre-production without his principal cast (who have sandwiched the project into their already tight schedules), and alarm bells begin to ring. There is a denial that keeps “Quixote” moving, but the crew have worked with Gilliam before. With Gilliam everything is difficult, yet even “Munchausen” with its disastrous production was able to reach the screen; somehow the film can be made. But The Man who Killed Don Quixote won’t.

But the film has you convinced that it should be, and Gilliam is like a kid in a candy store – his enthusiasm keeps things going but it’s ultimately self-defeating. He casts a trio of lumpy giants and stomps around a test shoot; he fights with life sized string puppets in the guise of knights and guides the audience through his movie with storyboards and energetic script readings. He is in love and you can’t help but love him for it.

But by the first day of production the film already appears to be dead on arrival, extras remain unrehearsed and a location shoot is ruined by the near constant sound of NATO jets overhead. Gilliam films what he can. The second day sees torrential rains stop production. Then the weather turns biblical. A flash flood carries away equipment while hail stones descend on the embattled crew. The unit tries to recover but it’s impossible, the dusty valley has turned into a quagmire. Rain has turned the rocks a shade of green, and none of the footage will match up. Rochefort is in constant pain, two slipped discs means he has to take over an hour to dismount his horse. He leaves Spain for a doctor in Paris. First he will be absent for 3 days, then a week, then a month. Then he’s gone.

If the production was D.O.A in its first week, by its second it has been unceremoniously buried 6 feet below by insurance men, completion guarantors and panicking producers. The insurers will not cover the time lost for Rochefort’s absence or the unnatural weather, and one scene sees a room of producers argue over the legal definition of “˜An Act of God’. The crew attempt to continue without their Quixote but another location shoot is ruined by a horse missing its cue in front of an audience of principal investors. Gilliam still has enough energy to laugh it off. The producers attempt to fire the first assistant director, but if he goes, Gilliam will threaten to walk. Then the first assistant walks anyway. With Rochefort missing indefinitely and as a legally termed “essential component” the film cannot continue without him. The entire movie needs to be reinsured, and everything falls apart.

It’s comedic in its excessiveness but La Mancha is better as tragedy, and it’s hard exiting La Mancha to a world where The Man who Killed… doesn’t exist. The movie is broken down and boxed up. Parts of it will be sold on eBay. Reality has beaten the artist, and it hurts. With front row seats to the films fallout, La Mancha feels exploitative. But Gilliam doesn’t remove his microphone, and the cameras keep filming.

Gilliam is not a realist, but it’s more important that he tried. He of course is the man who kills Quixote – over ambitious and under-resourced, he brings a fantasy too fragile into the world to ever really exist, yet La Mancha has an appreciation that such a filmmaker takes the risk – it’s clear that it’s better to have loved and lost than to never have loved at all. It would be easy to recognise that The Man who Killed Don Quixote was mission impossible, but what if it had worked?