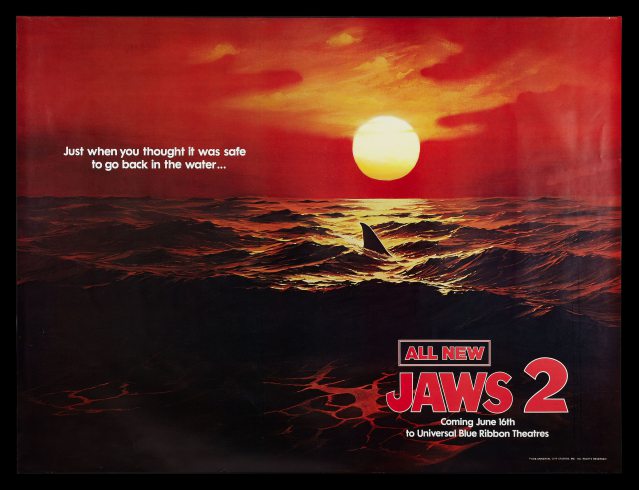

Since the conception of cinema, film posters have, in some cases, become just as memorable as the very films they were made for. For example, who could forget one of the most memorable film posters of all time, Roger Kastel’s creation for Jaws in 1975. Never before has a poster revealed so much about a film, yet at the same time evoked a fear in prospective audiences before they have even entered the cinema. But what of the sequel? By no means a brilliant film, but the poster was pretty cool – thus proving the point that sometimes, the art of a poster goes beyond the quality of the film, and in no other genre is this more evident than in the B Movie.

So what is a B movie? What is now synonymous with trash, exploitation and underground cinema first began in the 1930’s as a way for US studios to maximize usage of their facilities such as sets and equipment, as well as staff and breaking in new talent. It was also a way for cinemas to fill slots in their schedule – quantity over quality assured bums on seats. These were “˜cheap’ movies, made quickly for ravenous audiences in a country that was just waking up to cinema, where nobody had a TV and an afternoon at the pictures was the place to be. The major studios and their expensive productions soon cottoned onto the profitability of cheaper fayre, and started introducing their own “˜B’ pictures to complement their headlining “˜A’ films.

Furthermore, high profile A pictures were only made available if cinemas (or “˜theaters’) hired the B movie to go with it, often at a flat fee instead of the usual box office split. So, if a venue wanted to screen Tom Thumb, they’d have to add the classic Wizard of Oz to the bill, and who would complain about that? Despite being twenty years older, audiences would still come out for it. The result: the studio would see a bigger profit, and more scheduling time dedicated to their product, thereby elbowing out any space for the other studios or independents to push theirs. And thus the A and B movie system came to be – a way of programming features to ensnare wider audiences and heat up the competition between the major studios and the independents. By the time the 60’s came along, many B movies, unrestrained by meddling studio execs and movie stars, had become adept at running wild with their ideas, creating unrestrained works that were either fantastic, violent or gruesome, but always unapologetically tinged with the political. Sometimes, many B movies went on to become classics, with their more expensive A counterparts fading into history – the films of Roger Corman and William Castle being good examples.

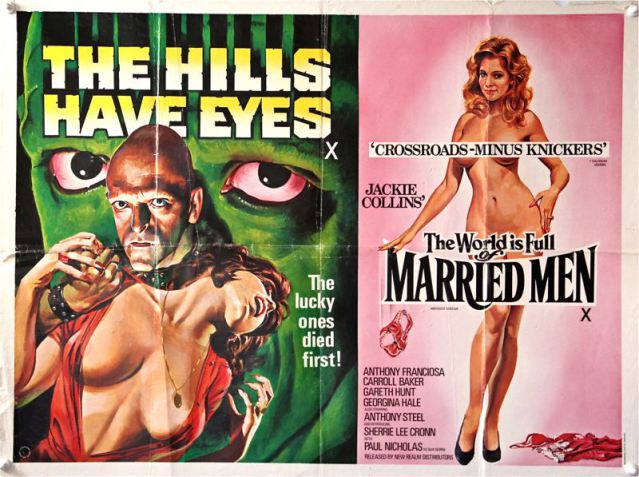

The B’s had now come into their own, no longer in the shadow of the A pictures, and began commanding their own tickets. The B Movie soon became understood as being a film of less than 80 minutes, or a midnight movie, or a film of dubious content. What didn’t change, however, was the pairing of films to fill seats and schedules, which, when you look at the bizarre posters that resulted, makes you wonder which was the A and which was the B, or if the pairing was simply “˜BB’.

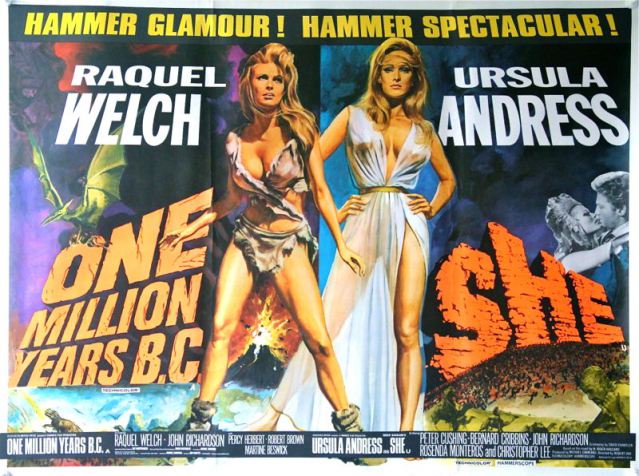

Then there was the practice of the “Double Bill”, which had been present in cinema since the 1940’s with the proliferation of the studio technique called Block Booking, thus allowing studios to sell groups of B movies, rather than just one film. Despite being deemed an illegal practice in 1948, its brief tenure within the studio system had remained long enough for the notion of the double bill to prevail and remain in cinemas well into the eighties. The UK’s very own Hammer were very adept at this. Yet how did cinemas establish what films they were to pair together? Was it through genre, particular actors or actresses, or simply a contradictory bringing together of two films of no relation at all?

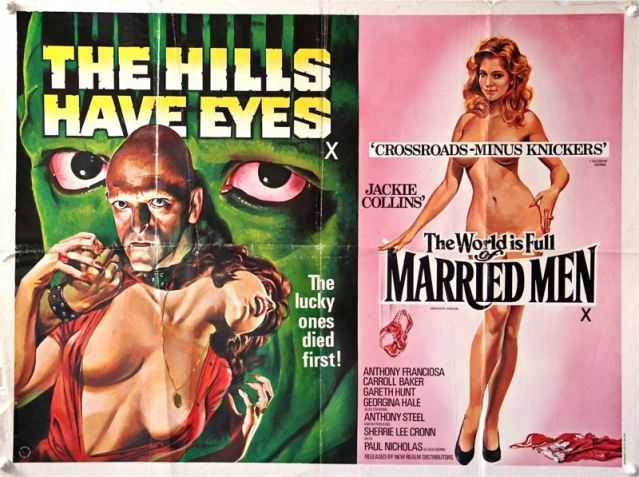

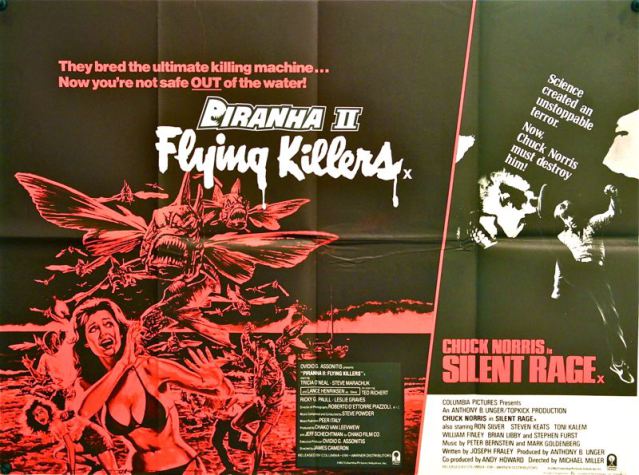

Usually (as can be seen in the posters above), marketing such double bills often led to the posters being used sharing particular visual traits. For example, considering Star Wars 1 & 2 are obviously sequels, the posters consist of a simple split design, whereas She and One Million Years B.C, with their female led lead roles, decide to place both Ursula Andress and Raquel Welch respectively as the focal point of the poster, placing them both at the poster’s very centre.

With the rise in popularity of B and exploitation movies during the eighties, there became a notable difference in how the posters for double bills began to be designed. B movies were almost a novel and somewhat humorous “˜little brother’ to their more illustrious A movie siblings, residing in the bracket of cinema deemed niche. Sometimes, even, they could be reversed.

With A and B films yo-yoing from profitable to flop in equal measure, the pairing of films alongside one another soon became a test of pot luck. As you can see in the aforementioned poster, if horror wasn’t your thing, well ‘Crossroads minus knickers’ might be! So long as you bought a ticket, the distributor just didn’t care.

The combination of A and B movies in contemporary cinematic culture has undoubtedly faded since the eighties. With the abundance of trilogies apparent in film nowadays, the demand for such double bills has waned, with people instead craving for trilogies to be shown in one sitting. There are also fewer cinemas and more movies, so filling schedules is not the priority of yore. However, there is reason to suggest that the phenomenon of the double bill may once more reappear. Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez released as recently as 2007 two films designed to be shown together under the moniker of Grindhouse, a term used to describe B movies from the 70’s and 80’s. Both Planet Terror and Death Proof were thus designed with B movies specifically in mind – the concept of the double feature was being rejuvenated. In the spirit of double feature programming, the two films even had exploitation-esque film trailers slotted in the break. And as if things couldn’t get any more meta, two of them (Robert Rodriguez’s Machete and Jason Eisener’s Hobo With A Shotgun) went on to become films in their own right. One that sadly did not, was Rob Zombie’s Werewolf Women of the SS.

With FilmDoo’s timely launching of a poster competition and some excellent prizes to boot, maybe the above throwbacks can inspire you to create a B movie-esque poster of not one, but two of your favourite films paired in an imaginary Double Bill? You can enter here. So what are you waiting for? Get designing!