By David Pountain

Dir: Lee Chang-dong

Dodging the patronising pitfalls common to disability drama and wrenching the “˜unconventional romance’ trope from the jaws of rom-com cutesiness, Lee Chang-dong’s startlingly provocative Oasis is a film that skilfully does justice to its heavy narrative. At times the film can make for monstrously uncomfortable viewing but it’s handled with such sensitivity and insight that Oasis doesn’t just demand our attention but earns it. It’s a film that encourages self-assessment and prompts us to question our assumptions. It asks us to empathise with people we’d rather avoid and see ourselves in people we may have considered incomprehensible. It’s a type of film that will always be needed. Both courageously forthright and considerately restrained, Lee takes two of society’s misfits and puts them together to create a self-contained reality where both individuals can finally feel like complete people.

Oasis engages profoundly through its two fascinatingly drawn leads. Hong Jong-du (Sol Kyung-gu) has just finished serving three years in prison for a hit-and-run accident. Viewed as an irritating burden by his family, this juvenile 29-year-old alienates everyone he crosses paths with, despite his frequently good intentions. The socially illiterate Jong-du can be short-sighted in his actions and shows little awareness of how he comes across to others but his despondency and insecurity are evident in his habit of giggling evasively in embarrassing and unfortunate situations. His tendency to misjudge social circumstances is made painfully clear when one of the first things he does upon release from prison is visit the family of the man killed in the hit-and-run, dropping off a fruit basket. It’s there that he meets the cerebral palsy-stricken Gong-ju (Moon So-ri).

Like Jong-du, Gong-ju “˜s relatives prefer to keep their distance from her. She receives the occasional visit from her family or her carer but she is largely neglected and occasionally exploited. It doesn’t seem to occur to anyone that Gong-ju is a woman aware of her surroundings and with thoughts and desires worth taking seriously. Jong-du, who quickly takes a liking to her, proves to be the exception but even he goes about trying to get to know her in a horrifically wrong way. The first time he visits her alone, he attempts to rape her until she passes out. After Jong-du runs away in fear and shame, Gong-ju decides to give him a call regardless.

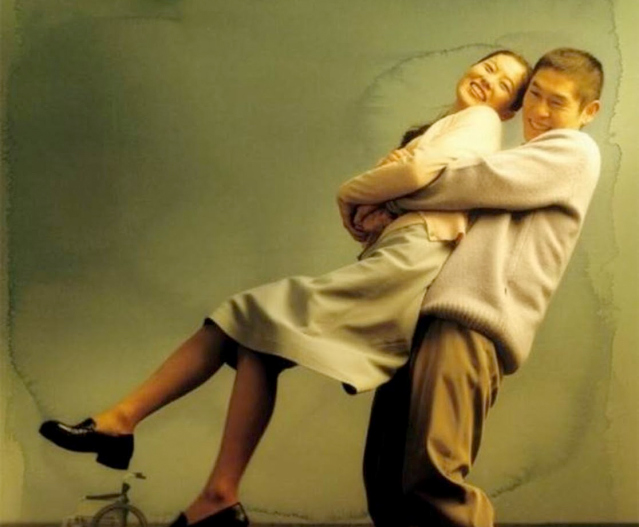

From here, the two quickly strike up a friendship that’s mutually comforting. In the context of this relationship, Jong-du is no longer the awkward pest who always does the wrong thing but a charming entertainer. Gong-ju, meanwhile, is no longer merely an upsetting and burdensome presence but someone appreciated for their humour and compassion. Her condition still makes it difficult for Gong-ju to clarify her thoughts but, in the film’s excursions into the fantasies of her imagination, her feelings are warmly acted out. In her introductory scene, the beam of light caused by a hand mirror is splendidly presented as a dove flying around her room and then, once the mirror breaks so that only fragments remain, shown as a swarm of butterflies made of light. In her scenes with Jong-du, she often imagines herself unhindered by cerebral palsy and in a more explicitly romantic relationship. These visions beautifully illustrate the emotional core of their time together, translating Gong-ju “˜s feelings into a more conventional context to demonstrate their familiarity.

The two lead actors tackle their challenging roles brilliantly. Sol Kyung-gu is poignantly restless and oblivious as the destructively naí¯ve Jong-du. Moon So-ri is often distressingly intense but her emotional nuances are still visible through Gong-ju’s severe impediment. There’s a touching continuity between Gong-ju’s real life manner and her behaviour within her fantasies as a woman free of cerebral palsy, emphasising the individual human behind the condition. Lee Chang-dong uses the city as a vividly expressive backdrop, reflecting the loneliness of his characters by creating an unsympathetic, impatient environment with a barely concealed stigma against Gong-ju’s disorder. That’s not to say, however, that the director doesn’t also use the landscape for romantic ends. One cautiously uplifting scene set in a traffic jam, for instance, sees the honking of frustrated motorists serve as triumphant accompaniment to the central relationship.

Oasis doesn’t clarify just how much of its content the viewer is supposed to approve of. You could argue that Jong-du and Gong-ju’s relationship is ill-advised for a number of reasons, especially given its shocking start and the film’s devastating climax. Still, it’s impossible to deny the sincerity of their affections, and this is what Lee is asking us to recognise above all else. The film certainly puts you through the wringer but it’s a necessary process for revealing love, lust and injustice in their more obscure forms.

You can watch Oasis at FilmDoo today (UK & Ireland only)

One thought on “ASIA: FILM REVIEW: OASIS (2002, SOUTH KOREA)”