Like many countries, Italy has a complex and long history of women’s struggles for equality. Certain rights, however, came much later than other Western societies, such as the laws legalizing divorce (1970) and for gender equality within marriages (1975). Since the 1960s, a time that marked the beginning of feminist movements and women’s sexual liberation, both literature and film have increasingly sought to portray the intricate struggles of women living in a country with strong patriarchal traditions. It is worth noting that only one of the following films has a female director and one other was an adaptation of a female-authored play production.

Much like Hollywood, this discrepancy speaks to the unfortunate lack of gender diversity in the Italian film industry. This does not, however, mean there is a lack of on-screen female representation and struggles, especially since much of Italian cinema is acknowledged for its commitment to social issues deeply rooted in Italian history.

In chronological order, here are a few films most noteworthy for their female representation and portrayal of gender relations.

1. Seduced and Abandoned (Sedotta e abbandonata), 1964

Pietro Germi is one of the leading filmmakers of the post WWII commedia all’italiana genre (Comedy Italian Style), most famously known for his dark comedy Divorce Italian Style, 1961. Using a similar backdrop and motifs as his previous film, Seduced is another exemplary representation of how Italian women, especially in the south, struggled to escape the patriarchal power behind traditional conceptions of family and gender roles. The film follows a Sicilian family whose daughter Agnese is pursued and impregnated by her sister’s fiancé, leaving their second daughter to be set up with an arranged marriage. Germi’s film is a comically satirical depiction of women as social and cultural currency, critiquing the way in which traditional southern society cared more about family honor than a woman’s right over her own body and sexuality.

2. Juliet of the Spirits (Giulietta degli spiriti), 1965

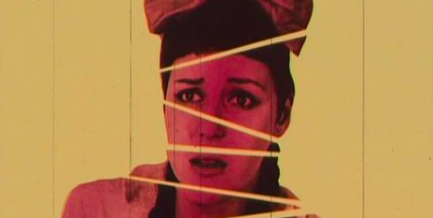

Another classic for any fan of Italian cinema is Federico Fellini’s first color film, Juliet of the Spirits, featuring and named after his wife Giulietta Masina. Like many auteur and art house films, especially those from Italian filmmakers in their prime during the ’60s, critics remain on both ends of the spectrum regarding the film’s ideologies and underlying themes. This film is a unique one in Fellini’s oeuvre because it undertakes a female point of view; however, many critics have found this perspective tainted by Fellini’s own reflections and attitudes.

The bulk of the narrative revolves around Giuletta’s journey toward self-discovery prompted by her husband’s infidelity and her time spent with a promiscuous neighbor, Suzy. The film materializes as a collage of fantastical memories and experiences woven together with Giuletta’s weighty contemplation about female experience. Masina’s childlike and whimsical personality is once more complicated (see also Fellini’s La strada, 1954) by deeper emotional discord, but Juliet is exceptional for its expression of the way in which Italian women in the 1960s were beginning to discover and question their needs and forms of freedom.

3. Respiro, 2002

Emanuele Crialese currently has a short filmography, but all of his films have strong hearts and a large focus on social concerns such as immigration and discrimination (see also Golden Door/Nuovomondo, 2006, and Dry Land/Terraferma, 2011). Having studied in New York, his film style is also appealing to both American and Italian audiences. Respiro, meaning “breath,” beautifully describes the life and struggles of Grazia, a woman, mother, and wife with a bipolar personality. Society treats her as if she has a mental illness, but the film’s setting on Lampedusa (along the Mediterranean sea) instead highlights the relationship between woman/mother and nature, offering a bittersweet yet joyful image of a woman’s innate unpredictability and search for freedom outside of societal standards.

4. Remember Me, My Love (Ricordati di me), 2003

Gabriele Muccino’s family drama revolves around the hidden desires, struggles, and interpersonal relations of a middle class family. At first glance, the film offers a stereotypical narrative of family conflict, but its ambiguous undertones are a constant reminder that perfect families do not exist, and perhaps it is in this imperfection that each member finds space to explore their freedom.

Carlo hopes to leave his mundane office job to become a writer, while his wife, a schoolteacher, likewise dreams of becoming an actress. Their daughter Valentina is quite literally the star of the family; she aggressively seeks fame as a velina, a type of modern showgirl who displays her body and sexuality on television talk shows as spectacle. Both Valentina’s and her mother’s dreams of performing on-screen/on-stage expose the contradictory effect of mass media on women, especially for a country in which television has a long-standing history of censorship and media control. Valentina is a reminder to viewers that women have the right to use their bodies as they choose, but that we should also never forget how much of our (and especially young women’s) desires and choices are dictated by mass media and commercial beauty.

5. We Want Roses Too (Ci vogliamo anche le rose), 2007

Alina Marazzi has won several Italian and international awards for her social documentaries, especially for her 2002 biographical piece For One More Hour With You (Un’ora solo ti vorrei) in which she details her mother’s life through photos, home recordings and diary readings. We Want Roses Too is likewise representative of Marazzi’s unique exploration of cinema through visual media and intermediality, and of her commitment to portraying female subjectivity.

This documentary is a mixture of real diaries, photos, videos, magazines, and advertisements of women during the ’60s and ’70s, the years corresponding to the onset of Italy’s women’s movements. Marazzi also utilized carefully chosen actors and experimental video sequences when best needed in order to portray sentiments of some of the diary entries, especially those dealing with one young woman’s first experiences with her sexuality and abortion. We Want Roses Too is undeniably heartbreaking, but it is also an empowering and hopeful documentary recounting the real experiences of women during a time of radical social transformation.

6. The Ladies Get Their Say (Due partite), 2009

The most contemporary piece on this list is most provocative for its structure and intergenerational narrative. Directed by Enzo Monteleone, the film is actually based on a theatrical work by Cristina Comencini, the daughter of filmmaker Luigi Comencini and known for her work on women’s representation. The film is split into two narratives following two generations of women, thus the Italian title that translates to “two games” or “two [ideological/political] parties.”

The film details a group of women in the 1960s as they spend an afternoon together playing cards and discussing their views and female experiences, which is then paralleled with the present time in which the same women’s daughters reflect on their own friendships and experiences. Monteleone and Comencini’s work is extraordinary for its depiction of female friendship as well as the generational differences between second and third-wave feminism.

Find more Italian cinema on FilmDoo here.

Watch Now on FilmDoo:

(UK & Ireland only)

Juliet of the Spirits is one of my favorites Fellini’s films!