Violent works of shock cinema that seek to cynically appeal to the sadistic (or is that masochistic?) urges of your average gore hound are a dime a dozen, but perhaps no filmmaker has so artfully owned their fetishistic tendencies as the notorious Takashi Miike, whose best films often dive so unreservedly into depravity that they become studies of the very psyches they embody.

Not generally one for big expository scenes, Miike’s films frequently operate by a dream-like, even intuitive logic that suggests Freudian ruminations beneath stylistic surfaces that range from the deceptively placid to the technically dazzling. While the director has almost certainly shot his fair share of scenes that are merely violent for the sake of violence or weird for the sake of weirdness (and, yes, that can be perfectly entertaining too), true Grade-A Miike products tend to serve as richly intriguing and mysterious manifestations of psychosexual and sociocultural concerns.

But when you’re talking about the filmmaker’s output as a whole, it’s important not to get too fixated on the popular narrative of Miike as a master of the bizarre and gruesome because, as his roughly 90-feature strong filmography makes evident, this is a director who defies easy pigeonholing, trying everything from kids films to low key youth dramas to yakuza thrillers to remakes of classic samurai flicks. Not everything he puts out is particularly good (some of it, dare I say, is downright awful) but the incredible volume and variety of the prolific filmmaker’s oeuvre suggests an artist more versatile and unpredictable than his most (in)famous work would imply.

Of course, a side effect of this overwhelming volume of output is that no Top 10 can ever truly represent the taste of every hardcore Miike fan. Some real sacrifices were made to narrow down the selections of this list (particularly honourable mentions go to Happiness of the Katakuris and Dead or Alive 2: Birds) but the ten that did make the cut range from fan favourites and cult classics to even a few underrated gems worthy of more attention.

10. Lesson of Evil (2012)

For a film that climaxes in so unabashedly bloody and pessimistic a manner as Lesson of Evil, it’s easy to forget just how gradually all of the elements leading up to the extended finale fall into place. For much of its runtime, Lesson of Evil is a slow-burning observation of a particularly tense and secretive high school environment – from the conspiring, disillusioned teachers to the troubled and rebellious teens – amounting to a mysterious collage of deceit, corruption, hypocrisy and ethical compromise. By taking the time to expose the personal and systemic vulnerabilities of his characters and his setting, Miike allows us to see the cold cunning by which the charming, handsome teacher Hasumi is able to manipulate those around him.

Though the film as a whole has something of a circular structure based around questions on the nature and origins of evil, the more engaging subtext that runs through the feature is one of crushed dreams and wasted potential. This underlying theme is expressed more subtly through the lives of the broken and cynical parents and teachers, but it is the students who truly bear the brunt of the film’s nihilistic philosophy in the film’s horrifying second half. Speaking of which, while the film’s concluding school massacre sees Miike venturing into territory already heavily explored by many an exploitation flick, it’s hard not to be swept up in the desperate, claustrophobic panic of this unrestrained bloodbath as the director mercilessly and systematically brings each of the film’s many narrative strands to the same sad end.

9. Fudoh: The New Generation (1996)

It’s about fifteen minutes into Fudoh: The New Generation that the film truly announces itself as a mosh pit-ready rock concert of a picture that’s intense and exhilarating enough to elicit vicarious nosebleeds in its audience. That industrial metal soundtrack that comes in with the film’s title card kicks the yakuza drama up a whole other gear, signalling the day where a long festering vengeance finally explodes with literal gallons of blood. From here, we are witness to a series of brutal purges against the older generation, flawlessly executed by Riki Fudoh and his young gang. This isn’t so much a portrayal of the casual cruelty of children – à la certain scenes of Miike’s Visitor Q or Young Thugs: Innocent Blood – but rather the righteous anger of youth. The violent and comical retribution that takes up much of the film’s first half is both utterly tasteless and impossible to resist.

The film’s second half can’t hope to sustain the momentum of the first (though they could certainly have afforded to drop the sex scene, which feels out of nowhere even by this freewheeling film’s standards) but it’s entertaining nonetheless, especially whenever the feature turns into the trippy nightmare it had long threatened to be, with the kids, in turn, facing some fatal retribution from the adults. Overall, while Fudoh may not resonate as strongly as some of Miike’s later works, it’s a refreshing, vibrant and restlessly imaginative creation with its own unique energy far removed from the Scorsese and Tarantino knock-offs that populated gangster cinema at the time.

8. Deadly Outlaw: Rekka (2002)

To a large extent, Deadly Outlaw: Rekka is just one more loopy yakuza thriller from a director who’d already made a career’s worth of films like this. Yet if there’s one thing that puts this entry on the list ahead of, say, 1999’s Dead or Alive, 2001’s Agitator or even the aforementioned Fudoh, it is the endearing balance it strikes between its comical eccentricities and its bromantic emotional core.

The intense, intimidatingly built Riki Takeuchi is faultlessly cast as the uncompromising, child-like yet principled Kunisada. The gangster’s vengeful, absurdly driven nature lends itself perfectly to the head-banging silliness of the film’s many over-the-top action scenes, mostly set to the bombastic Zeppelin-esque guitar stylings of the Flower Travellin’ Band. But whenever the drama settles into something a little lower key, we’re rewarded with affecting displays of brotherhood, like fellow yakuza Eiichi helping Kunisada style his hair before they sit down for dinner.

What was once merely appealingly goofy also becomes touching and tragic, as Kunisada’s anger at the death of a fatherly crime boss is ruthlessly manipulated in a larger chess game for power, eventually leaving just Kunisada and Eiichi as two final renegades, unwilling to die, run away or sell out. Rest assured, the film’s climactic retribution is as deliriously funny, strange and explosive a finale as you could hope for, but the affection that Miike takes the time to show for his central duo keeps us just that little bit more invested in the madness.

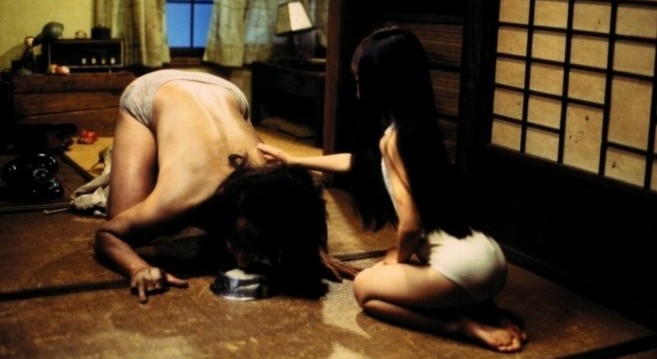

7. Visitor Q (2001)

Visitor Q, one of Miike’s most divisive, emotionally complex works, opens with some on-screen text that reads like a dark parody of a dating show question: “Have you ever done it with your dad?” Over the next unbelievably long 12 minutes, the film proceeds to boldly follow through on exactly what the introductory question promises, capturing the depravity with uncomfortable intimacy. It’s a fittingly repellent-yet-intriguing opening to a film that makes a disturbing and perverse sitcom out of the nuclear family in order to scrutinise our almost universal fascination with the ugliness and catastrophes of other people’s lives. In this scene and others, Miike creates subtle humanity in atrocious spectacle by asking us to reflect on our own voyeuristic urges.

Kiyoshi, the father of the cartoonishly screwed up Yamazaki family, understands misery’s role as a goldmine in the entertainment industry, hoping to exploit his son’s bullying problem by packaging it in documentary form. But this desperate, spineless man is himself the subject of the audience’s shocked and pitiful gaze, with his sexual insecurity even leading him to partake in an ingeniously funny necrophilia sequence.

It’s telling, however, that for all the psychosexual imagery that parades through Visitor Q, the film’s most abundant bodily fluid is breast milk, which the once broken, downtrodden mother of the family secretes with orgasmic and liberated joy. Beneath all of the geek show pageantry lies a sincere desire in each character to feel fulfilled, and Miike, in his own twisted way, suggests that family is the key. It’s a similar conclusion to the one that Miike comes to in the gimmicky but enjoyable Happiness of the Katakuris of the same year, but whereas that film saw its titular family stick together in the face of absurd outside threats, in Visitor Q the characters are drawn together by horrors of their own making, suggesting that a happy family is one that creates a harmony in its sickness.

6. 13 Assassins (2010)

13 Assassins is not one of its director’s most adventurous or iconoclastic creations, but rather it is the work of a more mature, confident craftsman ready to play things relatively straight, albeit with results that are still fairly brutal and insane by the standards of most filmmakers. Getting some of its more grotesque elements out of the way in the first act (most notably in its haunting imagery of a woman with severed limbs and a severed tongue), the film progresses primarily as a tensely constructed tale of duelling strategic intellects, backing up some dazzling spectacles of violence with sharp philosophical and political insights.

Adding a layer of moral complexity to the proceedings is the implication that the corrupt lord Matsudaira Naritsugu is a worthy target of the titular killers not so much for the irredeemable acts he has committed than for the destructive acts he could commit in the future when he presumably rises through the ranks. But it is really the principled nature of Naritsugu’s chief protector Hanbei – a sympathetic samurai whose sense of duty and order drives him to knowingly serve a monster – that grants vital emotional resonance to many of the film’s best scenes.

Yet, even without these intriguing nuances in character and motive, the film’s stunning final fight would still be among the most engrossing action spectacles of the decade. Taking up almost the entire second half of the film’s run time, the climactic face-off between the assassins and Naritsugu’s forces is a veritable funhouse of tactical killing that eventually descends into grizzly, muddy disorder. It’s a delirious, anarchic and suitably bittersweet conclusion to a film where the core question of the narrative is never “Who will live and who will die?” but more accurately, “Who will die for the right reasons?”

5. Young Thugs: Nostalgia (1998)

As the black and white footage in the opening montage of Young Thugs: Nostalgia would indicate, the ‘nostalgia’ of Miike’s often overlooked bittersweet tale of the end of childhood and the death of the ’60s seems in part to be one for classic cinema. Though this is made even more apparent in the deployment of Ennio Morricone’s score from For a Few Dollars More to accompany clashes between the perpetually bloody-faced and battered Riichi and a rival gang of children, this colourful, comical, poignant and calmly paced depiction of youth could perhaps also be regarded as a scrappy descendent of Yasujiro Ozu’s classic childhood dramas like 1959’s Good Morning.

All that being said, if you have any doubts that this is still a Takashi Miike film to the core, just wait for the scene about twenty minutes into the film where a man punishes his adult son by anal penetration with a broom handle. Riichi’s journey into adolescence is also represented by a glorious array of phallic symbols (while the famous Apollo 11 moon-landing comes to represent ‘the harmony and the penis of humanity’, arguably the film’s most ingeniously crude moment comes when Riichi vomits into his recorder, causing a milky fluid to spurt out from the instrument). The film certainly doesn’t shy away from sincerity – take the touching story of Riichi’s friend Kotetsu and his grandmother’s onset of Alzheimer’s – but it’s these crazed, psychological edges to the comedy-drama that make the bravery, endurance, rivalry, sexual confusion and vulnerability of these aimless youngsters all the more compelling.

On a side note, while Nostalgia was made as a prequel to Miike’s uneven but worthwhile 1997 youth drama Young Thugs: Innocent Blood, it is far from necessary that you watch Innocent Blood in order to enjoy the more ambitious, more expansive, better paced Nostalgia, though certain scenes in the latter work take on a more ominous tone once you’ve familiarised yourself with the wild, destructive young adult that Riichi later turns out to be.

4. Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai (2011)

Inexplicably released to cinemas in 3D, anyone who went into Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai hoping for an eye-popping action spectacle comparable to the samurai swordplay of Miike’s last film, 13 Assassins, may have felt a little let down by the patiently paced poverty drama that dominates the film’s run time. Fortunately, it is only when this emotionally devastating remake of Masaki Kobayashi’s 1962 classic tries to be an action film that it pales in comparison to 13 Assassins, significantly improving on Miike’s previous feature in the departments of story, thematic depth and rich, saturated visuals.

The film’s haunting opening third suggests an undermining of popular notions of samurai honour, depicting the young Chijiwa as a shameless huckster who threatens suicide in order to con a wealthy feudal lord out of some charity but whose sword is both literally and figuratively made of wood. The film’s remaining two thirds, however, switch the perspectives to reveal instead the false honour of the elites. As one of Miike’s most carefully composed, sensitive works, the increasing, quiet desperation of Chijiwa’s day-to-day life holds a slowly tightening grip on the viewer, finding arguably its most heartrending image in that of the noble husband and father sucking a yolk off the floor after one of his precious eggs is knocked to the ground.

Such moments serve as powerful illustrations of how desperate circumstances can force principled people to act in undignified ways. From this tragedy comes politically charged anger, directed not just towards the self-righteous beneficiaries of Medieval Japan’s feudal system, but to any sanctimonious authorities whose air of moral superiority is nothing more than an empty suit of armour.

3. Gozu (2003)

The term ‘horror-comedy’ is typically applied to outright comedy films that are merely dressed up in horror film packages but the hypnotic Gozu is that rare example (perhaps even the best example) of a film that truly does erase the line between the two genres. It’s a work of dread-ridden absurdity, paranoid silliness, bizarre cruelty and obfuscation, and irrational but inescapable fears. Protagonist Minami is our baffled conduit in a hallucinatory reality akin to a ghostly limbo. The search for his possibly dead yakuza mentor Ozaki becomes a psychosexual, latently homoerotic odyssey characterised by a perplexing series of tangents, many of them involving milk, for reasons that are yours to interpret.

At face value, Gozu isn’t too different from earlier, similarly weird yakuza flicks from Miike like Dead or Alive or Fudoh: The New Generation. Yet it’s a more patient, resonant feature than that which came before it, going well beyond wacky gimmickry in its impact and internalising the director’s David Lynch influence more profoundly than any other work in his filmography. Its effortlessly ominous series of experiences and interactions – each nonsensical in all the right ways – operates by a consistent inner logic that allows every striking image to burn itself into your subconscious. As for the elusive Ozaki, when Minami finally discovers what happened to his brother in crime, the cognitive dissonance that results is palpable and appropriate enough to tie all of Gozu’s messy madness together, culminating in an astonishing finale that resolves the film’s underlying sexual anxiety in a manner that’s just about freaky enough to work.

2. Ichi the Killer (2001)

Given the exceptional variety and unpredictability of Miike’s output, perhaps it would be meaningless to decorate any one of the director’s works with the title of ‘Definitive Takashi Miike Film’. Still, if one film had to wear that badge, it would likely go to Ichi the Killer, a feature whose every inch is drenched in its creator’s trademark depravity and is all the more profound and compelling for it. With its cast of criminals literally slipping on entrails while strange sexual imagery blends inseparably with the similarly fetishistic violence, it’s as though the whole film is taking place within the psychotic, sadomasochistic mind of the catfish-like Kakihara. From the corrupt detective curious to see if he can yank a man’s arm off with his bare hands, to the drug addict yakuza who gets himself a new face, to the infamous scene of Kakihara cutting off the front part of his own tongue, this is a film that sees the human body pushed to its limits in the name of pleasure.

Yet, while Ichi the Killer certainly earns its reputation as a shock cinema classic, what’s often overlooked is how this hyper-sensory film is ultimately about sensory urges going unfulfilled. It’s a meaningfully excessive creation where the darkest desires of the human psyche are fully externalised to the point of feeling normalised, and hence no longer feel sufficient to a man like Kakihara who’s a junkie to extremes. The artful psycho’s ongoing case of blue balls finds its mocking apex via Ichi himself, an infantile man that Kakihara lustfully assumes to be the ultimate sadist but we see to be nothing more than a blubbering dork made fearful and confused by his own terrible urges. This peculiar clash of two complex and deranged personalities amounts to a fascinating drama of contradicting emotions. It’s a funny, thrilling, skin-crawling, disorienting and tragic work that’s gleefully clever yet menacingly primal.

1. Audition (1999)

“Only when you’re in extreme pain do you understand your own mind.”

In that one line, the mysterious Asami eloquently encapsulates the transcendent purity that Miike finds in extremes. Ichi the Killer and Visitor Q are particularly fine demonstrations of this notion but nowhere in the director’s filmography does it apply better than the final half hour of Audition, possibly the best half hour of any horror film in recent decades, and probably the most excruciating too.

But let’s rewind for a minute. The tamer first half hour of Audition rarely gets much of a mention beyond its intentionally misleading nature – and, yes, one can get much sadistic pleasure from showing this film to unsuspecting friends who initially assume this to be a simple drama about widower Shigeharu looking for new love – but on second viewing, it’s clear that Miike’s ongoing psychosexual concerns are driving the film from the start, loading its dialogue with Freudian implications as the film quietly deconstructs notions of masculinity, loneliness, dependency and the internal narratives we all create for how we want our lives to go.

The nightmare of the film’s climax doesn’t begin all at once but rather we’re slowly immersed into Audition’s dream state via Shigeharu’s increasingly ominous journey to find ‘a nice girl’. Feelings of guilt, insecurity and sexual anxiety build through increasingly haunting imagery and Eihi Shiina’s eerily distant performance as Shigeharu’s mild-mannered, unobtainable object of affection.

By the time we delve into the extended surreal vision that precedes the infamous torture sequence, Miike has never seemed so in control of his craft, yet has also never seemed so unbounded, melding two (unequally) troubled psyches in a mesmerising montage, most horrifying for the way it makes sick art out of the male body. Across a career that’s often seen the director play the cruellest of games with his own audience, never has he felt more ruthless – not just for his viscerally disconcerting depictions of suffering, but for the mental comfort zones he masterfully probes, brutally dissecting our psychological vulnerabilities with an expertise akin to the surgically precise mutilations that Asami inflicts on the physical form.

Watch Now on FilmDoo:

(UK & Ireland only)