By Emma Spencer

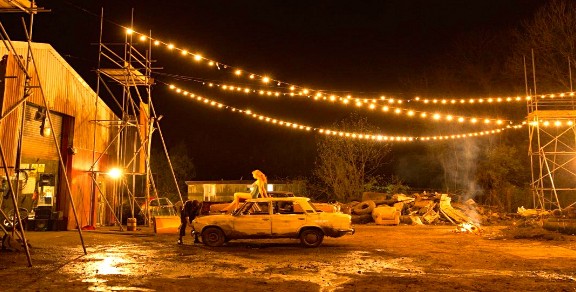

Director: Rob Sanders

Petroleum Spirit is a film so flammable and out of control that the trail of unintentional deaths and chaos make the audience question the difference between what is reality and what is fantasy (“Which way to civilisation?” “I don’t know.”). It’s a film with repeated themes and quotes, somehow tying together the messy bundle of dubious episodes with the unfortunate Errol on his voyage to salvation. The film follows Errol’s rapid fall down the rabbit hole, into the curious happenings of adulthood, facing each unlucky and unworldly event with a curious naivety. The acclaimed commercial writer, Rob Sanders, directs a movie with just as many questions answered as yet to be asked. There’s a deranged but comedic tone to the work, with symbolic notions creating a masterpiece – albeit one that’s not to everyone’s taste. As unpredictable as it is manic, Petroleum Spirit is a film that will capture a viewer’s attention with every frame, in the hopes to resolve the adversity that is the protagonist’s life.

Errol, played deceivingly well by Jarred Thomas, is a hearing impaired teenager who has grown up in isolation with his fearful mother in Lada in the 1980s. From the outset, Errol is portrayed with little hope, and just as little intelligence, yet with a longing to explore the ‘real world’. Displayed as an outcast not only to society but also in his own town, he seeks for some solidarity to prove himself and finally just belong. “You’re not a man” – the words haunt Errol as he winds down the path of adulthood, provoking Errol to rebel against them and attempt to prove his worth.

As a typical sexually-repressed teenage boy, he first seeks solitude in Debra (Ottilie Mackintosh), a one-off customer at the remote petrol station where he works. The cigarette which Debra leaves in her exit later contributes to the climax of Errol’s crumbling life – the final degradation of not only his home, but also his only remaining family. Nancy (Alexandra Weaver), who plays the role of Errol’s mother, is portrayed with an uncanny resemblance to her son’s crush, emphasising the frequently referenced significance of life before Errol. Depicted by the photo on the car bonnet, Nancy loiters in scenes of unruly behaviour – perhaps insinuating that Errol himself is the evil that needs to be eradicated. The cinematography by Martyna Knitter ingeniously disguises the division between past and present, and catalyses the audience’s miscomprehension of actuality. The visual style further removes Errol from the life he knows to be true, creating an outcast demeanour overflowing with confusion, self-doubt and obscurity.

Having stolen the car that inflicted the disability on his mother, evil follows Errol on his road trip through delusion. It would appear that wherever the car goes, peril trails like a ghost of the past, lurking close by, gripping to the sincerity of the protagonist. The array of unpredictable deaths, however, may not be as sporadic as initially thought. With each homicide, Errol is increasingly detached from what he knows to be the normal world, a notion further emphasised by the ever-low battery of his trusty hearing aid, acting as a constant reminder of the divide between Errol’s deluded state and the hard reality of the grown up world.

Albeit through goodwill, Errol destroys each innocent character he meets along his journey to find his father – a man so powerful that he can ‘fix anything’. The fine line between reality and fantasy blurs as he escapes the desolate world of misfortune into the blood and violence of his father. The monster previously depicted, recruits Errol into the criminal underworld, encompassing Errol as a subaltern on the fringes of society. Ivan (Ryan Oliva), the true cuckoo that lay his eggs elsewhere before eating everything including his offspring, is another blunder on Errol’s path to independence. Can Ivan, the father he thought dead, really be the cure for this forgotten, bewildered and confused child?

The steady disconnection that the audience feels with the movie and story line is replicated through Errol’s disconnection to the real world. The Highway Code which Errol obsesses over is the only real set of worthy rules displayed in the film . With each unintentional murder, Errol feels less remorse, in turn contributing to his overall misunderstanding of the so-called real world. A world depicted as a marginalised society, an underworld of no-gooders and corruption.

How can such innocent intentions lead to such disastrous consequences? This is a question that you continuously ask yourself as the story unfolds, until you realise that Errol isn’t about to wake up and brush off the leaves before retelling his story to his deceased mother. Petroleum Spirit is an odyssey burning with a desire for purity, but leaving the viewer’s moral compass spinning, hoping that Errol will finally find redemption. The inadvertent trail of destruction will surely come to an end. But when it does, will the innocence and impulsiveness behind Errol’s previous misdemeanours remain, or will it be more than bad luck that decides the fate of his final victim?

To bring Petroleum Spirit to your region, cast your DooVote here!