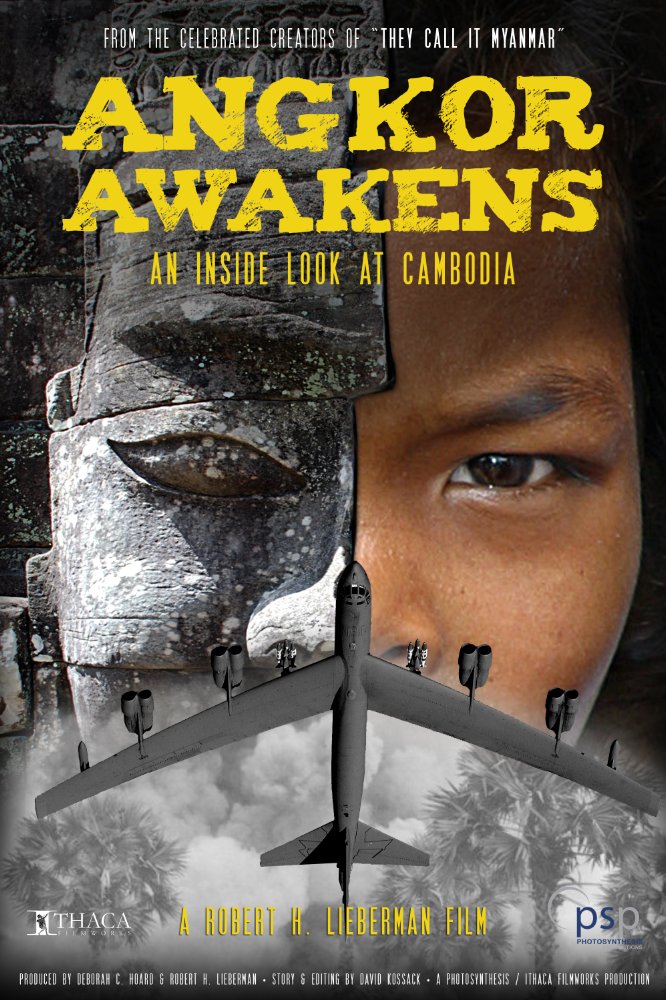

On the 5th May this year,  Robert H. Lieberman’s highly anticipated new documentary Angkor Awakens: A Portrait of Cambodia opens to theatrical release in the US. Lieberman’s previous film They Call It Myanmar, which poignantly captured an interview with Aung San Suu Kyi, was a New York Times Critics’ Pick and hailed by critic Roger Ebert as a 2012 top documentary. Four years in the making, Angkor Awakens follows in the footstep of his celebrated film, with a rare and insightful interview with Hun Sen, the Cambodian prime minister since 1985 – one of the few interviews to ever be given by the authoritarian leader to a foreign journalist.

Robert H. Lieberman’s highly anticipated new documentary Angkor Awakens: A Portrait of Cambodia opens to theatrical release in the US. Lieberman’s previous film They Call It Myanmar, which poignantly captured an interview with Aung San Suu Kyi, was a New York Times Critics’ Pick and hailed by critic Roger Ebert as a 2012 top documentary. Four years in the making, Angkor Awakens follows in the footstep of his celebrated film, with a rare and insightful interview with Hun Sen, the Cambodian prime minister since 1985 – one of the few interviews to ever be given by the authoritarian leader to a foreign journalist.

How did such a beautiful country as Cambodia with its kind and gentle people create one of the largest scale genocides in human history? Shot entirely in English, Angkor Awakens breaks down and traces the history of the rise of Khmer Rouge to power, bringing a fresh level of accessibility and awareness to a new – and often seemingly far removed – generation of the key lessons of this tragedy.

At a full house turnout of the screening of Angkor Awakens at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Thailand in Bangkok in January earlier this year, FilmDoo Co-founder Weerada Sucharitkul speaks with Robert, who shares his motivations for making the film and his journey as a Cornell University physics lecturer turned novelist turned filmmaker. Robert points out to Weerada how every film is like a new startup company.

Robert’s three earlier films They Call It Myanmar, Last Stop Kew Gardens and Green Lights will all be available to watch on FilmDoo from May 5th.

What was your motivation for kicking off this amazing project? How did it come about?

Well I did a film, They Call It Myanmar, with Aung San Suu Kyi and I was in the neighbourhood. Actually, I find Southeast Asia fascinating. I think it’s a place where things are on the move right now. In fact, it’s more interesting than China by far, at least to me. And then there’s my own history as a child of the Holocaust. I know the effects that a genocide has on the next generation and I was interested in exploring it in Cambodia to see what effects, if there are any, still linger. I’m a storyteller and I’m infinitely curious always. Why did I do it? I don’t know, just curiosity. I’m a very curious person. If you sit down next to me on an airplane, I will find out everything about you within an hour, including your sex life.

You mentioned that the film took four years, and that during the third year you were going through some difficulties. How did you keep going? How did you survive that difficult period?

It was already a three-year investment of my life, and to walk away from that was unthinkable. I just felt we had to keep going. I’m really tenacious. I’m like a little dog that grabs onto the cuff of your pants and doesn’t let go. Once I start something, I finish it. I suffer from terminal ADD but I also have this side of me that is compulsive about completing projects. A lot of people are easily distracted; they don’t complete things. They start a hundred projects and complete none. I’m the opposite. I always complete something I start. I’m a novelist and that’s the same thing. I’ve written many books. Some of them didn’t make it – you write a book and you never know. It may not fly. So I’m used to failing, I’m used to rejection and you just keep ploughing on. I mean that’s what artists do and that’s what filmmakers who read your blog are going to do.

I met Otto Preminger, the famous film director, and I asked him this at a screening: How do I get going? How do I start? How do I get the funding? And he said to me, ‘If it’s important enough for you, you will find a way’ – and it really is true. I did a film called Green Lights, which is a comedy. It took ten years to raise the money to do it. So if you’re gonna make films, you’re gonna have to be in it for the long haul. You’re gonna have to believe in what you’re doing, because nobody else will and you’ve gotta convince them.

So how did you get into film?

I’m a novelist. I’ve been a novelist for almost sixty years now. So I’m a storyteller. I’ve written lots of novels and it’s a natural progression to film. I’ve had some books that have done very well – a few hundred thousand copies sold – and some books that didn’t do well but if you reach ten, twenty, fifty thousand people with a book, that’s doing well. With a film, you could reach millions of people.

Also, you’re in the post-literate generation. Film is easy. It’s easy to watch, although when I watch a film, I’m just completely absorbed. I really concentrate on a film. I’m not passive and you don’t wanna sit next to me during a film. When my wife is next to me, I’m sure I annoy her because I’m constantly commenting on the film. And I don’t need popcorn when I watch a movie. I don’t eat. I don’t drink. I watch the movie.

I have a very good test by the way. If you forget you’re watching a movie then it’s good, if it takes you for the ride. That’s true when I write novels too. I wanna grab you by the collar – whether it’s a novel or a movie – and never let go. I wanna take you on a ride and keep the tension going.

Given the current global political climate, what are some of the interesting lessons from Cambodia that you feel really resonate and that we can learn from?

I think history doesn’t exactly repeat itself but the patterns are being repeated. I forgot who said it, that doing something repeatedly and expecting a different outcome is the definition of insanity. We went into Vietnam, we did not understand the culture, we did not speak the language and it was a disaster. Then look what happens: We’ve gone into Afghanistan, we’ve gone into Iraq, Libya, we don’t understand the culture and we Americans are being played. People are running circles around us. The film’s worry is that you can destabilise countries but it’s very hard to put them back together again. The United States, in my opinion, is not solely the cause, but George W Bush invading Iraq was a disaster. There was no reason for it. I was against it from the first and it’s started this cascade of chaos.

And you said the film was opening in May in the US?

May on the East coast in the United States, after mid-May on the West coast and it’ll be in Europe too. Opening theatrically is very tough for a doc. I just had such success, luckily, with the Myanmar film. I worked with a couple of theatre chains and we had such a good turnout that they’re giving me another chance and I hope that we can prove our mettle, get the kind of turnout that we need.

Of course, publicity is everything. I have a theory that making a movie is 25%, and 75% is promotion and distribution. So making the movie, which is horrendous as you know, is only a quarter of the job, or maybe a third. The back end is everything. So you’ve gotta get funding somehow, you’ve gotta get the subject, you’ve gotta make the movie, you have to edit it and then you start the uphill climb but if you don’t believe in it, then you can’t sustain it. You have to believe in it, that it’s somehow worthwhile doing.

So what’s your next project?

I’m working on an animated film, The Nazis, My Father and Me, in Paris [teaser below] with Didier Brunner who’s a five-time Academy Award-winning producer, who did The Triplets of Belleville and The Secret of Kells. Have you ever seen any of his? They’re wonderful. I’m doing a screenplay. I think we’re in the second or third draft, I lost count. And then I wanna do a musical and I’m debating another doc – maybe in Iran if I get in. I’m open.

Lastly, are there any words of wisdom that you can share with any up-and-coming filmmakers?

Interesting thing: At least for me, every film is a new startup company. You start from scratch, really. You’re only as good as your last film and the truth in the matter is that each film is new and you have to reinvent the wheel each time.

I suppose if you’re a starting filmmaker, you just have to start! You have to be brave and you’re not going to get rich. You’re going to be poor probably, especially if you’re young, but the world needs new voices and new insights and I’m at the tail end of my life and you and your readers are at the beginning. I don’t know if I would start all over again. I’ve decided to become a Buddhist because you’re given a second chance, but I’m gonna come back as a musician, not as a filmmaker or a novelist. I actually have the epitaph for my gravestone. You wanna hear it? It used to be, ‘He wrote different books.’ Now it is, ‘He wrote different books and made different movies.’

Angkor Awakens will be showing in US cinemas from May 5th. Find more info here.

Robert’s three earlier films They Call It Myanmar, Last Stop Kew Gardens and Green Lights will all be available to watch on FilmDoo from May 5th.

One thought on “INTERVIEW: ROBERT H. LIEBERMAN TALKS ANGKOR AWAKENS AND HOW TO MAKE IT IN THE FILM INDUSTRY”