The ’60s and ’70s were periods of formal innovation for cinema; particularly that of the Horror genre, with some critics dubbing the seventies to be a period of renaissance (or a ‘Golden Age’) for the genre. Not only was this a period of artistic and intellectual activism, but a period emerging from the social turmoil following Civil Rights movements and the Vietnam War. Such an era induced an unusual change in the representation of the American family in Hollywood cinema. The family, once identified as a positive illustration of a ‘normal’ society, found itself undergoing grievous assault.

Here, FilmDoo will look into the treatment of the family in some of the most prominent and influential Horror films from the 1960s and 1970s.

Psycho (1960)

Psycho represents the genre’s departure from gothic castles and foreign monsters and presents audiences with one of the first indigenous American monsters. From the beginning of the film, the family dominates every character; characters are either repressed by deceased family members or their desperation to start a family leads them to their demise. Sam works to pay off his deceased father’s debt, Marion wishes to dine with Sam in front of her deceased parents’ photograph, and Norman’s identity is dictated by the persona of his deceased mother.

Psycho’s Norman Bates illustrates a monster born from familial tensions and repressed sexual emotions; Norman is an embodiment of the oppressive nature of contemporary American families and their logical conclusions. America is no longer depicted as a prosperous land of the free, but an immoral, repressed and socially corrupt dystopian wasteland.

In the period following the release of Psycho, the family has been perceived as an increasingly dysfunctional unit, one which has become a catalyst for incestuous behaviour, mental and physical abuse, and Oedipal angst – therefore, localising the family home as a place of horror.

Rosemary’s Baby (1968)

Post-Psycho, the American horror film entered an era that oversaw the systematic collapse in both the assurance in, and the promotion of the family and conservative family values. Children, whom were once revered as an epitome of ideological neutrality and innocence, became reconfigured as the new American monster.

Demonic horror films did not attempt to produce an American monster; instead, they continued the long-standing tradition of disowning America’s evils as foreign. At face value, this appears arguably retrogressive, however, these films subvert generic interpretations of foreign evil by proposing that familial tensions are the heart of the possessions and satanic activity. Through the deconstruction and destabilisation of the American family, these films disavow relevant social factors by ascribing familial circumstances to demonic possession or the return of the antichrist. Rosemary’s Baby comments upon the females’ ideologic and predestined role in western patriarchal society; by the end of the film, Rosemary becomes trapped within a darker and parodying ideologic role to which she desires at the start of the film. Ultimately, it is Rosemary’s craving for an ideologized family unit that leads to the inevitable annihilation of contemporary society.

The Exorcist (1973)

Unlike with Rosemary’s Baby, the large majority of critics overlooked The Exorcist’s radical critique of the family, despite its integral role within the diegesis. Beneath the Exorcist’s shroud of supernatural imagery lies familial tensions; these tensions provide the stimulus for Regan’s demonic possession. The narrative intimately follows the story of two families, the Karras and the MacNeil families, both of which are trapped within a state of familial disintegration. Regan misses her absent father while resenting her mother’s involvement with Burke Dennings, a local director, whereas Father Karras is trapped within an uneasy relationship with his dying mother.

Karras suffers from religious doubts. He carries an enormous guilt over his decision to leave his mother in her slum household and his career path taunts him. As a celibate male figure, he carries repressed feelings of resentment, anger and guilt. Both the MacNeil and Karras families exist in a deteriorating America that provides no coherent solutions to familial dilemmas. Although the opening sequence desperately attempts to externalise the monster as a supernatural evil, The Exorcist reveals that the family is in fact the imminent threat. The film also sought to question the role of 1950s traditional family values by illustrating a society in which parents can no longer dominate their children and the offspring rejects parental authority.

The Omen (1976)

The Omen disowns its horror through the externalised demon child: a product of the old world and adopted by the new world American family. The film never attempts to explicitly criticise its familial unit; although the world is ending, the film attempts to affirm traditional family values – it is the demise of good, Christian world we love, and only external evils are at fault. Although the film lends itself to readings illustrating the tensions between childhood and parental resentment, the narrative never allows for these ideas to develop. Damien is clearly depicted as the antichrist; the film evokes a sense of predestination which restrains audiences from drawing parallels between the realms of the demonic and the familial.

Much like The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby, deception within the familial unit generates satanic assault. In The Omen, Robert lies out of compassion for his wife, however, this deception evokes repressed consequences to emerge, which, in turn evokes their self-destruction. Despite externalising the threat, the demonic films of the seventies still succeed in using the family as a means of illustrating institutionalised repression and social turmoil through the familial unit.

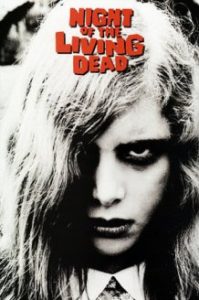

Night of the Living Dead (1968)

The families within Night of the Living Dead are preoccupied with their own world and refuse to unite against a common enemy. In this case, the enemy (the zombies) are an embodiment of repressed paranoia. The family lies at the heart of the narrative; Romero’s cannibalistic zombies are the logical successors to Hitchcock’s winged antagonists in The Birds; both respond to familial and psychological tensions, however, this time the attack is considerably more violent and abhorrent. Ultimately, it is familial ties that evoke unforeseen consequences.

The Last House on the Left (1972)

In The Last House on the Left Craven intends for both the Collingwood and Stillos families to be symbolic of ‘us’. The film establishes both families as opposites, slowly blurring the boundaries that separate them until the audience can no longer find a means of establishing emotional connection to the violence on-screen; this lures spectators into self-disgust and self-awareness. Much like Psycho, the film attempts to corrupt its voyeuristic spectators. By depicting the horrors of violence, the film confronts its audience with the direct implications of the genre’s spectacle and experience; in doing this, Craven constructs a dismal, dystopian world, which encourages spectators to identify the film’s dark associations with the outside world.

The Hills Have Eyes (1977)

Much like Night of the Living Dead and The Last House on the Left, the traditional American family within The Hills Have Eyes must confront their darker counterparts, which in turn unveils repressed violent tendencies lurking beneath the familial exterior. In Hills, the cannibalistic family lurks within the confines of an American nuclear test site. The family exist within a dangerous environment, one that subjects them to a constant threat of annihilation. Despite their conditions, the family sustain themselves on salvaged technologies and cannibalism. Their conditions contrast with that of the Carter family, who are beneficiaries of the American Dream. Jupiter’s family embodies a repressed vengeance against contemporary social structures and ideologies; this becomes evident when the family kills Bob, the patriarchal beneficiary of an economic system that condemns them to starvation and poverty.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre presupposes the malevolent and violent nature of the American family; the slaughterhouse family are losers of the American Dream, a dark embodiment of American ideologies. They represent a familial unit made socially redundant by the rise of contemporary technologies and capitalist industrialism. As a result of their redundancy, the family are forced to live on the margins of civilisation, imbedding within them with anti-capitalist ideologies and a hatred for bourgeois patriarchal structures. Like the zombies of Romero’s Night of the Living Dead, or the cannibal family of Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes, the family embody repressed, violent familial tendencies. Texas Chainsaw actively attempts to reverse and pervert existing definitions of the monster and normality. In this case, normality is illustrated through the permissive group of young teenagers, whereas the monster encapsulates the family unit. The film actively reminds American audiences of their own evil through the creation of an indigenous American monster; one which was born in the heart of a rural American family. Leatherface and his family remind audiences that cannibalism, violence and apocolypticism are the logical conclusion to an exploitational capitalist government and the diminishment family values.

Ultimately, the horror film of the nineteen-sixties and seventies was largely dominated by several recurring motifs, (The Monster as Psychotic or Schizophrenic; The Revenge of Nature; Satanism, Demonic Possession and the Antichrist; The Terrible Child and Cannibalism) all of which are tied together closely by a singular, unifying figure: the family. The family became a catalyst for socio-political criticisms of contemporary social structures and American ideologies; the demonic horror film ascribes demonic possession and the antichrist to the family in order to critique child-parent relationships and the mother’s predetermined role as child-bearer in a patriarchal society, whereas the cannibal horror film envelops itself with a Vietnam-heavy subtext, which suggests that violent tendencies are repressed within the family, and that cannibalism and apocolypticism is the inevitable and logical endpoint to a capitalist economy.

Watch On FilmDoo:

(UK & Ireland only)