Interview translated by Kiradit Sachdev

Watch The Ravine of Goodbye on FilmDoo

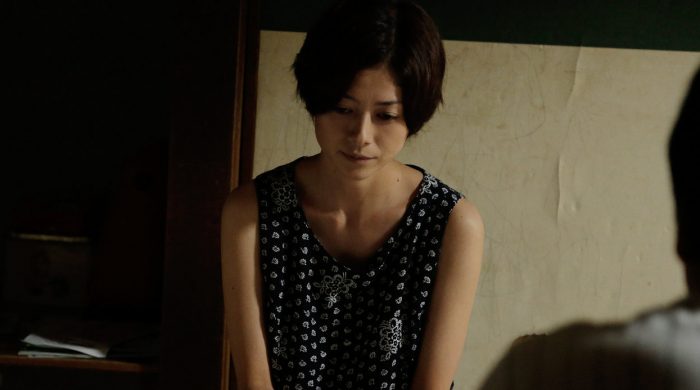

In Tatsushi Ohmori’s The Ravine of Goodbye, two horrific incidents – one still in the headlines, and one from a distant past – serve as prismatic conduits through which we observe the dark, contradictory facets of human nature and modern society. Based on the Japanese 2008 novel Sayonara keikoku by Shûichi Yoshida, the drama begins with a highly publicised child murder case in a small community before delving deeper into the personal history of local couple Ozaki and Kanako to reveal another troubling tale of cruelty, lingering trauma and unshakeable regret.

Speaking to FilmDoo, director Ohmori looks back on his award-winning 2013 film to discuss how this sombre, mysterious and resonant work came to be.

How did you first come across Shûichi Yoshida’s short story and what made you interested in adapting it?

Shuichi Yoshida’s novels are very popular in Japan. I had a desire to make a film out of his novel titled Bad Person. However, this did not happen. Afterwards, when the novel titled The Ravine of Goodbye was published, many directors also desired to make a film out of this novel but luckily I was successful to be the chosen one. Why were the rape victim and the perpetrator living together? I was drawn to that simple theme of the novel.

What were some of the challenges in adapting Shûichi Yoshida’s story into a feature-length film?

The story of the novel wasn’t short. You couldn’t just sum it up. I thought it was appropriate to make a 2-hour film. When adapting a novel into a film, the most important thing that one has to be careful about is that, in the novel, the voice of the heart is written, but, in film, those voices cannot be expressed as words other than by making a script of dialogue, narrations, a diary style or the like. In the film, I try to express things strongly and deeply as words without words, through the expressions of actors, appearance, speech, lines, and scenery. I think this is the richness of the film.

Female lead Kanako is a particularly complex, mysterious character who often displays contradicting desires. Do you feel human beings in general can be very contradictory in their nature?

Of course. Human beings seek consistency in their lives, but it is actually just a way to survive in the framework of the society. Excessive love and unavoidable violence are obstacles in society. However, as living beings, we possess such inclinations. This contradiction holds for humans at all times. It is in this element that drama is born, even for Shakespeare.

Through the story of a murdered child, the film shows us the media’s fixation on tragedy. In your opinion, why are such awful events so fascinating to both the media and the general public?

I think that it is interesting as an exhibit. Humans coexist in contracts to live according to laws and morals in the system of society. And so they live with the feeling of stress. But if you see yourself in a cruel story or in an obscene relationship then you take it as an outlet for your stress and take a strong interest. When we are interested in such circumstances, we need to think about from what perspective we are looking. Then the film will also become more diversified.

Given the film’s sensitive subject matter, was The Ravine of Goodbye met with much controversy in Japan upon release?

“Why do they live together? I do not understand,” there were a lot of such opinions. But because I do not understand, that’s why I am drawn to it. It give me a feeling of the nonsensical. Inarguably, what one thinks in their own head is only an event in their head. In our own lives, people will find things that they do not understand. What do they think when they are faced with such things and what action do they take? I think these are important points.

Are you working on any new projects?

A film titled And Then There Was Light (hi-ka-ri.com) will be released this year. It is a human drama based on the concept of life force, such as that of plants and animals.

Watch The Ravine of Goodbye on FilmDoo

Find more Japanese films here.

Original Japanese Interview:

吉田修一さんの原作短編とはどう出会いましたか?なぜ映画化しようと思いましたか?

吉田修一さんの小説は日本では大変人気があります。僕は彼の小説『悪人』を映画化したいという思いがありましたが、叶いませんでした。その後に出版された『さよなら渓谷』も様々な映画監督が映画化を希望していましたが、運良く僕が監督することが出来ました。この小説のレイプ加害者と被害者が一緒に住んでいるのはなぜか? というシンプルなテーマに惹かれました。

原作短編を長編映画にすることに当たって、どんな挑戦(困難)がありましたか?

この小説に短編という意識はありませんでした。むしろ二時間の映画にするには程よい長さだと思いました。小説を映画にするときに一番気をつけているのは小説では心の声が書いてありますが、映画ではそれをセリフ、ナレーション、日記などにする以外、言葉として表すことができません。映画では俳優の表情、佇まい、セリフの間、風景、など言葉なき言葉としてより強く深く表現できるように心がけています。それが映画の豊かさだと思います。

女性主人公のかなこはとても複雑でミステリアスなキャラクターで、よく矛盾した欲求を見せています。人間は普遍的に矛盾するものだと思いますか?

もちろんです。人間は生きるために整合性を求めますが、それは社会と言う枠の中で生きて行くための方法論にすぎません。過剰な愛やどうしようもない暴力性は社会では邪魔なモノです。しかし私たちは生物としてそのような感情を持ち合わせています。この矛盾は人間にいつの時代でもつきまといます。それがドラマの産まれる瞬間です。シェイクスピアだってそうですよね。

子供の死の事件で媒体は悲劇に対していかに(病的)執拗な報道をするか、この作品で垣間見えています。監督の意見として、なぜこのような悲惨な事件はマスコミや大衆の関心を得ると思いますか?

見せ物として面白いからだと思います。人間は社会という制度の中で法律や道徳に従い生きることを契約して共存しています。そしてそのことのストレスを感じながら生きています。残酷な事件や淫らな女性(男性)関係などにどこか自分を重ねながら、ストレスのはけ口として見ているから強い関心を得るのです。私たちはそのことへの関心を持つときに自分自身がどの視点で見ているのかを考えることが必要です。そうすれば映画ももっと多様化するでしょう。

敏感な内容を扱うこの映画は、日本公開のとき何か議論とか批判がありましたか?

「なぜ一緒に住んでいるのかわからない」という意見が多かったです。でも僕はわからないから描いているわけで、そのことはナンセンスに感じます。自分の頭で考えていることは、当たり前ですが頭の中の出来事です。僕たちは生きている上で、わかるものよりわからないものにであうことの方が多いはずです。

わからないものと出会ったときどのように考えるか、行動をとるか、それが大事だと思います。

いま何か新作を準備していますか?

『光』(AND THEN THERE WAS LIGHT)http://hi-ka-ri.com

という映画が今年公開になります。

植物や動物のような生命力そのものに視点をとった人間ドラマです。

Banner image from i.ytimg.com