What is now referred to as “The Iranian New Wave” is an ongoing movement that has been taking place for about 50 years, throughout many major political and social changes in Iran. It is comprised of three waves. The first and second are separated by the Iranian revolution of 1979, while the second and third are less definitively separated by the early 2000s. Although, at times, the New Wave has been promoted, even funded, by the Iranian government, it historically amplifies alternative voices, and reflects views of the anti-establishment.

The Cinema of Real Life

Often incorporating documentary footage or documentary-esque realism, Iranian New Wave films concern themselves with the problems of real Iranian people, whether those problems are a matter of life and death, as in the films of Bahman Ghobadi, or inter-personal and moral, as in the films of both Asghar Farhadi and Abbas Kiarostami. Iranian New Wave films don’t care about the rich and powerful, and they have no interest in cut-and-dry tales of good and evil. Unmistakably modern, Iranian films revel in moral ambiguity, raw humanity, and everyday life, plumbing the depth of the human experience to find common ground.

Pre-Revolution Iranian Cinema

Film was introduced into Iran in the early 1900s, and by the 1920s, government sponsorship allowed film to be affordably consumed by the masses. With visual art and storytelling both central parts of Iranian culture since as early as 500 BC, Iranians were quick to embrace the new medium.

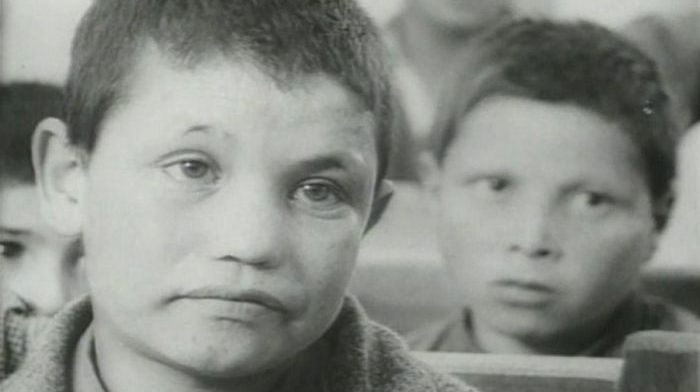

Prior to the Iranian Revolution of 1979, the Iranian government, headed by the Shah, took no issue with the public consumption of Hollywood films and production of Hollywood-style domestic productions, known as Film Farsi, characterized by song and dance numbers, optimism, glamor, decadence, and often, immodesty of women and gratuitous violence. Some filmmakers objected to the mimicry of American cinema in lieu of creating their own national cinematic identity, as well as the superficially rosy depiction of everyday life. They rebelled by creating films about rural Iranian life and everyday struggles, using experimental techniques and symbolism to be subtly critical of the regime. Viewed as Soviet propaganda, many of these films, later known as the First Wave of the Iranian New Wave, were banned.

A good place to start: The Cow (1969), The House is Black (1963), Qeysar (1969)

Post-Revolution Iranian Cinema

Among many other complicated things, Revolutionaries were tired of government corruption, poor living conditions, and a loss of national identity, and sought a return to core religious values in conjunction with greater social justice. After the revolution, they enforced this, at first, through censorship and control, and since film had come to represent vice and excess, the whole industry was basically frozen. That is, until First Wave films began to resurface. The gritty realism and modest representation of Iranian culture appealed to the new leadership, which began heavily sponsoring high-quality films and filmmaking schools.

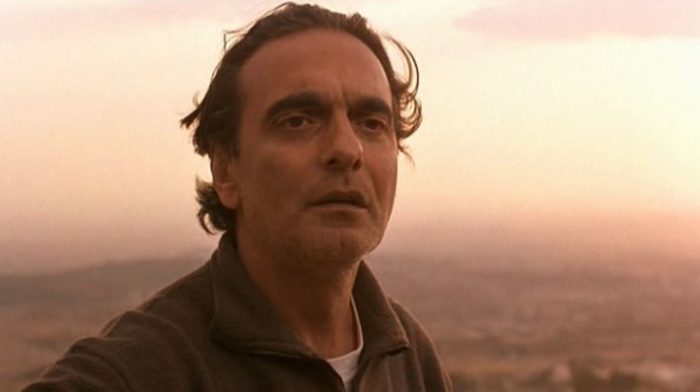

This ignited a renaissance of Iranian cinema, later known as the Second Wave. At first, filmmakers cleverly worked within the confines of the censorship, even inspired by these creative limitations, but as these films began to circulate internationally, filmmakers increasingly split from the new conservative values of the government that created them, reintroducing sexuality and violence, raising doubts about the new government, exposing the horrors of the Iran-Iraq war, or simply getting too existentially weird for the censors to feel comfortable with. By the time the government began to crack down on this new incarnation of subversive filmmakers, it was already too late, and Iranian films were winning prominent awards at international festivals and getting into global circulation.

A good place to start: Taste of Cherry (1997), The White Balloon (1995), Children of Heaven (1997)

Iranian Cinema Today

Today, in the midst of the Third Wave, there is still a prominent film industry in Iran with festivals and film schools in the capital of Tehran and elsewhere, with a higher percentage of female filmmakers than many Western countries, and frequent international collaborations. Iranian filmmakers continue to captivate international audiences. The government is happy to support domestically produced formulaic commercial films, but New Wave filmmakers and minority filmmakers, like those from Iranian Kurdistan, are less reliably allowed to screen. Films are still banned, mostly imports, and the government continues to produce anti-American and anti-Hollywood propaganda, although many Iranians don’t buy into it and continue to consume whatever art and entertainment they like. Today, Iranians can easily get their hands on everything from big budget Hollywood films to other international arthouse films by purchasing easily accessed illegal copies. The huge expense of regulating such activity forces the government to turn the other cheek.

A good place to start: A Separation (2012), Turtles Can Fly (2004), At Five in the Afternoon (2003)