London Feminist Film Festival interview

In this experimental collage-like film, Nina Hoechtl and Julia Wieger explore the diverse, and sometimes unsettling, history of the VBKÖ: The Austrian Association of Women Artists. From progressive beginnings, to a dark sympathising with Nazism during the Second World War, the film questions whether the VBKÖ’s fluctuating past can be worked through. Today, the organisation serves as a space for supporting contemporary queer and feminist agendas; but how can the group’s current members best confront the ‘ghosts’ that lurk in the archive?

FilmDoo talks to the film’s directors, Nina Hoechtl and Julia Wieger, about the film’s inspirations and their thoughts on the organisation’s difficult history.

When did you first become aware of the VBKÖ and what attracted you to its story?

Nina got to know about it through an open call for the Cyber Feminism Past Forward exhibition (curated by the then VBKÖ president Rudolfine Lackner and Evelin Stermitz) in 2007. Julia was invited, along with three other colleagues of hers, by a then VBKÖ board member to use the spaces of the association for a summer residency.

Our paths had not yet crossed then, but we both were immediately intrigued by the association. The VBKÖ had been introduced to us as a historically feminist space, but not a very active one. It was hidden on the 4th floor of a bourgeois representative building close to the opera house in the historic centre of Vienna. At first sight, it seemed to be a place with lots of potential and, since it was one of the first women artists associations in Europe in 1910, it carried a lot of historical weight. It was only later that we found out about its complicated and unsettling past; for example that the 1938 board of the VBKÖ had opted to collaborate with the National Socialist regime.

When we both became members of the board in 2012 it was the first time that we had the chance to really delve into the archive of the VBKÖ. This was also when we founded the working group Secretariat for Ghosts, Archive Politics and Gaps, in order to grapple with its his/herstory/ies through workshops, exhibitions, lectures performances and, now, a film: Hauntings in the Archive!.

What inspired the film’s collage-based style?

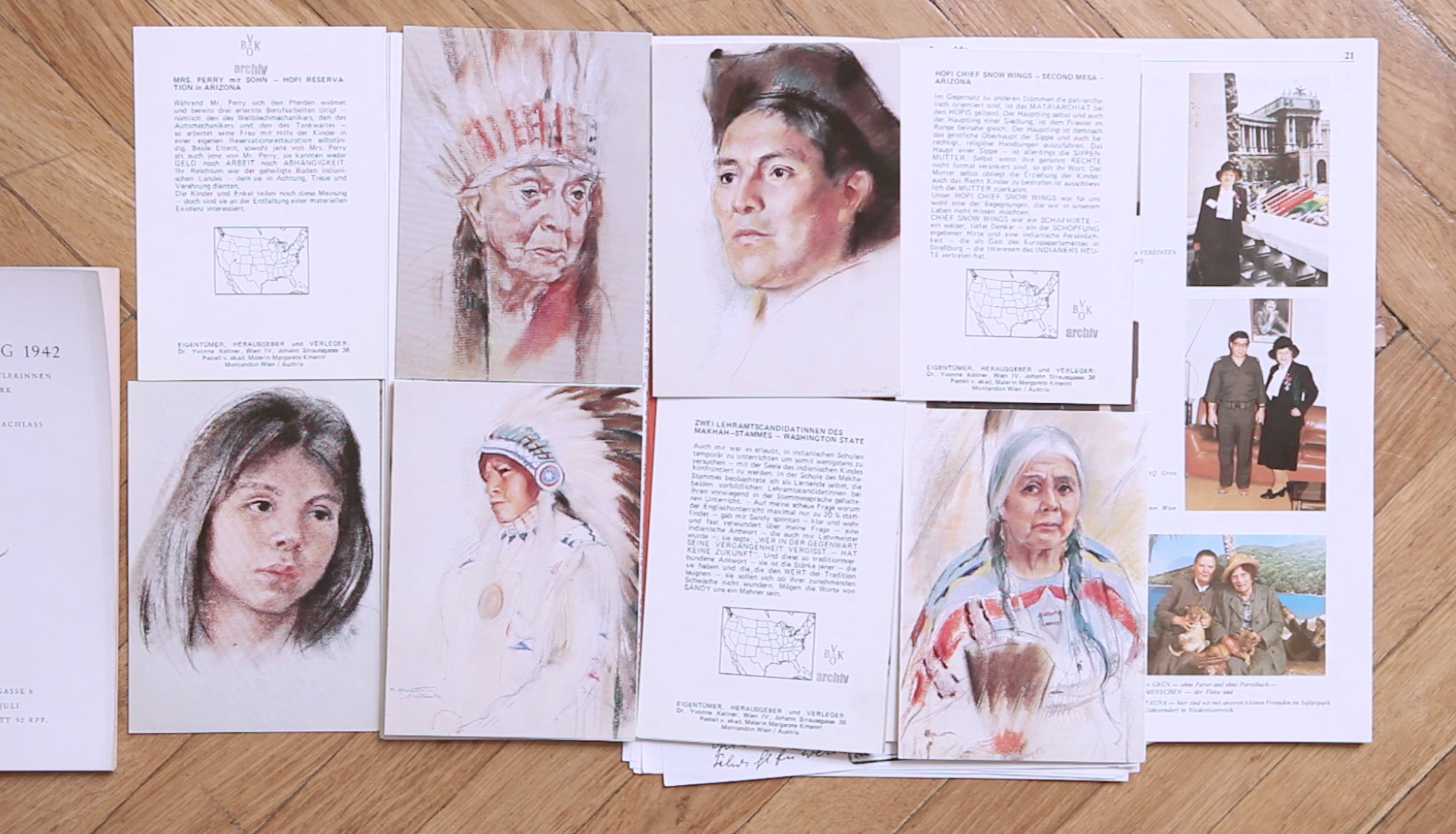

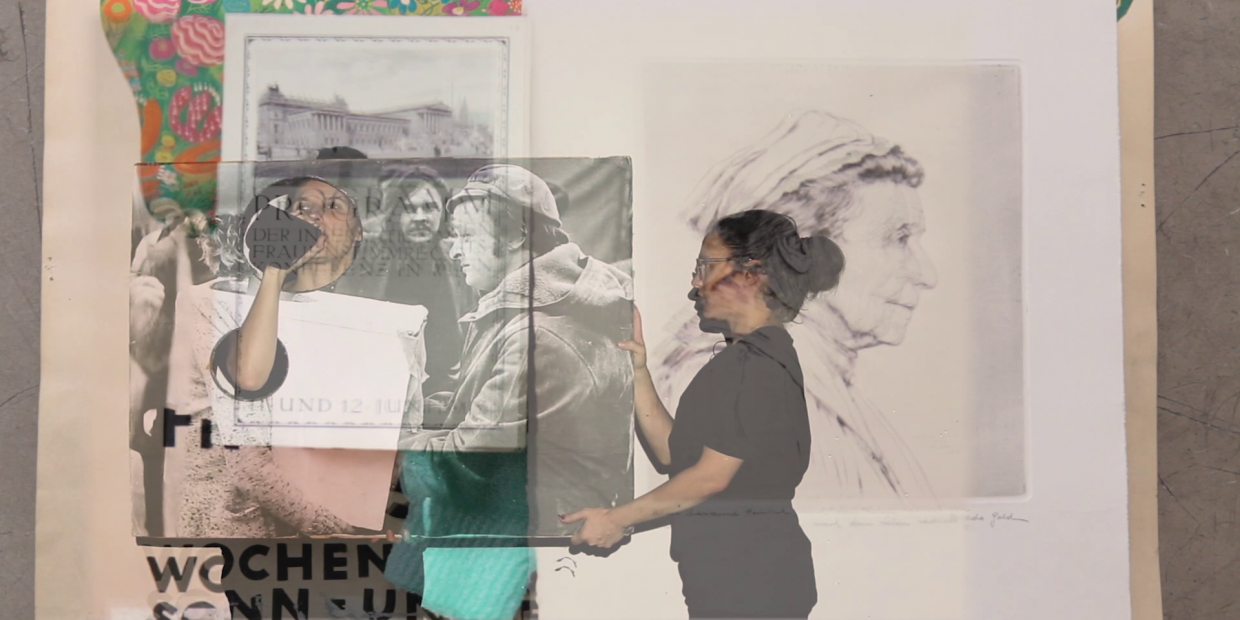

The vast archival materials and their materialities. Confronted by their varied nature we asked ourselves how to deal with them; how to reckon with its gaps and continuities that make ghostly appearances in different guises; and how to write the his/herstory/ies of the present and the future.

Although connected by the association and its space, the materials are from disparate sources and different historical moments. They, in themselves, called for a collage. Through juxtaposing, assembling and superimposing them we conjure up the ghosts of the multiple, complex and politically contradictory incarnations of the VBKÖ.

How do you feel the archival process of discovery impacted your relationship with the VBKÖ?

Our practice intertwines artistic, research and institutional works. They go hand in hand and influence each other. For example, going through the archival materials evinces how an institution threw their twenty-eight years of resisting, empowering and resilient practices overboard in order to meet the requirements of the National Socialist regime, to expel its Jewish members, and to align its program with the ideologies of the Nazi regime. Our research into the VBKÖ archive, the very way we approach and un-/re-learn about the VBKÖ’s century long activities, are very closely tied to their shifting modes of operation, and thus to how we could try to change them.

Through our institutional work at the VBKÖ we seek to make it more intersectional, while attempting to identify and challenge internal blind spots, dynamics of discrimination and exclusion. This is an ever ongoing, difficult and demanding work but we consider that an institution like the VBKÖ can support collective efforts by providing space, resources (as small as they might be), and time for critical reflection and experimentation. As we state inHauntings in the Archive!: ‘We consider the VBKÖ archive to be a site of political confrontation; of action and intervention in the present; of re-projection and re-imagination of the future and to welcome spectres.’

The film refers to Nazi ideology and colonial fantasies as ghosts – what do you mean by this?

As we show in the film, after 1948 one member reproached the association that the ‘evil Nazi spirit lives on’. At the time, the VBKÖ was not able to take this form of apparition as an invitation to, in the words of Jacques Derrida, learn to live with this ghost, to be with this spectre even if it is an objectionable and dangerous one.

Ghosts make demands, they remind us of something that has been forgotten or has not been compensated for. They challenge us. At the same time, through their apparitions, it becomes clear that we can never be sure whether we have actually seen, heard or understood them. Can we trust our senses, our minds, our research, our grappling with them?

For us, ghosts are an indication that there are always dimensions of our being, our research and our engagement that evade us, something that we cannot see nor grasp in its totality. The his/herstory/ies of the VBKÖ are inextricably bound up to ghosts of Nazi ideology and colonial fantasies. Although we may not be able to grasp all of what these ghosts are trying to communicate nor able to deal with them, nonetheless, they send a ghostly signal among the archival materials. They keep messing up tasks that the VBKÖ is trying to accomplish.

Do you feel that the history of Nazi ideology within the VBKÖ can be negotiated in order not to dismiss the organisation as a whole?

In our view, the National Socialist past and its various continuities and incarnations within the VBKÖ definitely have to be addressed. To us, this is intrinsic to a feminist practice and a crucial part of our institutional work. In the case of the VBKÖ, for a very long time, neither its own members nor a broader feminist art scene considered it necessary to do so. For rather different reasons. This is not to say that it is easy to deal with the Nazi past nor that there is a right timing for it. Today, in Austria, there exists the widespread notion that we should be through and done with it.

Still, it is an open question whether it is possible at all to work with such a heavy past. From a positive point of view, one could say an unsettling past bears potential because it challenges our work, our modes of operation — where to organise and produce from, how to do it, what to do and with whom. As an associate of the VBKÖ recently put it, it prevents us from becoming lazy. Seen with a more pessimistic eye, we have also experienced it as a burden, one that, at times, seems to disproportionately demand far more energy when working with the past — its reverberations in and from a present, its present-day hauntings — compared to the (financial) capacities and means we have at hand for such a small organisation.

The film concludes by forming a connection to the ‘spectre’ of migration and the refugee crisis – how do you feel this is linked?

We tried to show that if such brutal ideologies are not called and cast out on the spot they will find their way back and reappear under different guises. In Austria and Germany, there is a definite connection between the ideologies of the National Socialist agenda and the discourse of the exasperated right-wing politics we are confronted with today. Especially in relation to the arrival of people in Europe who are fleeing wars and/or dire economic situations. Links to this past can be found, for example, in specific racist figures of othering, or in the violently exclusive imaginaries of national identities that foster xenophobia. The end of the film thus suggests that various ‘tropes’ of ghostliness can be associated with the current political situation in fortress Europe; uncanny ghosts which loudly defy acts of welcoming; conjured ghosts, which are deliberately invoked by politicians in order to close the borders of Europe, and the ghosts of angst, stereotyping, fake and misleading news. We introduce the topic of migration and its spectres in order to open up a discussion, but since we bring this up at the very end of the film it stays an open issue; something important that has to be looked at, engaged with and dialogued about in order to be able to imagine and work collectively for a radically different future, away from exclusion, discrimination, exploitation and erasure.

What do you see for the future of the VBKÖ?

If we zoom a bit out from the everyday hassle of running the VBKÖ, we hope the association gets the chance to develop further its collective and collaborative approach to running a feminist art space. This will, of course, depend on the people involved in it, as much as on the future of cultural funding in Austria. From within such a collective structure it would be important to keep a continuous discussion of the VBKÖ’s past and how it reverberates in the present. This can happen in very different ways. In recent years, one of our main goals was to support work that reflects upon historical and current subjects from different and intersectional perspectives that take feminist, queer, class, antiracist, de-colonial perspectives into account.

Are you working on any new projects either together or independently?

Together with Veronique Boilard, a curator from Montreal, and Andrea Haas, a Viennese researcher in the field of art pedagogy, we are currently working on an exhibition project called Dark Energy: Feminist Organizing, Collective Working. It will open in March 2018 in the exhibition spaces of the Academy of fine Arts in Vienna. In this exhibition, we seek to explore feminist modes of production and forms of knowledge in the cultural sector from both contemporary and historical perspectives. The exhibition looks at its political stakes in terms of where, what and how knowledge is practiced, created, and distributed. Among the positions we invited are, for example, the London based artists and researchers Althea Greenan and Felicity Allen who will present a performance as well as an installation on the collection of the Women’s Art Library (WAL), today kept at the Library of Goldsmiths University of London. We also invited the artist and archivist Ego Ahaiwe Sowinski who will introduce, together with Aida Wilde, the Women of Color Index (WOCI), which is part of WAL, in a multi-part work.

It is important for us to question how these working strategies are influenced by their respective economic situations. We want to pay attention to the invisible dark matter of cultural production, such as free labour or rampant exploitation. Therefore, we include several positions that look at the structures and mechanisms of independent art organisations—like Annette Krauss’s work on Casco, or Veronique Boilard’s review of the history of the feminist art organisation La Centrale in Montreal—as well as positions that intervene in the structures and processes of dominant institutions such as the project Anti*colonial Fantasies/Decolonial Strategies initiated by students of the Academy of fine Arts in Vienna.

One thought on “INTERVIEW: NINA HOECHTL & JULIA WIEGER TALK HAUNTINGS IN THE ARCHIVE!”