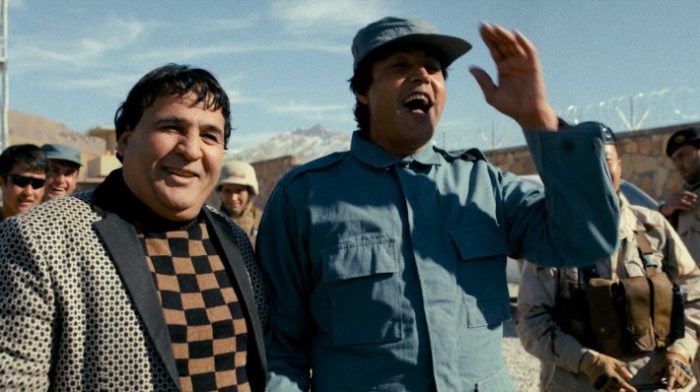

Though Afghan actor/director/producer Salim Shaheen is a formidable talent in exactly none of his chosen fields, his larger-than-life personality brings an unpolished charm to his no-budget cinematic output, as well as making him a uniquely entertaining subject for The Prince of Nothingwood, a funny, often poignant documentary from French filmmaker Sonia Kronlund. A road movie like no other, Kronlund’s film makes a case for Shaheen as a resourceful and eccentric auteur whose work, though technically lacking, succeeds as warmly inclusive escapism for its national audience.

We were fortunate to sit down with Kronlund to discuss the newly released film and the magnetic figure it observes.

So, what’s this film about?

My film is the story of a man who could be summed up as the Afghan Ed Wood. He made 110 films during 14 years of war in Afghanistan – and sometimes 4 or 5 films a month – and he doesn’t know how to read or write. People love his films and he loves making films and there’s a kind of emergency to make films in a country at war.

The Afghan Ed Wood? Is he really that bad?

Yeah! The film is called The Prince of Nothingwood because he says it’s not Bollywood, it’s not Hollywood, it’s Nothingwood. They don’t have any equipment, they don’t have money, they don’t have schools. He has a poor camera, he doesn’t have sound, he has a computer and he’s making movies like a child playing, like ‘Let’s go and make a movie! Let’s play!’

Then why is he so popular?

That’s the question the film is asking. You have a country where there are no filmmakers, there’s no film industry, there’s no money. Even if the film is not very good, people are extremely happy to watch a film that’s shot in Afghanistan with people like them. And his films are always telling stories about poor people, workers, and they’re very happy to see them. ‘Oh, look! This is my street and we’ve made a film!’ It’s an image. They need an image of themselves.

So his work is strangely inspiring?

It is very inspiring. He’s a superstar. Everybody loves him because he’s very funny, he makes a lot of jokes, and there’s a lot of singing and dancing. It’s done with playback, you put on a song, he sings a little bit, so it’s very like Bollywood – cheap Bollywood style.

Is the badness part of the appeal, like the films of Ed Wood?

No, they don’t see it as bad. It’s not our standards but people like it a lot – very common people, people that are not educated, that only see Bollywood. Suddenly Afghan is making Bollywood movies and they’re very happy. They sing their song, there’s a lot of fighting. The appeal is seeing yourself in movies, seeing a movie that’s done in Afghanistan with Afghan language, with characters that represent all the Afghan ethnicities and stuff like that.

And what made you want to cover this filmmaker?

I don’t know!

You just felt you had to?

Yeah, I don’t know why I wanted to…because I’m interested in Afghanistan. I’ve been travelling there for fifteen years and I’ve always done films and documentaries about very hard stories like war and women’s rights and very tough situations and suddenly I find a very funny, lively, joyful character who’s this really incredible, bigger-than-life guy. I said, okay, let’s do a film about this. It will make for a change.

Do you feel western filmmakers can learn anything from this man?

Yeah, they can learn to be more modest and to make film with less money. They can see how he has a real deep necessity to make film. It’s an emergency because it’s such a dangerous country. You don’t know if you’re gonna be living tomorrow so you better shoot your scene today. He’s filming like you can eat a lot – it’s bulimic.

Would you say that the social and political context in Afghanistan plays much into the film?

A little bit, yes. Not so much. It could be somewhere else but it’s fed with a lot of Bollywood movies so what he does is very inspired by Bollywood. The film is like a magnifying glass, and it’s a contrast to war.

What are you working on next?

I don’t know. Maybe Saudi Arabia. I’m interested in Saudi Arabia. I’ve never been there but I think it would be more difficult than Afghanistan.

You’d like the challenge.

Yeah, I hope it’s not gonna be easy.

You don’t like to be too comfortable.

Yeah, and I especially like to do things I’ve never done. I’m curious as well. I could make another film in Afghanistan, Iran very easily but let’s go for tough things.