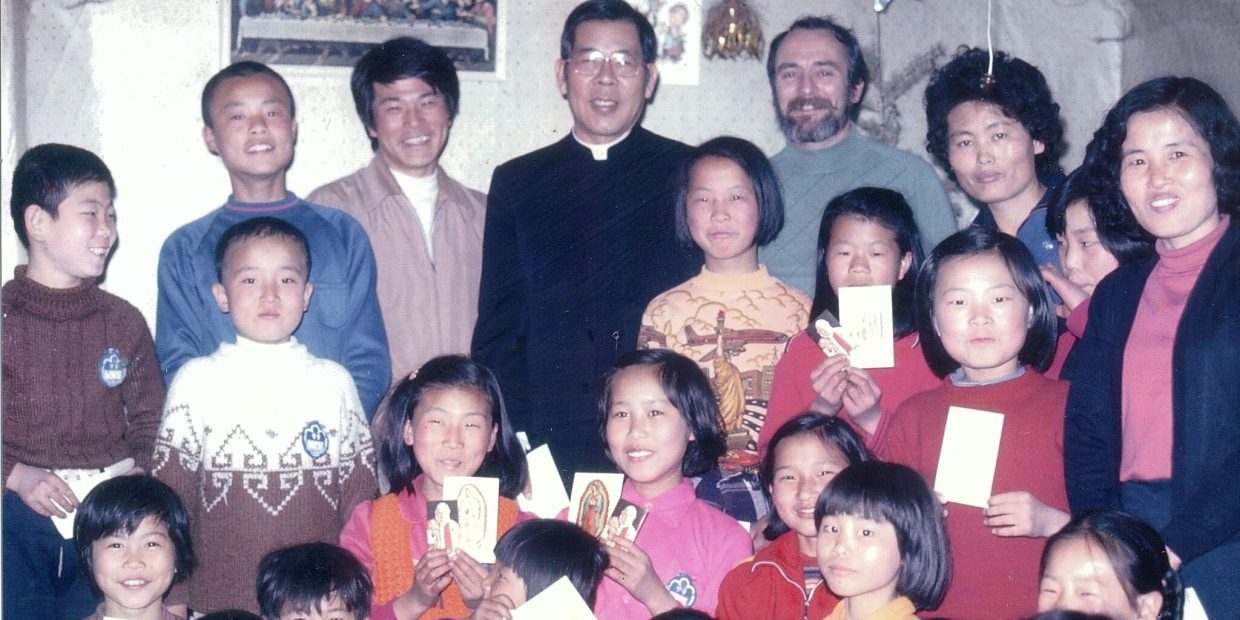

In the reverent Jung Il-woo, My Friend, Korean director Kim Dong-won presents the political tumult and struggles of the urban and peasant communities through the prism of one dedicated activist, charity worker and Jesuit priest. Though Father Jung was born and raised in the US, his decades-spanning affiliations with the farming and shanty town communities of South Korea ultimately suggested a closer kinship to the people of Kim’s nation than Jung’s own, and his presence, in turn, was warmly received by the most underprivileged of locals.

In the reverent Jung Il-woo, My Friend, Korean director Kim Dong-won presents the political tumult and struggles of the urban and peasant communities through the prism of one dedicated activist, charity worker and Jesuit priest. Though Father Jung was born and raised in the US, his decades-spanning affiliations with the farming and shanty town communities of South Korea ultimately suggested a closer kinship to the people of Kim’s nation than Jung’s own, and his presence, in turn, was warmly received by the most underprivileged of locals.

With Jung Il-woo, My Friend screening at the London Korean Film Festival’s recent Documentary Fortnight, we sat down with Kim to discuss this heartfelt tribute and the compassionate character it observes.

When did you first meet Jung Il-woo?

I actually graduated from the same school that Father Jung attended. I entered the university in 1974, but he left at the end of ’73, so I couldn’t meet him in those days but I heard many stories about him already. My seniors told me about Father Jung, so I thought I wanted to meet him some day. But actually I only met him in ’86.

And how did your image of the man change once you met him in person?

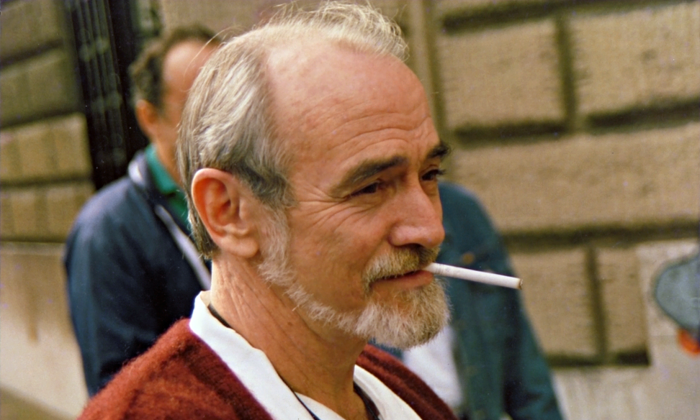

Father Jung was comparatively short, he was bald and he was wearing quite shabby clothes. He was smoking and just had such a modest look, surrounded by these people on the street. His image just fit with the people surrounding him.

When did you decide that you wanted to make a film about him?

I initially wasn’t going to make a documentary about him at all. I was going to make a short clip, to potentially be played at his funeral. And then he passed away, so actually he couldn’t prepare the clip to be played. And then I though I would maybe make some kind of video to share with the people who were around him and care for him. I started to collect materials and discovered a lot of great documentations about him. And that’s when I thought I could make a documentary feature film. That was only after a few months after his death, which was September 2014.

We see in the film how some of the people that Jung helped are reluctant to talk about their experience with him. They’d rather move on. Why did you feel that these experiences and these stories were worth remembering and retelling?

I think of Jung’s life in four different periods. One was when he was a priest and a professor in Sogang, and then after he left Sogang University, and then during his period in Sanggye-dong, and post-Sanggye-dong. So I was with him in Sanggye-dong. I know him very well from that period, but I don’t know him very well from other times in his life. So I found people who knew him from different stages in his life, and I wanted to ask people to say something as if they were writing a letter to him. So they chose something that they wanted to talk about to Father Jung. So I didn’t really choose what they wanted to say about him.

What do you feel is Father Jung Il-woo’s legacy? What impact has his actions had?

He changed my destiny. Not just him, but the Sanggye-dong people and my time in Sanggye-dong completely changed my view of life, my view of film, my view of religion. He is my teacher. But basically, he’s my friend.

Near the end of the film, you imply that the problem of poverty might be getting even worse in Korea. Do you worry for the future?

Yes, in general. There are actually two words in Korean that both mean ‘poverty,’ but I think they have two different connotations. I don’t know if English has a different word for it. I don’t think so. The first poverty is evil. We should get rid of that evil, but it has become worse and worse and I don’t think we can get rid of it. But that first type of poverty I think is kind of social. Society constructs it, and society kind of makes you believe that poverty is something you should be afraid of and you should be ashamed of. That’s when the poverty gets very difficult. Whereas the second type of poverty I’m talking about, you kind of embrace it, and socially really positively accept it. Only that way, I think, can we overcome the issue of poverty potentially.

What are you working on now?

The second part of my film Repatriation. The first part was a story about non-converted, long-term prisoners who came to South Korea from North Korea as a spy. They were captured and arrested and then spent forty or thirty years in prison and released, and then went back to North Korea in the 2000s. Those who had their political faith converted in prison by torture couldn’t go back to North Korea in those days, but they now had this conference stating that this was forced, it wasn’t their own will, so they have the right to be sent back to North Korea. So there is this divide. It will be a story about converted long-term prisoners. But there is no chance for them.