The following feature is compiled from a series of articles published by FilmDoo over the course of 2020, with contributions from William Page, Julio Marmol Corbacho, David Pountain and Weerada Sucharitkul. This article is also available as a free e-book which you can download here.

Introduction

Though the world is beginning to open up once more after a season in quarantine, it’s clear by now that COVID-19 isn’t going anywhere soon, and neither is the pandemic’s multifaceted influence on the many sectors of the film industry.

In order for any movie to make that lengthy journey from the mind of the filmmaker, to the first day of production, to the big or small screen on which you’re viewing it, an astonishing number of things have to go just right, and in these past few months, it seems the pandemic has made a profound impact on almost every step of this process.

For the most part, this impact has been demonstrably for the worse, and we can expect large parts of the industry to spend the rest of this year and beyond attempting to minimise the damage that COVID-19 has wrought. But at the same time, as the pandemic reshapes the ways in which we make and consume media, we are also seeing the emergence of a new set of standards and practices for filmmaking and film viewing that we expect to leave a permanent impression upon the industry, ensuring that things are unlikely to ever go back to the way they were before.

To put it mildly, we are currently in a period of transition, and with this article, we intend to not only reflect on the many ways in which the coronavirus outbreak has transformed the industry, but to also consider some of the long-term changes that the pandemic will bring. While we believe that the crisis has had a significant negative impact on the film industry, we can also see some reasons for optimism as the pandemic changes filmmaking and, crucially, how we consume and even connect with film. Filmmakers who can embrace these changes can potentially do well in a post-COVID-19 industry.

Spanning the sectors, from film production, to distribution, to the international festival circuit, we hope that this article can shed some light upon the strange and volatile climate in which we currently find ourselves, while also providing some insight on the big changes to come.

FILMMAKING IN THE TIME OF COVID-19

Even at the best of times, filmmaking is a precarious line of work, governed by an array of challenging and unpredictable factors, from distribution to funding. With various sectors of the film industry all but grinding to a halt, directors and producers from around the world are finding themselves entering a period of widespread uncertainty and apprehension.

Given that the impact of COVID-19 is likely to last well into 2021, it’s important to understand the immediate short-term and potential long-term consequences on filmmaking.

Job Losses

Just a quick search online will show you an ever-lengthening list of productions and events that have been cancelled or delayed due to the COVID-19 outbreak. Among the higher-profile productions that had to temporarily grind to a halt as a result of the pandemic are the upcoming Batman and Matrix reboots, but this pattern is hardly limited to bigger-budgeted projects.

In March, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE) estimated that COVID-19 had already led to the loss of more than 120,000 industry jobs in Hollywood. Meanwhile, over in the UK, the Broadcasting, Entertainment, Communications and Theatre Union (Bectu) has estimated that around 50,000 industry freelancers will lose their jobs as a result of the crisis. It’s a trend that has spread throughout the sector, with cinemas and other entertainment venues closing down over the same period.

In order to get their projects made, filmmakers are already having to take a variety of logistical and financial issues into consideration. In the case of independent film, making a movie will usually mean taking a personal risk in the hope that your time, effort and expenses will eventually result in a compelling and meaningful piece of cinema that could perhaps advance your career to the next level. For many filmmakers, the current lockdown has made their job all but impossible, but even those with a new film finalised and ready for exhibition are running into difficulty getting their project seen.

As we’ll outline later, COVID-19 is sending ripples through the festival circuit, leading to the cancellation or postponement of events across multiple continents. Though some festivals are adapting to the circumstances, making their line-up available for online viewing, plenty of films have been left without a place to premiere for the foreseeable future. It also doesn’t help that most physical industry and networking events in recent months have failed to go ahead, making it harder for filmmakers to make the appropriate connections to push forward with their next project. This level of uncertainty has made it difficult to plan for the future as we simply don’t know when some sense of “normality” will return.

Shifts in Content Produced

Nonetheless, even in a time when much of the population remains housebound, filmmakers are still finding ways to make the best of the situation. For some people, the prospect of shooting a flick in quarantine has become an appealing challenge to take on.

The enforced lockdown has pushed filmmakers to return to their “indie” roots and to shoot films indoors with Spartan budgets and minimalistic special effects. While it’s too early to tell, this return to the roots of filmmaking may have the positive impact of creating more original films with a focus on storytelling that may also be more profitable in the future given the reduced budgets and likely focus on new forms of distribution.

Sites like No Film School and Mandy, for example, have already launched campaigns encouraging their followers to try their hand at filming a short movie within the confines of their own home. One of the more prominent directors to take up the challenge is Lights Out and Shazam! helmsman David F. Sandberg, who released a horror short in April titled Shadowed that starred his wife Lotta Losten.

Drawing Inspiration from the Crisis

On a more ambitious level, some documentary filmmakers are taking inspiration from the current lockdown as they push forward with their latest projects. Sea of Shadows director Richard Ladkani, for instance, has recently accelerated work on his next feature, and has reportedly discussed the possibility of equipping his subjects with their own cameras so they can document their time in isolation.

Speaking to Deadline, Citizen K and Taxi to the Dark Side director Alex Gibney suggested in March that documentary filmmakers have a part to play in capturing the world-changing events unfolding around them. “We’re in a slightly different position than many businesses in the sense that part of our mission is to observe,” Gibney explained. “Part of our job is to document. And so we have to be attentive to that and also the need to push forward.”

Financial Support for Filmmakers

Of course, not every filmmaker has the resources and connections at their disposal to keep making movies, but there remains a concerted effort from certain corners of the industry to help people through this financially strained period.

The Federation of European Film Directors, for instance, issued a joint statement in April signed by various European groups pushing for “easy and swift access to exceptional financial support” from governments, organisations and cultural funding bodies, listing a series of recommendations that could help sustain the film and TV production sector. At the same time, the British Film Institute has announced a partnership with the Film and TV Charity to create a £2.5m COVID-19 Film and TV Emergency Relief Fund.

Production Begins Again

More recently, however, as lockdown restrictions ease up around the world, we’re beginning to witness the first signs of the industry finding its feet amidst the “new normal.” In the UK, for example, July saw Jurassic World: Dominion become one of the first major productions to resume filming. In preparation, the production spent $5 million on additional safety protocols, including 150 hand-sanitiser stations and 60 extra sinks. These safety protocols, along with enhanced and regular testing are likely to at least enable bigger budget productions to continue shooting even if the pandemic worsens. In the same month, culture secretary Oliver Dowden announced that international film stars, directors and producers would be exempt from quarantine regulations if they are considered essential to the event or production.

Over in France, French culture minister Franck Riester confirmed in June that not only had productions started up again, but that kissing would be permitted on set. In New Zealand, meanwhile, shooting resumed on James Cameron’s long-awaited Avatar sequel following a two-week isolation period for cast and crew arriving in the country. Though many argued that the film should not have been given such an exemption, it only helped to reinforce the importance of the film industry, and especially foreign US investment, in New Zealand.

By contrast, COVID-19 spikes in key areas of California have continued to hold up filming in the United States. As a result, studios in Germany and Hungary have reportedly seen increased attention from US companies looking for alternative locations to shoot their next projects. The film industry is likely to become increasingly fleet-footed as it explores ways to continue production.

In any case, there’s no sugar-coating the fact that we’re moving into difficult times for the film industry, and it remains unclear what state the sector will be in when the dust all settles. In the meantime, we can expect to see filmmakers around the world continue to move forward with their work in whatever way they can, be it through online workshops and networking, or simply using this time to reflect, create and plan for what’s next.

HOW THE COVID-19 CRISIS IS CHANGING THE SHAPE OF INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVALS

As businesses contend with the consequences of COVID-19, we find that film festivals have been particularly hard hit by the outbreak. By their very nature, festivals are heavily interactive events that inspire discussion and debate, as well as serving a crucial role in the communities in which they are founded. Festivals such as Tribeca have played an important part in the rejuvenation of local regions and are a source of collective pride and wellbeing.

They are also key in the release of films from certain genres and in building hype for new projects as they are rolled out internationally. Festivals like Sundance, Rotterdam, Cannes and Toronto are often decisive in the distribution and success of independent and international films, whether it’s through gaining traction and buzz, winning awards or picking up distribution at an attached film market.

Around the world, an overwhelming number of festivals have been either postponed or cancelled entirely for the year. Early examples included the Thessaloniki Documentary Festival and the Prague International Film Festival, both of which were scheduled to begin in March; and the Istanbul International Film Festival, which was set to run from April 10th to the 21st. Closer to home, our friends and partners at Fusion Film Festivals have had to move their Valencia festival from May to October.

The effects of the crisis also extend to numerous genre festivals. Back in March, for instance, the 2020 editions of BFI Flare, SCI-FI-LONDON and the Brussels International Fantastic Film Festival were confirmed either cancelled or postponed. Even the esteemed Cannes Film Festival is no longer expected to commence in its intended form this year, though artistic director Thierry Frémaux has announced 56 titles that will premiere in upcoming festivals under the Cannes 2020 label.

Meanwhile, rather than postponing or cancelling, some festivals are experimenting with moving their events online. BFI London Film Festival, Sheffield Doc/Fest and Locarno Film Festival are just a few of many that have made at least a partial pivot to digital programming as a substitute for in-person events. FilmDoo is working with festivals in this transition online, helping them to experiment with the form their events can take, whether their content is publicly available, behind a pay-wall or viewable in a form that blends the two approaches.

Yet, for film festivals to transition online, there are a number of key issues that need to be tackled:

1. Online festivals often carry a negative stigma that characterises them as ‘fake’ festivals, due in part to the perceived lack of authority and knowledge as to who is watching the films. This can be partly mitigated through having a ratings option for films screened, and perhaps through the use of a small jury to provide a critique or narrative review of the films shown.

2. For filmmakers and filmgoers alike, an online festival may not hold the same sense of importance as a theatrical screening. It’s therefore the responsibility of online festivals to sell their platform as an appealing and prestigious option that will give the appropriate weight to each film. This year’s Ann Arbor Film Festival, for example, presented its entire programme in a series of one-off livestreams, recreating some of the communal atmosphere found at physical events.

3. How films are categorised and nominated, and whether an audience choice system should have a role, are also key issues. Film festivals need to use their online presence to get their followers more engaged and potentially find ways to incentivise their involvement.

4. How the films are shown and charged is also a significant issue, be it on a transactional basis – with the film owner, and potentially the cinema that would have shown the films, getting a percentage of the box office – or through a free online showing intended to raise awareness of the film. This issue has a significant impact on the contracts for content, as screening fees may be needed and issues over the length or structure of online rights would need to be tackled.

5. As ever, piracy remains a key concern. Whatever form the film festivals use to present their content online, they need to ensure that it is as difficult as possible for the films shown to be ripped and reposted elsewhere.

Of course, none of this is to say that physical festivals are a thing of the past for the near future. The Venice International Film Festival, for example, pushed forward with its usual September slot, albeit in a more restrained form. Nonetheless, it’s likely that COVID-19 – and the fear of a similar crisis emerging in the future – will have a considerable long-term impact on the online activity of film festivals, pushing them to build up a more permanent online presence in order to draw followers.

What’s more, the coronavirus pandemic is already raising questions about the benefits and drawbacks of the standard festival format. While the lockdown has inspired debate about the necessity of physical film markets, for instance, this is also a time for film fans to reassess the value of attending big communal events against the cheaper but less social option of watching movies from home. Even before the emergence of COVID-19, many were arguing that the thousands of film festivals being held were simply too many, with festivals fighting for premieres and for the attention of audiences. It’s possible that COVID-19 may have the knock-on impact of “culling the heard” as only the strongest, most established or most innovative film festivals are likely to survive the impact of the pandemic.

As for FilmDoo, we’re currently offering our support to festivals, since we feel they play a crucial role in the release of content, and see them as a foundational cornerstone of the film industry and film culture in general. Nevertheless, we believe that the nature of the role they play in the industry will change, and that they are likely to work more closely with online platforms and technology partners as they adapt to the reality of the 21st century. We certainly welcome the opportunity to be a part of this move.

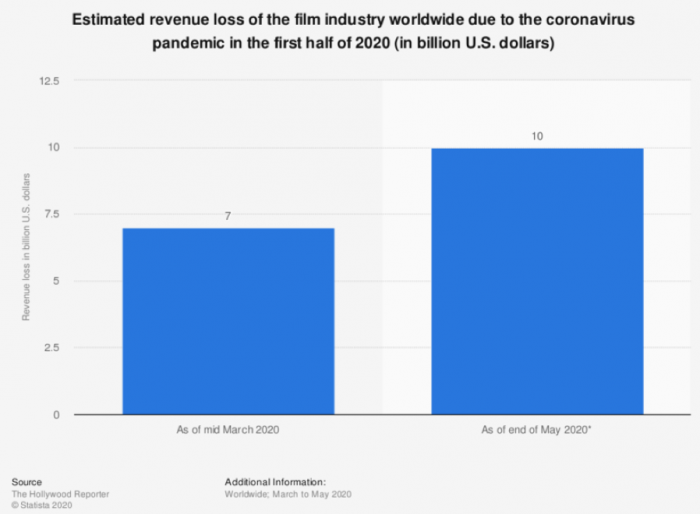

THE SHIFT TO VOD

In the first half of 2020, COVID-19 had a devastating effect on the film industry, with thousands of cinemas shut worldwide and productions halted almost across the board. Yet, there is one sector of the industry that had a demonstrable ‘boom-time’ as a result of the crisis, that being the Video on Demand (VOD) streaming providers.

With people forced to stay inside, many flocked to home entertainment – a development that could mark an enduring shift in consumption preferences across the globe. In response to national quarantine measures, public events and pastimes came to a standstill, leaving consumers with the need to find new, more acceptable ways to fill their free time, much to the benefit of various digital services.

Sure enough, Netflix reportedly more than doubled its target for subscribers in the first quarter of 2020, while other dominant SVODS like Hulu and Amazon Prime Video saw comparable growth over the same period. Ironically, this influx of traffic led Netflix and YouTube to reduce their video bit rates across Europe to help ease the pressure on telecom infrastructure, which can buckle under the increased demand.

Aside from SVOD-based services, ad-supported VOD services (AVOD) such as Roku Channel and Pluto TV have seen significant increases in traffic. During a period where many individuals and families are having to tighten their belts more than usual, there is a clear appeal to such ad-driven services when the alternative is spending money on an array of SVOD platforms. But financial factors aside, these services also have a more varied content focus, often including live national and local news programming options that are not commonly available on most SVOD sites.

What’s more, foreign- and arthouse-focussed platforms such as FilmDoo, Mubi, The Criterion Channel and Fandor have notably benefited, as people begin to look beyond the familiar content of more ‘mainstream’ services in the search for something different. Indeed, here at FilmDoo, we saw a 40% increase in traffic, as people came to the site to rent feature films or to browse our collection of free shorts. Meanwhile, we are continuing to expand our catalogue and will shortly be launching additional innovative features to help people discover more great content from around the world.

No doubt the long-term impacts of the coronavirus will be significant. The pandemic has sped up the growth that we were already seeing from VOD platforms, and has encouraged further experimentation in the release of content. In this next section, we will look into how the spread of COVID-19 has necessitated fresh ideas for distribution, while pushing the industry to find innovative ways of working together to survive the ongoing crisis.

IS THE COVID-19 CRISIS HERALDING A NEW ERA IN DIGITAL DISTRIBUTION?

COVID-19 is having a significant impact on the ways in which films are being released and viewed. Studios have bumped their big releases to months down the line and film festivals have been forced to cancel or postpone worldwide. With cinemas shut down, distributors have had to find new ways to release their content. The result has been some long overdue innovation and experimentation in how films are distributed.

Traditional Role of Cinemas

With the traditional model for distribution, theatrical releases play a crucial role for smaller films in building word-of-mouth awareness, whether it’s through supporting filmmakers and casts on the publicity circuit, or helping to generate reviews. For a long time, major print publications would typically only review films if they had been released in cinemas, even on a limited run basis. However, some publications, such as the New York Times, have now recognised that with cinemas shuttered, a change in policy is needed, effectively giving distributors the go-ahead to release their high-profile titles straight-to-VOD, at least until a proper theatrical release becomes once again viable.

The US Leads the Way in Experimentation

Specialty distributors, especially in the USA, have been at the forefront of the shift to VOD, since they are nimble and agile enough to experiment and make changes that the larger studios are unable to make. Indeed, independent distributors have long pioneered experimentation in the industry, proving instrumental in honing the ‘day-and-date’ release model, which places more emphasis on a film’s home release revenue than its theatrical run. Some distributors, such as Magnolia in the US, have long worked with a variety of VOD platforms to release films online ahead of schedule.

Response from the Independent Distributors

The COVID-19 crisis has led distributors to work more closely with cinemas in something akin to a symbiotic relationship in order to release their films in the only way possible for much 2020, namely on VOD. Kino Lorber, a New York-based distributor of foreign and independent films, has gone even further in focussing on VOD whilst also trying to support the theatres it traditionally worked with. On March 13th, Kino Lorber began to roll out its new Brazilian film Bacurau, an allegorical tale of imperialism, corruption and senseless violence set in a fictional small town in Brazil. Yet, within days, all 60 or so cinemas showing or scheduled to show the film had closed. In response, Kino Lorber brought out a new platform enabling audiences to see Bacurau remotely, while still supporting the theatres where they might have seen the film in the first place.

Available on Apple TV, Roku and Amazon Fire, Kino Lorber’s new initiative is called Kino Marquee and attempts to emulate the moviegoing experience at home. Films are presented on a dedicated web page, each headed by a given theatre’s branded marquee. Revenue from ticket sales are split between the distributor and the cinemas previously scheduled to show the film. The cinemas play a role in promoting their own page, or virtual cinema, via traditional means, including publicity materials, reviews and social media posts. “Ticket” buyers from the theatre’s Kino Marquee site will receive a link that gives them admission to an online screening room, hosted by Kino Marquee’s platform, Kino Now. By the end of March, the initiative had expanded to over 150 theatres in the US.

Kino Lorber is not the only US distributor experimenting in this way. Film Movement, Oscilloscope, Bleecker Street and Music Box Films, for instance, have all been able to get their titles directly online through the use of their own services. Film Movement has created a virtual screening room in partnership with cinemas, and Oscilloscope has made a section of its catalogue available online, including several films that will miss their theatrical windows. The distributor will donate part of the proceeds to the Cinema Worker Solidarity Fund.

In April, Strath Hamilton, C.E.O. of TriCoast Entertainment, suggested that the lockdown will serve as an opportunity for the US-based distributor and sales agent to increase visibility of their own horror/sci-fi/action movie channel, Dark Matter TV. Speaking to FilmDoo, Hamilton argued that since the genre cinema platform is a free service dependent on ad revenue, customer acquisition is “solely a function of consumer marketing, of letting people know we exist.” In the case of Dark Matter TV, Hamilton said that the channel’s typical consumer is “a kind of anti-establishment viewer who rejects the slick mass AVOD channels like Pluto and Tubi and prefers niche destinations who fit with their lifestyle.”

This market is likely to expand rapidly as people look for different forms of content, with niche-focussed channels benefitting particularly well from a newly housebound audience willing to experiment with what they see. The growth of AVOD channels, such as Dark Matter TV, also highlights how distributors are seizing the opportunity to make their long-tail content more readily accessible to a public eager to see more content through different models, whether it’s pay-per-view, subscription or advertising based.

Response of the Studios

Even the major studios have responded to the COVID-19 crisis by speeding up the release of content to VOD. NBCUniversal, for instance, has made The Invisible Man, The Hunt and Focus Features’ Emma available on demand, while Sony set a March 24th on-demand release for the Vin Diesel movie Bloodshot. Likewise, Warner Bros. pushed forward the home release of Ben Affleck-starrer The Way Back, making the film available for electronic sell-through stateside less than three weeks after coming out in theatres, while Lionsgate made its faith-based drama I Still Believe available on premium VOD platforms.

Even the notoriously ‘conservative’ Disney has made significant moves to adjust to the impact of COVID-19 with the release of Pixar animated feature Onward to Disney+ after two weeks in cinemas and, more significantly, the exclusive online release of its big budget action film Mulan. Mulan cost more than $200m to make and was expected to be one of Disney’s main theatrical releases of the year. Yet, after repeated delays, Disney has made the decision to release the film on its new Disney+ streaming service for a high $29.99 one-off purchase fee. In doing so, Disney is not only hoping to recoup some of its substantial investment into the film but to also inflate the subscriber base of its new streaming platform. This is a clear indication that the focus of Disney is on growing Disney+, especially while there remains so much uncertainty with theatrical releases.

In time, this could prove to be a savvy move from Disney. In an international survey conducted by independent analyst and consultancy firm Omdia, it was found that 17% of respondents would rather pay a premium fee to watch Mulan at home than see it in the cinema, though 21% reported that even in the midst of the pandemic, they’d still rather see Mulan in theatres straight away.

To some extent, Mulan can be regarded as a test case for the commercial viability of the premium VOD (PVOD) model. According to Omdia Senior Analyst Sarah Henschel, should the home release of Mulan prove successful, we could be seeing a permanent shift in the theatrical window for major studio releases.

In a time where box office revenue is no longer a reliable measure for commercial success, it seems that the day-and-date release strategy long favoured by many independent distributors is working its way up to the big-budget blockbusters. Of course, it also helps that Disney’s self-owned streaming service ensures profit and control at almost every stage of release.

Arguably the biggest commercial success to emerge from this trend, however, is NBCUniversal’s Trolls World Tour. The animated sequel enjoyed the biggest digital debut ever when it was released straight to VOD back in April, ultimately surpassing the revenue of the original 2016 hit Trolls.

It is surely a reflection of this greater acceptance of straight-to-digital releases that next year’s Oscars will forego the standard rule that a film must be screened in Los Angeles cinemas for a week before it can be considered for nomination. As Academy President David Rubin and CEO Dawn Hudson said in April, “[T]here is no greater way to experience the magic of movies than to see them in a theatre. Our commitment to that is unchanged and unwavering. Nonetheless, the historically tragic COVID-19 pandemic necessitates this temporary exception to our awards eligibility rules.”

Meanwhile, FilmDoo has responded to the coronavirus crisis by working more closely with distributors to get their titles online sooner. Our FilmDoo Services business is working with a range of partners in the industry to help re-focus their efforts to an online release and promotion.

We are focused on providing technical and marketing solutions and services to help cinemas, distributors and filmmakers to survive and, we hope, prosper amidst the lockdown and its aftermath. There has never been a time when digital distribution was more important and relevant than now and we are determined to do what we can to help the industry through this difficult period of change.

THE WORD OF THE DAY: INNOVATION

One recurring theme you may have noticed in this article so far is the suggestion that innovation will be a key factor in the continued survival of the various sectors of the film industry. We can observe innovation not just in the manoeuvres taken by studios, streaming services and festivals as they adjust to new circumstances, but also in the changing nature of filmmaking itself.

Recent speculation, for example, would suggest that virtual production may become a more prominent part of the process for major studios and indie projects alike. The creation of virtual environments and the use of digital technology to shoot remotely hold obvious appeal to producers and directors hoping to get around social distancing measures and travel restrictions.

What’s more, while virtual production is an approach that we tend to associate with big-budget blockbuster spectacles, we’re likely to see smaller productions adopt similar methods as the technology becomes more accessible. So while the aforementioned embrace of day-and-date releases is an example of innovation spreading from the indie leagues to the major studios, virtual production may well be a trend that expands in the opposite direction.

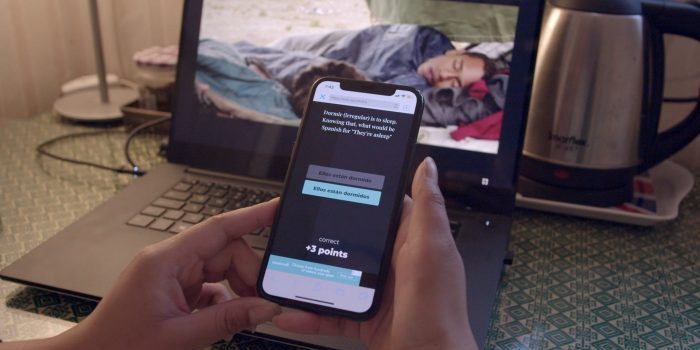

On a more personal note, the COVID-19 pandemic has also pushed FilmDoo to innovate in the development of their online learning tool. FilmDoo.Academy is a game-based edutainment platform that allows for interactive learning through the use of film and video. Earlier this year, FilmDoo partnered with The Language Flagship to pilot the program across major universities in the United States. Since then, however, the spread of COVID-19 has forced schools and universities to take their classes online and find new ways to keep their students engaged and motivated.

In response, FilmDoo separated their edutainment technology from the FilmDoo streaming platform, enabling teachers, tutors and parents around the world to use the tool to turn any film or video content on YouTube or Vimeo into interactive course content.

To a large extent, this was a case of COVID-19 accelerating and modifying developments that were already well on their way, but as we’ll discuss in this next section, the pandemic has also encouraged change in areas and sectors that have been largely resistant to breaking from tradition.

IMPACT ON THE EUROPEAN VOD SECTOR

As we discussed previously, COVID-19 has had a dramatic impact on the VOD sector in the United States. The US market has always been one of the most forward thinking and innovative, with distributors prepared to experiment in how they release, promote and market content.

Outside of the US, however, more ‘traditional’ markets such as France and Germany have largely resisted experimentation in release strategies, instead enforcing more rigid release windows for their films. Nonetheless, we are now seeing evidence that COVID-19 is forcing these more ‘traditional’ countries to embrace alternative release methods.

Experimentation in Germany

In Germany, The Kangaroo Chronicles has become the first domestic film to break the theatrical window by going to VOD shortly after hitting cinemas in March. Usually, films that have received state production subsidies are required to hold to a strict windowing system, which involves a gap of at least three months between a film’s theatrical and its release to VOD. Under these exceptional circumstances, however, The Kangaroo Chronicles distributor X Verleih was given a special dispensation to release the film earlier online.

The film grossed more than $5 million in its initial release in Germany and had topped the box office charts two weeks running before the country went into near-lockdown and cinemas across the nation were shut. The movie was released on 2nd April to VOD at a cost of €16.99, with 15% of the VOD revenue going directly to a new emergency fund, AG Kino and HDF Kino – two national two national associations representing German cinema owners. Similarly, The Hater, the latest feature from Corpus Christi helmsman Jan Komasa, was made available on VOD just twelve days after its theatrical premiere.

Across Europe, regional VOD players, platforms and festivals are offering a wide range of free movies and TV shows, bringing their content to new, ‘captive’ audiences. In Italy, a proliferation of free services, ranging from local streamer TIMvision to the vintage cinema archives of national film entity Institute Luce, have started offering free content and special offers to encourage home viewing. In France, pay-TV group Canal Plus announced back in March that its basic service would be free for two weeks whilst subscribers would get free upgrades. In Spain, leading independent platform Filmin gave away 5,000 free subscriptions to watch movies screened at the Filmin-organised Atlàntida Film Fest.

Forces Resistant to Change

At the same time, Europe’s International Union of Cinemas has told its members not to promote or participate in programs that collapse the theatrical window and send new movies direct to VOD. It has instead encouraged members to seek government support, and has backed European-level initiatives, such as the Temporary Framework for state aid, which would allow cinemas to access grants, state-guaranteed loans and other forms of aid for companies hit by the COVID-19 crisis. While we support these initiatives and believe that governments have an important role to play here in supporting the arts, we think innovation, now more than ever, is key. It is our opinion that theatres need to start thinking outside the box and not be reliant on such state aid support.

Theatres are, at their very heart, an ‘experience’ for the visitors, with the film itself just a part of the larger event of seeing a film on the big screen. As long as theatres focus on the wider experience, they can optimise chances at attracting moviegoers even during these difficult times.

This is why we believe cinemas ought to see VOD platforms as partners and not competitors. Though we recognise theatrical screenings as a fundamental practice of film culture in Europe and beyond, we remain concerned that COVID-19 could again rear its ugly head in some shape or form, either later this year or next year. So for theatres to refuse to innovate their release strategy or find ways to work with VOD platforms is a dangerous policy to take.

With that in mind, our FilmDoo Services business is now working with a range of partners in the industry to help re-focus their efforts to an online release and promotion. We are set on providing technical and marketing solutions and services to help theatres, distributors and filmmakers to survive and, we hope, prosper during this ongoing crisis.

IMPACT ON THEATRES

On an unprecedented level, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced theatres around the world to close their doors, and the consequences of this international standstill are likely to ripple well beyond the recent lockdown.

Widespread Closures

It was back in January when the Chinese government first ordered a shutdown of movie theatres across the country, leading to an estimated loss of $1 billion in box office revenue over the Lunar New Year holiday. While China had reopened about 500 of these theatres by March 23rd, attendance remained low, and by the 27th, they were once again closed.

The lockdown in the ‘Middle Kingdom’ was a sign of things to come in Europe, where the vast majority of theatres in most countries were closed by mid-March. According to a report published by the International Union of Cinemas (UNIC), less than 2% of the 42,000-plus screens in Europe were open by April 1st, a figure that goes up to 4% on a global level.

Impact on Businesses

Needless to say, these shutdowns have served a huge blow to Europe’s theatre industry. In the United Kingdom, for instance, the sector is expected to lose £400 million in ticket sales compared to the equivalent figures from last year, as 52 million moviegoers remain indoors. To make matters worse, most exhibitors in Europe are still expected to pay rent and service charges during the lockdown, though an increasing number of governments have started introducing measures allowing businesses to delay the payment of rent.

The mood is similarly apprehensive over in the United States, where theatres across the country were closed from mid-March. In recent months, big chains like AMC Entertainment have been forced to take new measures to avoid filing for bankruptcy. Collective anxiety remains that the pandemic will ultimately lead to the permanent closure of hundreds or even thousands of cinemas.

In a note to investors released in April, Loop Capital analyst Alan Gould wrote that he expected as many as one quarter of the country’s country’s 40,000-plus screens to close for good in the wake of the pandemic.

Though governments around the world have offered varying forms of support for groups and businesses worst-hit by the COVID-19 crisis, there remains widespread concern about the financial wellbeing of workers in the coming months and beyond. In a survey published in April by the UK’s Independent Cinema Office (ICO), it was found that 37% of cinema employers had made or expected to make redundancies. Out of the workers surveyed, 21% had already had their contracts terminated and 24% had no income.

In the same survey, the majority of independent cinemas estimated that they could only pay their staff at the current level for another two to three months, and while 69% of commercial cinemas were continuing to pay their salaried staff, only 31% were still paying their freelancers and casual staff.

The Shift to VOD

As we’ve outlined in previous sections, the lack of theatres is prompting many distributors to release their latest features early on VOD, one of the few sectors of the entertainment industry that seems to be thriving off the international lockdown. However, there remains some resistance from groups hoping to preserve the immersive and communal experience of seeing a film in theatres.

UNIC, for example, suggested in a statement published in March that this shift in release strategy is not “in the interest of either the sector or audience,” arguing, “With the financial impacts of this unprecedented crisis on our industry still not fully clear, now is not the time to seek short-term financial gains at the expense of the sector as a whole.” Meanwhile, after Universal suggested the possibility of releasing future films into theatres and homes simultaneously, AMC responded by threatening to exclude all forthcoming Universal releases from their cinemas.

Nonetheless, even before the crisis took effect, record-breaking box office figures and studies demonstrating a positive correlation between cinema attendance and hours spent streaming posed a challenge to the old narrative that VOD is harming theatres, and as theatre owners begin to fret about the future, we can assume that more and more of them will see an upside to the rise of streaming services.

One clear example of a theatre chain that has recognised the benefits of having one foot in online streaming would be Curzon Artificial Eye, the UK-based distributor behind both Curzon Cinemas and the corresponding VOD service Curzon Home Cinema. Curzon head Philip Knatchbull has credited Curzon Home Cinema as one of two key reasons for the company’s continued survival (the other being the commercial success of Korean critical darling Parasite). With the release of Kitty Green’s acclaimed drama The Assistant on May 1st, the platform reportedly had its biggest weekend figures to date, marking a 340% increase from last year’s equivalent weekend.

Perhaps it shouldn’t be surprising, then, that AMC ultimately caved to the trends and agreed to collapse the exclusive theatrical window to a minimum of 17 days for Universal releases, taking a portion of the revenue from the film’s premium VOD run.

What Comes Next?

Whether theatres and festivals should or shouldn’t embrace the “virtual cinema” model that some exhibitors are currently trying out is a matter that we’ve discussed in greater detail above, but either way, the task of bringing moviegoers back into cinemas after the lockdown has eased up will surely prove a challenge in its own right.

In the aforementioned ICO survey, the need to re-attract audiences when cinemas reopen is ranked as one of the main concerns of exhibitors, second only to loss of revenue. While some industry chiefs are relying on the appeal of delayed blockbusters like No Time to Die and Wonder Woman 1984 to fill seats, the idea of sitting down in a room full of strangers after months of social distancing is likely to give many moviegoers pause.

Speaking to the New York Post, Wedbush Securities analyst Michael Pachter warned, “Even if we put the virus behind us, lots of people are going to avoid retail and movie theatres till they are comfortable that they are inoculated against the next iteration of the virus.” We have since seen some precautionary measures put in place as theatres around the world begin to open their doors, including shortened hours and staggered seating arrangements to allow more space between audience members.

In England, theatres were permitted to open in the first weekend of July, though not every exhibitor was quick to take advantage of the government’s go-ahead. Cineworld, for instance, waited until the end of July to reopen their theatres, while Odeon saw the gradual opening of venues over the course of the month. Their caution is understandable given the crowds they’ll need to draw: According to Cineworld CEO Mooky Greidinger, the chain’s theatres need to be at least 50% full in order to remain financially viable. Whether this is possible with the need to social distance, especially indoors, remains to be seen.

All in all, it remains unclear when exactly theatre attendance and activity will return to their prior levels, leaving the sector in an ongoing state of limbo. And while we look forward to the day when the big screen experience once more becomes a widely accessible, commercially viable and safe option for exciting new releases, indie or otherwise, the current pandemic could well prove a pivotal moment in reshaping the role played by theatres in the ever-changing film industry.

FILM FINANCING IN THE AGE OF COVID-19

No matter how much we could argue for the artistic value of the medium of film, or root for our favourite indie no-budget project to gain the recognition it deserves, the movie business is still, at the end of the day, a business. And just as the economic repercussions of COVID-19 have spread across pretty much every other industry on an unprecedented scale, the filmmaking sector is no different.

Despite the pre-COVID decline in cinema attendance, one could argue that it’s still quite a lucrative industry during normal times. Last year, for instance, global box office revenue reached an all-time high at $42 billion, while worldwide production and distribution as a whole was valued at an estimated $136 billion.

But how is this value affected when productions are put on hold, expensive safety measure have to be implemented, and the key, “traditional” exhibitors (aka cinemas) are still, for the most part, closed and going through times of great uncertainty? What’s the true scale of this phenomenon? How can one finance their projects these days, and what sort of projects are actually getting the funding they need?

Whether you’re an emerging content creator, a film professional or an industry connoisseur, here’s what you need to know about film financing in the COVID-19 era.

The Bad

Let’s start by going through how films are financed, which is usually, at least in the case of no-studio movies, a combination of public and private funding. Amidst a global pandemic, media funds and film grants were forced to change their schedules and parameters, and, in some cases, lower or close their funds. And while governments in countries such as Canada, the UK and France have come up with partial solutions and forms of support, models across the industry remain severely affected.

In the United States, private funding is the main financing route. In the case of medium and low budget films, this will often mean finance bonds, and, in many cases, these productions were the first to halt as insurance costs rapidly increased. Thus, at the moment, insurance and bonds have reshaped their policies and contracts, often excluding COVID-19 in much the way that other viral diseases like swine flu are habitually left out.

The moral and legal lines on who should be responsible for what are also blurry. In June, Deadline quoted one film exec as asking, “[W]hat’s going to happen if you have a $20 million movie and an actor become incapacitated?” They continued, “The liability is on the producer to cover the gap between $2 million and $20 million.”

The most affected groups? Freelance and self-employed crew and artists, as well as many small businesses working in the supply chain, such as kit suppliers, which are seeing massive losses of business as productions and venues shut down. But even working as a screenwriter – a field that’s proven perfectly amenable to social distancing measures – can be financially uncertain, since fees are often divided into several instalments, with the last (and usually highest) payment being linked to the first day of filming.

The Silver Lining

On the positive side, public and private entities were often quick to lend a hand to those more affected in the business. The partnership between BFI and the Film + TV Charity, for example, created a £2.5m industry-backed COVID-19 Emergency Relief Fund to help support the creative community via donations from a range of industry partners.

Meanwhile, as schedules and workflows are thrown into a state of disarray, passion has become a key motivator for cast and crew – not to mention financiers – when they look for their next project. Moreover, while new financial pressures will be felt across all kinds of movies, the effects generally won’t be as disruptive for the two “extremes” of production budgets.

On the one hand, big studios have different distribution channels, thus enabling them to adapt to the constantly changing circumstances. And on the other end of the spectrum, “guerrilla” filmmakers that were previously accustomed to filming quickly and cheaply will often be less affected by insurance schemes than those working with a bigger budget.

The Future

In most cases, going back to business as usual will not be an option for the foreseeable future. The extra health security and insurance costs created by COVID-19 have made movie financing riskier, while the new safety measures that sets are now adopting can increase production costs significantly.

While there are many different forecasts of the financial repercussions in the industry, what happens next remains uncertain, though that isn’t stopping producers from preparing themselves for the new world. The German Producers Alliance, for instance, is currently lobbying for a default fund to allow productions to continue as planned.

More generally, we know that consumer behaviour is rapidly evolving as the world adjusts to a new way of working, where social distancing, working from home and virtual meetings are the norm. As we’ve discussed above, this new environment has accelerated the rise of VOD platforms and home entertainment options as an alternative to theatres. From this situation emerges the fear that the big streaming portals like Netflix and Amazon, having acquired a bigger share of the market during lockdown, will hold a monopoly on what we see and what gets made, and that truly independent content will get lost in the crowd.

At FilmDoo, we believe in helping these independent and original projects reach the audiences they deserve. That’s why we are now on the lookout for new and engaging films of all kinds to showcase online, be it on our own streaming platform, via our existing partners (including Amazon Prime Video and Vimeo on Demand), or for our new online edutainment tool, which allows students to learn any subject through the medium of film.

If you’d like to learn more about the new production guidelines issued across Europe, check out the European Film Commissions Network’s list here. As for film funding help, BFI has gathered a list of tools for industry members and content owners alike, which you can check out here.

5 THINGS YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT FILM SCHOOLS IN THE COVID-19 ERA

“Go to film school,” they said. “It’ll be fun,” they said. Try going through training for one of the most collective art forms without being able to physically interact with anybody. Difficult, right? Over the course of this feature, we’ve covered numerous ways in which the entertainment industry has been disrupted by the COVID-19 global pandemic, so it probably won’t surprise you to hear that film schools and programmes are no exception.

That being said, here at FilmDoo, we pride ourselves on being a space that helps promote young and emerging film talent, and so we bring you the Top 5 things you need to know about the impact of COVID-19 on film schools and programmes worldwide. Though these tips are partially addressed to both current and aspiring film students, we hope that anybody who considers themselves a cinephile can find some valuable insight in the points below.

1. While the pandemic caught everyone by surprise, it has proved especially challenging for film schools.

Considering that film students are simultaneously, well, students (and, as such, are exposed to all the well-known disruption within the university system) and part of the film community by occupying technical and artistic positions during exercises and short film productions, COVID-19 has presented institutions with a double challenge.

During their tenure at school, students usually learn to chaperone a project from conception to execution, going through the three major stages that are pre-production, production and post-production. During the sudden lockdown, those who were at the pre-production phase (from the script-writing to the planning of the shoot) and post-production phase (everything from the editing process to the final rendering of the film), were the easiest to adapt, since most tasks for these stages could be done remotely.

Production, however, was forced to immediately shut down, and for most schools, their return-to-set date is still unclear, assuming it even happens at all. The safety of students and staff remains the primary concern. However, instructors worldwide remain optimistic. As Peggy Rajski, Dean of Loyola Marymount University’s School of Film and Television, told Deadline, “The great thing about being a filmmaker is, it’s all about problem solving. So, this is a great exercise in that.” A lot of schools faced a difficult situation in reorienting their pedagogy, working out what to teach and deciding how to teach it. The goal? Fostering creativity in the students in a potentially frustrating, limited environment.

2. The response time and measures vary from country to country, and even within regions.

In putting together this section, we examined the reactions and strategies of different schools across the world. After all, each school’s processes and restrictions are determined in part by geographical context. Such is the case for French film schools and programmes like the prestigious La Femis or the English-programmed Eicar, which were forced to shut down operation from mid-March. In America, NYC schools (such as NYU and Columbia film programme) and California (USC and UCLA) followed. At the moment, film programmes and schools based in Latin America (particularly Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Venezuela) are still experiencing heavy restrictions.

Funding of each school also affected how institutions can react. Toronto Film School, a renowned – albeit, private – film programme, handled the situation well, and is slowly making the transition to the “new normal.” Meanwhile, the National Film School of Venezuela has been shut down since March with no signs of reopening. Internet connection in the country is at best precarious, thus making it particularly challenging for online lessons.

It’s also important to understand that film schools are composed of a diverse population, with international students making an average of 50% of the student body. Immigration proves a hefty obstacle to overcome, whether they’re on the inside looking out or on the outside looking in. ICE has recently decreed that if all schools in the United States go remote, international students will not be able to stay in the country, thus putting international students in an even more complicated situation.

3. The biggest focus: graduating students.

When readapting to these extreme circumstances, the first priority was graduating students, since they were the ones coming out to a job market that’s currently even more uncertain than it usually is. As Rajski explained, “We didn’t want people to be penalised for a pandemic hitting, causing them to have to slow down the trajectory they were on.”

As far as online tools go, schools have adopted an “anything that works and is the easiest to access for our students” approach. Speaking to Deadline, acclaimed producer and USC professor Gail Katz explained, “The students and actors will be using Zoom, FaceTime, smartphones, green screen, visual effects, and other technology. It will all be done using social distancing rules—for example, actors filming themselves—with all post [done remotely].”

To keep students and classes on schedule, schools such as the AFI have made classes only accessible in a certain timespan. This sometimes proves challenging for students who are currently residing abroad or those with limited access to internet.

4. For all the problems faced, there are also a few silver linings:

One of the many great things about film studies is that it allows you to get a “safe” feel for the industry and its complex, demanding process. Entertainment is constantly changing, and for many seasoned instructors who are still active members of the industry, this is just one more development that they’re going to have to adapt to. The irony is that the challenges currently faced by faculty and students aren’t unlike those faced in the industry itself. Productions were halted for the better part of spring in many countries, and live shows such as Saturday Night Live have had to reinvent themselves while remaining loyal to their core sensibilities.

As far as shootings go, all schools agree that their students should eventually get the chance to put their knowledge to use, while respecting the safety measures of their respective locations. Through it all, the silent heroes of the transition remain the teachers and instructors, who made the herculean effort of re-thinking an entire semester (and in some cases, student year) in a matter of days. They are currently hoping for the best but preparing for the worst.

After the initial adjustment period, many students have actually enjoyed the change and welcome the challenge. They feel closer to their teachers, and the fact that their creativity is being put to the test has in some ways elevated the overall result.

5. If you’re considering attending film school this year…

Don’t be discouraged by the situation. Most programmes’ applications are currently open, with online support fully operational, and most schools are expected to be back to their normal curriculum within the next few months. If you’re a prospective international student, check the current immigration regulations of the country you’re thinking of studying in. It’s also important to know how the institution you’re applying to handled the COVID-19 situation, and consult on what they are planning to do in the event of a new outbreak.

Alternatively, you could consider an online course in screenwriting, post production or distribution, since these skills can easily be learned remotely.

Get used to change; it’s a part of the industry and, in many cases, it’s what makes it such a dynamic, exciting and rewarding career. As we’ve seen in the international response to the COVID-19 pandemic, you can usually trust in these institutions to find proactive and creative ways of adapting to challenging and unexpected circumstances.

As for those students at the end of their studies who find themselves confronting a frightening future, Rajski had a simple message: “[E]ntertainment ain’t going away. There are going to be plenty of opportunities, now and in the future.”

–

Better yet, these opportunities may be closer than you think. At FilmDoo, we are committed to providing a home to shorts of all kinds, and to collaborating with filmmakers from all backgrounds and level of experience. As long as the content is unique, thought-provoking and original, WE WANT IT.

What’s more, for students keen to get their work out there while earning some money in the process, we’re offering the exciting opportunity to partner with us via the new FilmDoo.Academy platform. In doing so, your shorts could form the basis for interactive online language lessons, accessible from all over the world. Contact us for more info, and keep chasing your dream!

CONCLUSION

Across the sections of this article, we have tried to not only present a helpful and informative summary of the ways in which coronavirus has affected the various sectors of the film industry in the first half of this tumultuous year, but also identify some of the recent trends that seemingly point towards the long-term impact of the pandemic.

As the daily headlines, thought pieces and customer newsletters keep reminding us, we’re living in unprecedented times right now, which means that no one in the entertainment industry knows for sure just what the future holds for film, except that it won’t be the same as what we had before. Nonetheless, by observing how our filmmaking and film viewing habits have changed in the past few months, we can surely see the early signs of things to come.

Many of these long-term changes will be precautionary, as the world attempts to not only prevent the spread of COVID-19 but also pre-empt a similar pandemic at some point in the future. At the same time, however, we can also expect the 2020 lockdown to reshape the film industry for the way it has forced us to reassess what’s important to us and question the practices, sensibilities and assumptions that have been ingrained in this business for years, if not decades.

How much is a trip to the cinema really worth to us? What does a film festival gain when it makes that jump online, and what does it lose? Is VOD really the death of moviegoing? And what does a physical film school have to offer that we can’t learn online for less? In answering some of these questions, we may well find ourselves hoping to rush back to the old ways of doing things from before the pandemic hit, but in all cases, you can expect COVID-19 to leave a lasting mark in some form or another.

As always, film remains a restless medium that’s being constantly remoulded and redefined in response to the cultural, political and technological changes that unfold around it. And while the spread of COVID-19 has seemingly forced us to abandon many of the norms and expectations that once pervaded this business, it will be the innovations of the industry that determine where we go from here.

One thing is certain. Whether for good or for bad, 2020 will be a transformative year in the film industry. The most successful filmmakers, production companies, distributors and sales agents in the industry will be those who can adapt to survive and change to take advantage of whatever opportunities may arise out of the pandemic.

Cover image: Alexandre Chassignon/Flickr