Director: Tsukasa Kishimoto

Watch The Man Who Changed Okinawa on FilmDoo

One man’s training is another man’s torture.

Based on the true story of local legend Hiroyoshi Sai, the coach who led an Okinawan school baseball team to victory, Tsukasa Kishimoto’s baseball biopic, The Man Who Changed Okinawa, is unafraid to explore the real damage sport can have on the body and the mind. It’s a uniquely realistic film in a genre which, while boasting its true stories, often doesn’t pay service to the darkness that lies behind success.

Going in, I expected the sort of underdog-rallying treatment that director Kaspar Barfoed gave the Danish football team in Sommeren 92. Maybe it would have something of the romance of one of baseball’s most famous moments on the silver-screen, Moneyball. But gone is all of the cushy, rose-tinted idealism that makes the traditional sporting biopic so charming. Rather, Kishimoto’s is a film which does not hold back in its swings and does not falter in its hard hits.

Blood, sweat, and tears – the optimism which inspires the film’s title comes very late in the day. The majority of the running time concerns Sai’s brutal training regime. One particular sequence sees the team forced to take laps of the island. Slowly they are whittled down by exhaustion as one-by-one they fall prostrate in the road, dragged to the curb like wounded soldiers. One can’t help but see it as a nod to Full Metal Jacket when Sai stalks his regiment, shouting in their faces. The baseball pitch is akin to a warzone – a parallel which has far greater resonance in the broader scope of the story.

Sai’s gruelling regime is fuelled by more than just a passion for the game. Baseball itself stands for something far more sinister: war. The burns that sprawl across Sai’s back are a crippling reminder of a conflict which refuses to budge in the collective memory. It is believed that Okinawan post-war ends only when they win the championship. Therefore, the baseball league offers a chance to escape the conflict which scars him both mentally and physically. Indeed, Hiroyoshi Sai (Gori) has a haunted stare which speaks of the battlefield rather than the playing field.

Often the players themselves appear like poor drafted recruits. It’s easy to forget that this team is made up of high-schoolers. Very occasionally, a scene will feature one of the boys navigating the ordinary coming-of-age pitfalls of fledgling sexuality or fraternal teasing, serving as an uncomfortable reminder that these are not professional players but boys being pushed to their very limit. One member of the team’s hands are so thick with blisters that he cannot use cutlery in the canteen. This smack of realism resists the sentimental, and makes the team’s success a continual question mark.

Though perhaps secondary to the gruelling training sequences which dominate the film, the baseball games themselves are skilfully shot. The adrenaline of the action, exposed in the intense close-up and the occasional Kubrick-stare, offers a much-needed antidote to the potentially exhausting misery of the training.

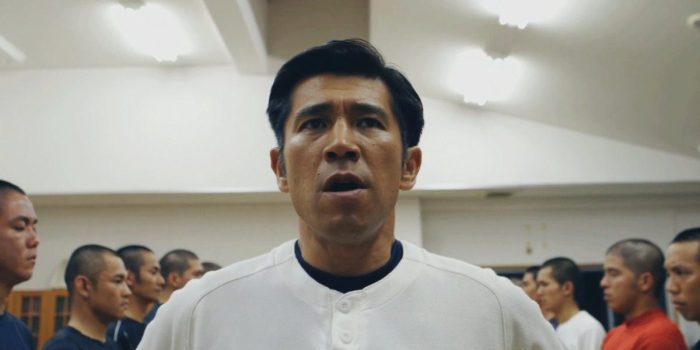

At the centre of the action, however, is Hiroyoshi Sai. Luckily, we are in safe hands, and Gori anchors the film with a balance of inscrutable cruelty and intense sympathy. “I am the rule,” he declares, and for much of the film his unflinching demeanour frustrates with its seemingly baseless brutality. But Gori’s dark, sad eyes offer something far more fascinating.

He is the unexpected heart of a film which eventually, and with much effort, reveals its softer side. The final moments of the film in particular persist in the mind long after the film’s credits. Still stubbornly resisting the mawkishness of the sports-biopic-victory-climax, the balance of grief and victory is delicately handled. Gori’s pitch-perfect central performance is arresting and pays testament to a film which serves its hopeful story with a good deal of regret.