By the time any filmmaker has won themselves the Palme d’Or, it’s usually difficult to question their status as one of the big names of world cinema. Trouble is, that flattering reputation may also come with an unwelcome aura of arthouse elitism, and the films of Turkish director Nuri Bilge Ceylan, at least at first glance, don’t entirely refute these preconceptions.

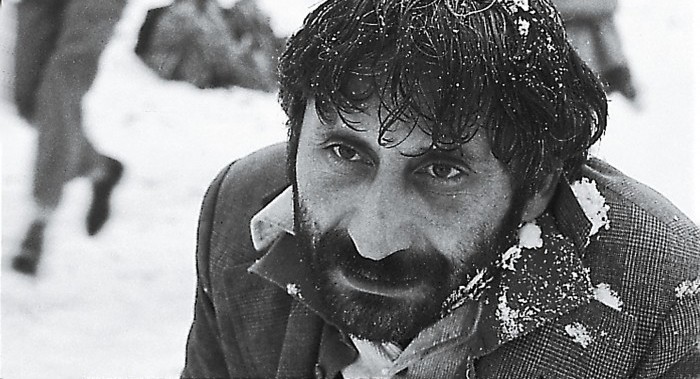

Across his still fairly young career, Ceylan’s work has consistently welcomed such off-putting adjectives as ‘challenging’, ‘serious,’ and arguably the most dreaded of them all, ‘meditative’. His body of work lacks a clear gateway film that presents the director’s patient sensibilities in an especially digestible manner, and while he is undoubtedly a gifted photographer of the elements who is capable of some blindingly pretty landscape shots (drop this man into a snowy setting and magical things will happen every time), his visuals rarely seek to dazzle in obvious and accessible ways. Moreover, though it’s easy to forget just how regularly his films exhibit a deadpan sense of humour, this comedy never overrides the dark moods and worldviews of his pictures, which are bittersweet at their most optimistic.

Still, when Ceylan describes his films as “ordinary stories of ordinary people”, don’t mistake him for another Barton Fink-esque intellectual merely paying lip service to the plight of the common man. Having been in his late thirties by the time his debut feature – 1997’s Kasaba – was released, Ceylan was able to experience life long before he started trying to capture it through the medium of cinema. Hence almost every long silence and stretch of inactivity feels genuine and relatable.

While issues of class and politics often factor into the films of Ceylan, they generally remain as peripheral influences rather than explicit points of focus, much like the roles they usually play in our own day-to-day lives. Rather, his films intrigue more as philosophical and emotional enquiries into some of the universal aspects of human behaviour and existence. None of the following films may exactly be adrenaline-fuelled thrill-rides, but at their best, they can be just as gripping and far more resonant works that feel profoundly tuned in to the rhythms of life.

7. Kasaba (1997)

Nuri Bilge Ceylan has yet to make a bad film but something has to fill the bottom slot, and in a way, it’s inspiring to think that everything the director has made since his highly competent debut has been a step up. The gloriously monochrome Kasaba (aka Small Town) is both one of his most accessible works and the one that feels the least like a Ceylan film, worshipping a little too reverently at the feet of the old masters like Bergman, Bresson and Tarkovsky.

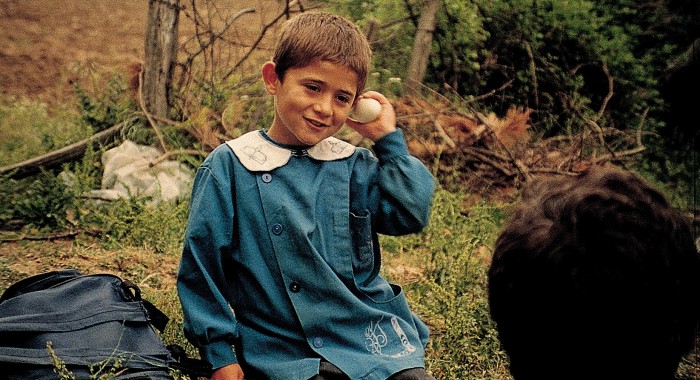

Nonetheless, as far as extended arthouse fangasms go, this is still a damn fine watch, sufficiently showcasing the talent of a relative newcomer with a surplus of good ideas for individual scenes, even if he’s still learning to tie all these ideas together into something greater than the sum of its parts. Ceylan examines with eye-catching imagery such topics as the smallness of any one person’s accomplishments, how we all fit into the grand scheme of things, and the innocent cruelty of children yet to understand age, suffering or cynicism. More than any overarching themes or narratives, it’s the imaginative vignettes that keep the film engaging and memorable, from the lame man slipping in the ice while surrounding children laugh, to the young boy who knowingly dooms a turtle by flipping it on its back. In small, revealing moments like these, Ceylan shows a command of the medium that some directors go whole careers without grasping

6. Clouds of May (1999)

Ceylan’s second feature comes at the tail end of a decade where the film about filmmaking was one of the biggest clichés of indie cinema, and like most of its predecessors, Clouds of May isn’t quite as clever as it thinks it is, so it’s a good thing that it still holds up simply as a carefully observant human drama. In comparison to the arthouse nostalgia of debut Kasaba, Clouds of May feels current in its realism, prefiguring the pacing of Ceylan’s best work with its conversational delivery. The director shows a calm curiosity towards the nuances of people and nature alike, taking the viewers on some spellbinding walks through urban and rural environments. This is the work of an artist who detects subtle life in the smaller details, like a breeze blowing through a field, or an old man’s difficulty in getting his lines right.

That latter case is one example of how the film’s more ‘meta’ aspects are at their most compelling when successfully integrated into the film’s acceptant larger vision of a world where one, figuratively speaking, cannot always plan for the weather. Packed with overt references to Ceylan’s first feature, Clouds of May is, on one level, the exhibition of a man reflecting on his initial steps into filmmaking and figuring out what he has learned from the process. On another, more important level, it is the product of Ceylan putting those same lessons into practice.

5. Climates (2006)

For his first film shot in HD, Nuri Bilge Ceylan decided to step in front of the camera himself, alongside his wife Ebru, in order to capture every wrinkle and tear to cross their respective faces. The director has cited Bergman’s Scenes from a Marriage as one of his favourite films and Climates shows a similar faith in the power of a suffering visage to grip audiences, though with far less reliance than Bergman on eloquent dialogue to tell his story of an ugly and unresolved split.

The film arguably peaks early with a remarkable take of Ebru, as Bahar, quietly weeping as she watches Nuri Bilge’s Isa from afar. As powerful as this scene is on its own, both her sadness and her subsequent cold hostility towards Isa only become truly understandable in the symmetry-satisfying concluding minutes of this patiently delivered character arc, punctuated by sudden and striking moments of sorrow and cruelty. The dejected observations that Ceylan’s previous film, Distant, made on the ultimate loneliness of life and the difficulty of making a connection with another person are boiled down to a single high emotions relationship – an environment where our potential to hurt ourselves and others is at its greatest. Across this desolate landscape of fragile minds, Climates creates a unique and resonant conflict where no rejection or attempt at reconciliation is quite what it seems.

4. Three Monkeys (2008)

While the plot of Ceylan’s murky foray into neo noir sees the director navigating unusually high stakes and overtly political territory, the deeply pessimistic Three Monkeys is as much a dark lament and a ghostly morality tale as it is any kind of thriller. The game of light and shadows the director plays here is characterised by a sickly dullness that is less clear cut than the visual dichotomies most entries in the genre have drawn since the Bogart days. The home of the central family in particular acts as an accommodating setting for some of the gloomiest compositions of Ceylan’s career.

When politician Servet accidentally kills a pedestrian in a hit-and-run, it becomes the first of numerous cases where a character attempts to smooth over consequences with money. Naturally, things don’t go exactly as planned, as Servet, his driver Eyüp and Eyüp’s family get wrapped up in an all-consuming web of conflicts and deceptions where no one is either sinless or soulless. Very little of the brutal actions perpetrated along the way are shown on camera, but through the faces and voices of his talented cast – as well as the pouring rain, cracking thunder and ominous winds that punctuate their conversations – Ceylan channels all the visceral impact one could hope for. Finding more poetry in the aftermath of violence than the incident itself, Three Monkeys creates a crushingly believable world of silent anguish and rampant corruption.

3. Winter Sleep (2014)

The three-and-a-quarter-hour, Palme d’Or-winning Winter Sleep is a film of many swirling elements that Ceylan takes the time to lay out at whatever pace he deems appropriate. The film’s secluded mountain setting is a place characterised by challenging climates and class tensions unfixable by even the most well-intentioned of individual actions. The hotel where the petty, oppressively intellectual Aydin lives with his wife and sister is a cloistered hodgepodge of remnants of history and culture, with old books, posters and masks spilling from the walls. Here, Aydin’s isolation makes room for contemplation, and the philosophical and emotional discourse that makes up the bulk of Ceylan’s film is dense, expansive and natural enough to get lost in.

That everything in the film flows so seamlessly together stems, no doubt, from how it’s all inherently tied to Winter Sleep’s setting, characters and plot. Anchored by sympathetic yet bitter performances from all involved, intriguing ideas are raised before burying themselves in the text and subsequently emerging in new ways via the cast. It’s a strong, ambitious blending of people and concepts, framed by dark, desolate, snow-covered borders, and it’s one of the more poignant marriage dramas of recent years to boot.

2. Distant (2002)

As intriguing as Ceylan’s ’90s features are, it’s still for good reason that the haunting, darkly comical Distant (aka Uzak) was the moment where the director’s reputation transitioned from that of a promising newcomer to kind of a big deal on the world stage. This comes across as the first feature for which Ceylan finally felt wholly secure within his medium, drawing on all the effective ideas from his earlier pictures to create a work of mesmerising purity and stunning originality. It is here, for instance, that the director fully realised the power of the extended take to convey the silence of the lonely and the alienated, and to suggest the fundamental loneliness and alienation of existence.

There is an eerie feeling of futility and quiet panic that hangs over the stories of the film’s two leads – the unemployed Yusuf and the recently separated Mahmut. Neither seem capable of moving forward or backwards in their lives, leaving them mentally stuck in their own private dilemmas like a mouse in glue (image courtesy of one particularly pessimistic sequence). This is a work characterised by the sounds of creaks, drips, drones and other naggingly repetitive noises, because for two characters so emotionally isolated from the world around them, there really isn’t that much to say. In a way, the beauty of Distant lies in how it never really gets started, deftly drawing its story out of an increasingly disheartened state of anticipation. Rarely has cinema given us a work so crushingly profound in its uneventfulness.

1. Once Upon a Time in Anatolia (2011)

The stunningly shot, consistently gripping Once Upon a Time in Anatolia sits right at the top of this list because, in a line, it’s director Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s best marriage yet between his patient, focused style and his diverse thematic content. Every richly drawn character, every captivating image, every despairing moment of existential reflection and every pee joke feels exactly where it ought to be within the calm rhythms of Ceylan’s fatalistic story of a mystery and a tragedy dissected until only an ugly truth remains.

The film’s title may be a reference to Sergio Leone’s 1968 epic Once Upon a Time in the West but Ceylan’s feature arguably has more in common with such classic westerns as 1939’s Stagecoach, 1948’s Red River, 1950’s Wagon Master or even 2010’s Meek’s Cutoff, all of which see their various representatives of society (in this case: a doctor, a corporal, a prosecutor, some cops and a killer) venture into nature and gradually reveal their true characters. Only, while all of the above examples create desperate and dangerous situations to expose the hidden sides of their casts of travellers, Ceylan uses the power of monotony plus time to bring unexpected thoughts and musings to the surface. So, yes, as with the rest of the director’s filmography, there will be many viewers out there struggling to stay awake by the time Once Upon a Time in Anatolia’s two-and-a-half hours are nearing their end, but for those of us susceptible to the lifelike speed of its delivery, this an expansive, trance-inducing, eye-opening work that confirms Ceylan to be a master of sustained mood.

Watch Now on FilmDoo:

(UK & Ireland only)