Dreaming Against the World tells the story of revolutionary Chinese painter Mu Xin through his own words, his work, and the historical context of his life. This short film gains unprecedented firsthand insight into Mu Xin’s artistic career, experiences during the Cultural Revolution, and life abroad.

FilmDoo talks to Dreaming Against the World‘s directors Tim Sternberg and Francisco Bello.

When did you first become aware of Mu Xin and his work, and how was this film conceived?

We became aware of Mu Xin’s work while researching a project that was going to be a look at China’s turbulent 20th Century history during Mao’s reign to the current period of accelerated state capitalism through the experiences of 3 generations of Chinese artists: One older artist, say Mu Xin’s age, another in their middle age and another in their twenties.

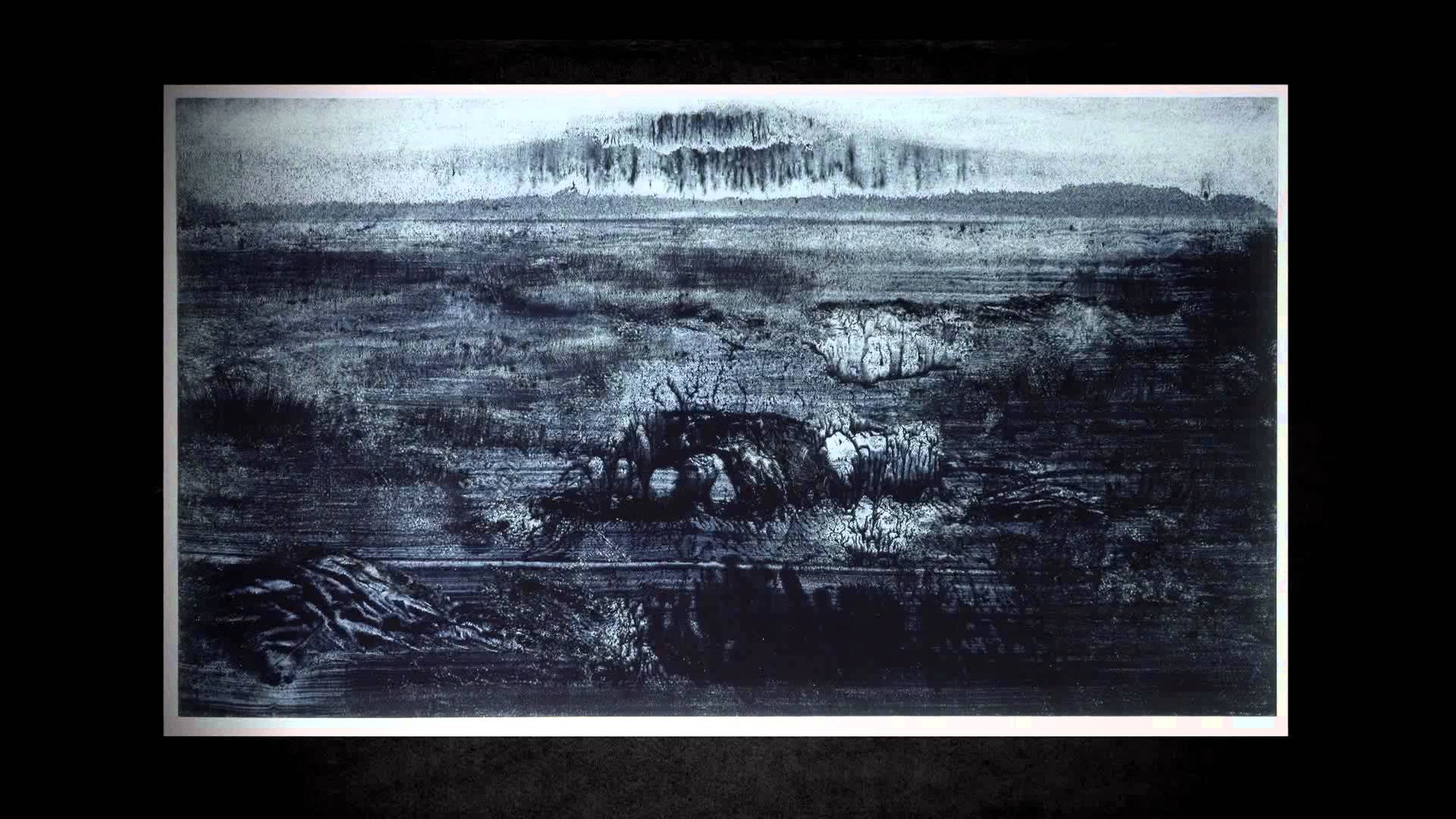

As it was very difficult to get funding and we are not Chinese speakers, we decided to just make a short about Mu Xin. We saw some samples of his ‘Landscape Paintings’ and read about the risks he took to create these and the ‘Prison Notes’ and were really touched by the story and most importantly loved the artwork. At the time we thought he was still living in New York, Queens to be exact, and that it would also be easier to make than a China based film. We then found out that he was back in China through Alexandra Munroe, the Senior Curator of Asian Art at the Guggenheim Museum here in New York and an early discover and supporter of Mu Xin’s. She put us in touch with Chen Danqing, a former student of Mu Xin’s and now a greatly accomplished writer and fine artist in his own right. He is Beijing based and became very excited about the film and agreed to make an introduction to Mu Xin if we were ever in China. We saw this as a great opportunity and, knowing of Mu Xin’s advanced age, got on a plane a few weeks later.

We had to work very quickly as our time in China was short, only a little over a week of shooting in Wuzhen, Mu Xin’s birthplace and where he spent the last few years of his life. As a result, our approach to the story only materialized once we started editing. Ultimately, everything was governed by a simple, but we felt profound, starting point of inquiry: ‘How can painting a landscape be radical?’

How easy was it to approach Mu Xin and get him on board with the project?

We had heard that he rarely – if at all – gave interviews and when he did he could be evasive. Chen Danqing told us that although he would personally make an introduction, he couldn’t guarantee that Mu Xin would agree to do it. And so we were prepared to just call it an accidental holiday in China if we couldn’t get the interview! Then, a few days before we left we saw that a CD by the Emerson String Quartet performing all of Beethoven’s String Quartets was on sale online and we bought it as a gift for Mu Xin. When we arrived there was a few minutes of awkwardness as we were all introduced to each other. We then gave him the CD and he paused for a second and then said ‘You came all the way across the world to give me Beethoven? Okay, what do you want to talk about?’

Still, there were times when we tried to get him to open up about his experiences in prison both before and during the Cultural Revolution and he didn’t want to talk about them. Sometimes he would stop talking and on a few occasions he became very diffident and gruff with us. To him this information was too personal and would, if this film was to be a possible testament, take away from his wish that his work be judged independently from his experiences. But a trust was developed and we were told later by those closest to Mu Xin that he never opened up as deeply with any other interviewers as he did with us.

Your film deals with the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution, in light of this topic did you encounter any discontent around the making of your film in China?

It’s always tricky to say the least when making a film in China but we were lucky. The film was made right before the latest period of censorship and persecution of journalists and artists in China really got underway.

The relationship between the art and the life of the artist is an interesting conflict that Mu Xin points out himself. He tells us: ‘Do not think that the artist is writing an autobiography’. Did you consider this an issue when making the film?

It was an ever present idea when putting the film together. Telling the story was a balancing act between showing the work, in particular the ‘Prison Notes’ and ‘Landscape Paintings’, the biographical aspects of Mu Xin’s life, and the historical periods he was living through. Without this personal and political context of course there would be a far less compelling narrative but we hope that we honored his wishes in spirit.

Do you have any upcoming projects, and would you consider filmmaking in China again?

There are a number of projects that we are considering and hope to make. When there is real information we’ll let you know. It would great to make another film in China, it’s a dynamic, contradictory place.

Watch Dreaming Against the World from the 18th January on FilmDoo!

The film is also having its Hong Kong Premiere on the 18th January at the Asia Society Hong Kong Center. Click here for more info.

Visit the official Dreaming Against the World website here.

Find more documentaries on FilmDoo here.