By Jessica Duncanson

Director: Ju Anqi

Chinese Visual Festival 2017 review

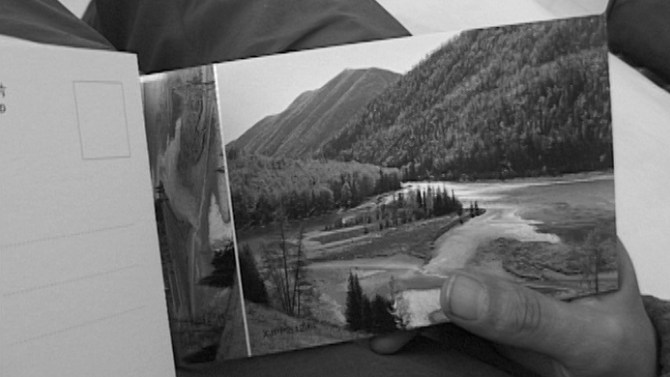

A film that seems to depict everything and nothing, Ju Anqi’s Poet on a Business Trip is a black-and-white existential journey through Western China’s Xinjiang region. Ju was actually born in Xinjiang himself, after his parents were sent there during the Cultural Revolution. In this way, the film’s Shanghainese poet protagonist, Shu, seems to send himself there as a kind of self-exile. Shot in 2002 but left unedited by Ju for over a decade, due to what he regards as complete exhaustion, the film is layered with Shu’s 16 poems. As he travels around the stunningly barren region, checking into hostels and hiring prostitutes, his social interactions and his poems reveal struggles with identity, existence, and creation.

The film may have a tendency to make its audience wonder what on earth the point of it really is, but ultimately that is its strength. Like Ju’s other work, such as Drill Man or There’s a Strong Wind in Beijing, the film is full of largely silent and remarkably unpretentious existential questioning. Ju has previously stated that his work is inspired by Albert Camus and this absurdity is certainly visible in Poet on a Business Trip. Shu appears to be on a constant journey, searching for something that will never be found. This is disguised as a search for desire in bed with prostitutes, or for artistic creation in his inquisitive and often spiritual poems. However, indulging in these things never seems to take away from his larger philosophical and existential exploration. As he broods in his 15th poem: ‘understanding is so necessary’. Yet, it inevitably remains unclear how this understanding can be achieved.

Aside from such grand questioning, a strong consideration of the film seems to be that of what can be hidden in seeming mundanity. The film has a way of shifting from boredom to tragedy with little in between – much like humanity’s unfortunate reality. Sitting by the road on route to the next Xinjiang location, a young child tells him calmly and earnestly about the death of her sibling. Later on, a local prostitute, whose laughter cannot conceal her tragic desperation, asks Shu to take her back to Shanghai with him. By depicting encounters with these people that Shu and the crew met on their journey, the film is a strange and compelling docudrama.

In fact, if the film feels unusual, it’s probably due to this unrelenting realism. We are given a unique opportunity to see the real lives of Xinjiang residents; people that are incredibly rarely given such a stage. In the vast open landscapes of Xinjiang, Shu tries to find meaning and understanding; objectives that may seem obstructed by urban-life, but that are equally as impossible in rurality. As one wise dweller states when discussing rural-urban differences: ‘you envy us and we envy you’. While these blunt insights are valuable, Shu and Ju don’t seem to find what they’re looking for and, arguably, it might have ruined everything if they had.