By Daria Landal

Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. The beginning of Leo Tolstoy’s novel “Anna Karenina” could well be the introduction to the 2001 Argentinian movie “The Swamp”, directed by Lucrecia Martel.

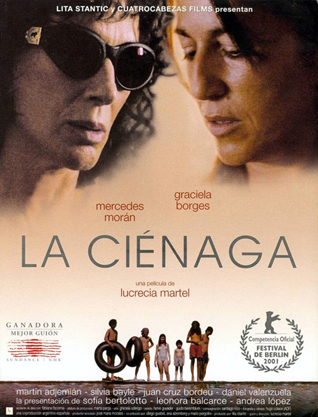

Shot entirely in the Salta Province in Argentina, the films centers on the families of two cousins, Mecha (Graciela Borges) and Tali (Mercedes Morán).

Mecha has a drinking problem, a pack of children and Amerindian servants whom she suspects of neglecting their duties and stealing from her house. Her husband Gregorio (Martín Adjemián) is too obsessed with his looks to pay attention to what’s happening in his house at La Mandragora. He is also having an affair with Mercedes (Silvia Baylé), an office worker in Buenos Aires and an old acquaintance of Mecha’s.

Tali, who leaves in the nearby city of La Ciénega, comes to visit Mecha shortly after an accident that forced her cousin to stay in a hospital. She tries to offer Mecha her help and advice, afraid that Mecha will end up like her mother, who one day couldn’t get up from the bed but died some 20 years after. Tali’s husband Rafael, who takes care of her and the children, advises her against doing too much for her cousin.

Art imitates life ever so closely in “The Swamp”. A casual style of the narrative is reminiscent of the documentary film-making, with quotidian events happening in no particular order and simple but sincere acting on the behalf of most performers. As the story unfolds, the Sword of Damocles is never too far from both families, and covert sub-plots help to build up the tension.

“The Swamp” contains a variety of shocking scenes, particularly one at the beginning of the film, where the character of Mecha falls, dropping glasses and wounding herself, and none of her sun-bathing companions cares even to look at her. Or a scene with a little boy playing with a maimed body of a cat. Or a cow chased by dogs into a bog and dying there slowly, watched by a pack of small children. The shock value is not those accidents themselves, but the indifference of the film characters involved in it.

The film achieves a moody, atmospheric quality in showing family decline in rural Argentina, although it largely scraps the traditional story-telling formula of a looming conflict, climax and resolution in favour of a realistic narrative.