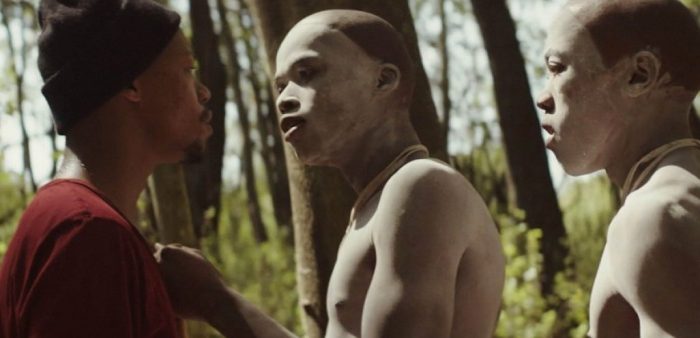

It is an ancient custom of the Xhosa people in South Africa that boys who have grown to a certain age are sent into secluded camps for several weeks where they undergo a circumcision ritual that will mark their transition into adulthood.

This long-standing cultural practice provides a rich context for director John Trengove’s The Wound, in which actor/musician Nakhane Touré stars as Xolani, a Xhosa factory worker supervising the young Kwanda (Niza Jay Ncoyini) throughout his initiation while using their out-of-the-way location as an opportunity to engage in a secretive relationship with fellow mentor Vija (Bongile Mantsai). The tension that simmers between these three emotionally repressed men channels overlapping issues of tradition, sexuality and masculinity as the drama slowly escalates into tragedy.

We sat down with Trengove and Touré to discuss this poignant, controversial work and the complex reality it reflects.

My first question’s for John. What were your intentions when you first came into this project?

John Trengove: About five years ago, we were hearing about human rights abuses on the continent, LGBT people, the death penalty being imposed. But really underpinning it all was this very problematic idea that homosexuality is un-African, that’s it’s kind of a western import that threatens ‘traditional African culture’ in quotation marks. So I think, in a way, the spirit or intention of the film came from this desire to have a story about same-sex desire intersecting with the traditional African practice.

We thought about Robert Mugabe and his statements about this idea that homosexuality is a virus that infiltrates something that is whole and pure. In a way, the story became that as well: this idea of Kwanda as a virus of gayness that comes into this world and begins to affect the universe around him. These were the sort of ideas that were bouncing around. We felt that by bringing these two things together – this rite of passage into manhood with this all-male secret world, and telling a story of same-sex desire in that space – was a potent thing to do.

Nakhane, did you get involved in this film at quite an early stage?

Nakhane Touré: Yeah, about three/four years ago. That’s when John first called me to tell me what the film was about and initially he asked me to possibly score the film. And then a few weeks later he asked me if I’d like to audition. And that’s how I started getting involved in the film, which took a long time actually. So first it was an idea, then at some point I thought it was never gonna happen. And then we started the audition process, which John said took about two years.

And was this your first acting role?

NT: Yeah. First and foremost, I’m a musician.

Was it at all daunting going into this?

NT: I suppose, but when I make a decision to do something, I make sure that I’m gonna do it well, so I throw myself into it completely. So I did a lot of research into how this person was and I dove deep into my past as a Xhosa person who has gone through this rite of passage. It was five weeks of intense self-denial.

So you would say that there are some parallels between your own experience and the experiences of the characters.

NT: Superficially, in the sense that I’m Xhosa, he’s Xhosa, he’s gone through the initiation, I have. And the community in the film, people that I grew up around and knew. So those are sort of parallels. In terms of him as a character, as a person: Nah. He’s quite the opposite of me, I think.

So John, as an outsider to this culture, how did you feel going into this?

JT: Terrified.

Did you feel you had to tread carefully?

JT: Yeah. I was very uncertain about whether this was something that I should even begin to attempt to do. I think there was a long deliberation before this thing really started taking shape. A very important person was Thando Mgqolozana, who was a co-writer, a novelist who’s written a book about the initiation. The thing that characterised the process from beginning to end for me was collaboration.

So I think, much more than anything else that I’ve ever done, I relinquished a lot of control in terms of inviting other people’s experiences to define the shape and textures of scenes and moments. We had a very clear game plan going into it. We had a very clear intention about the story structure but there were a tremendous number of things that happened on set that were kind of surprising. It was almost a controlled experiment that I invited into this space and that was something that I knew I would need to do in order to do this. So it was a departure for me. It was a very different way of working for that reason.

At the same time, Nakhane, as an insider did you feel restricted in any way?

NT: There’s been this in-joke for a while that I have no self-preservation. I knew from the word ‘yes’ and I agreed to be part of this film that I would be bulldozing my way through it. I have my own boundaries which could not be crossed etc. etc., but in general I was never really thinking about what the consequences would be rather than what would make a great film and an authentically South Africa and Xhosa story.

JT: You know, this conversation about insiders and outsiders is a difficult one because there’s so many different ways of framing that. Ultimately the film is about marginal people on the periphery of something, or on the edges looking in. And I think that this is the common ground: That we’re all kind of outsiders, all edgy, marginal individuals in one way or another making a film about the problematic nature of the centre. So there was that thing that bound us together within this cultural embrace, this sort of minefield of making this film.

Do you consider this film to be critical, or simply observational?

NT: Conversational, I think.

JT: I think the film dwells in the grey zone. As much as possible, I try to not push just one idea or agenda but to make the situation as complex as possible, and that’s what I saw my job as being. I’m not standing on a soapbox, I’m not waving a flag, I’m not trying to convince anybody of anything. I’m simply trying to present a situation in as much complexity as I can.

NT: There are no saints.

Would you say that this film also serves as a commentary on masculinity in general?

JT: Yeah, I think it’s speaking to all sorts of different audiences. I think it’s speaking to straight audiences. It’s speaking to female audiences, I think. It started out with the intention to make a queer South African film but really it’s taken on a broader and a deeper meaning than that – or maybe it’s queer. I don’t know. It’s a debate. I think it’s speaking to people from all different walks of life. It’s very interesting to listen to the conversations and reactions to the film.

NT: People who were affected by the problematics of masculinity and patriarchy and, to a level, homophobia as well.

Going back to what you said about western cultures intruding on these other cultures and traditional values: Do you feel that this is a process that’s happening?

JT: Well I’m not quite sure how to define ‘traditional values’ but I see this ritual as something that is ancient but also very resilient.

NT: It’s evolved. It’s changed.

JT: People speak about the fragility of the culture. I don’t really think this initiation is going anywhere anytime soon. There’s something very robust about it. But what you do see and I find very interesting as a storyteller is how it’s rubbing up against an industrial and modern western world. So it’s not something that is preserved in its purity but it’s forced to update and evolve with the times. That process is sometimes a messy one. It’s not always that easy, but I think that was always what was interesting about this story. It was never about presenting a pure idea but about showing the friction that happens when these two worlds rub up against each other.

NT: Culture’s never stagnant. Cultures are always shifting, depending on what’s happening and who’s in power at the time. Geographically, in the region where Xhosa people live in South Africa, it’s all different depending on who’s been touched by what. So the whole idea of what traditional culture is: number one, problematic; number two, you can’t define it really.

And you don’t feel that this change is inherently good or bad?

NT: No, I don’t think it has any moral value. I just think that it’s inevitable.

JT: And it happens all the time. It’s been happening forever. I think we come up a lot against this idea of ownership and the custodians of the culture. Who owns it and who has the right to do it, or to depict it? Whose permission did we ask? These are very problematic ideas. Culture is intrinsically fluid. Culture belongs to the people who make it. That’s been a very interesting part of the process.

NT: Especially as a person who belongs to this culture, who was born into this culture, who is part of the culture. This whole idea of, ‘How could you do this to our culture?’ Well, this is my culture too. Who’s allowed to comment on this? And when? It’s been very interesting, the whole idea of ownership of the culture. And especially for queer people, it’s been a very interesting conversation. Are we allowed to actually have a hand in this culture? And when are we allowed to have a hand in this culture? Also, they talk like the Xhosa people who were involved the film had no agency.

JT: – and as if a story can’t be retold a million times in a million different ways. That’s the beauty of narrative: It exists in an infinite variety, in abundance. If you hate this story, you can tell your own story. I would love it if some closeted kids saw our film and said, ‘Fuck that, that’s not what it was like for me,’ and did some something else. That’s the point.

Have you faced much backlash so far?

(Touré starts to laugh)

JT: (to Touré) You go.

NT: Yeah. There was a little bit of ache in the beginning when the film premiered at Sundance, because up until recently, people really didn’t know what the film was about. They were just reacting to a 2-minute trailer. And so a lot of people sort of jumped to conclusions and thought that the film was an exposé and that it was so disrespectful to the culture. And that we had infected the culture with something that was westernised, which was homosexuality.

As time went by, the backlash intensified and then there were death threats etc. etc. until a week-long run to qualify for the Oscars where a lot of people went and saw that it wasn’t actually what they thought it was at all, which is very interesting because even people who were very vocal about being against the film realised it wasn’t an exposé when they saw it.

Are the Xhosa people a group that gets much cinematic representation?

JT: Well it’s a formidable population group. They’re certainly not a minority in South Africa so the initiation’s also something that’s practised quite widely, but we’re a very diverse country with a lot of opposing and conflicting cultures. There’s always a sense of cultural identity jostling for a position. I think the thing that has really had no real representation is a kind of marginalised queer identity. That is something that I think we really took up in making this film, putting these images on screen first and foremost. I think that was very much a part of that kind of ethos.

So what’s next for you both?

JT: Well Nakhane’s never gonna make a film again (both laugh). I’m developing two projects actually, South African films. One is an adaptation and another one is based on an axe murder that’s happened recently in Stellenbosch. For the time being, I’m going to make films in South Africa and then we’ll see.

NT: I’m working on another project that I can’t really talk about yet. Got an album coming out and I’m writing my second book.

JT: I didn’t know that. That’s great. He’s also a novelist.

So you’re multi-talented.

NT: I like to think so. Or I’m just putting the world through a lot of pain.

JT: Until he finally figures out what he wants to do, one day when he grows up.