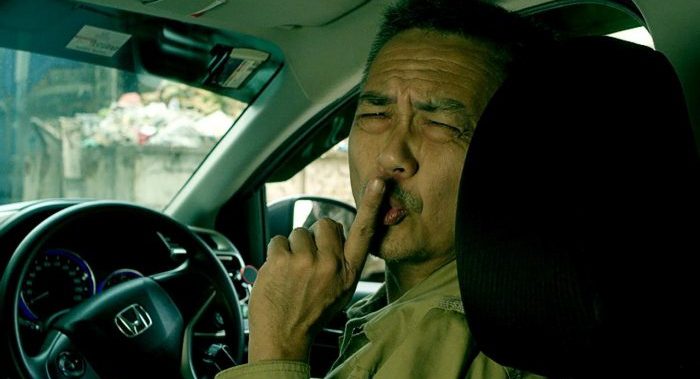

The struggles of an Indonesian immigrant family in Kuala Lumpur forms the sorrowful centre of Crossroads: One Two Jaga, a grimly compelling crime drama from director Nam Ron and producer Bront Palarae. When the young Sumiyati, played by Asmara Abigail, journeys to Malaysia looking for work, she inadvertently enters into a chaotic system of violence and corruption perpetuated by the neighbourhood’s crooked cops and organised crime.

With Crossroads screening at this year’s Far East Film Festival, we met up with Ron and Palarae – later to be joined by Abigail – to discuss this brutal, socially evocative work.

Where did the inspiration for this film come from?

Nam Ron: My inspiration came from immigrant workers. We talked with them and heard their stories. This film tells these stories.

And why did you want to tell these stories?

NR: Because nobody wanted to make this kind of movie. They said that it would be very hard to make. In reality, it’s not very hard but you need to go through the process, which is quite long.

I’ve read that the film had an unusual production genesis.

Bront Palarae: I think it was quite a run around. We went back and forth with the film – testing the limit of what we could show and not show – and the fundraising. We were trying to juggle everything at the same time. After that, we managed to shoot it and then we got kind of stuck in the editing room. We decided to expand the universe further using some of the actors, which meant finding new dates from actors because all of them were busy. So it was a bit expansive in that regard.

So there were fewer stories when this project began and then it all built up from there.

BP: It derived from some of the experiences in interviews – all the workers Nam Ron met – and from there he drafted it. We had like three writers working on the original story and then we had four writers including Nam Ron himself to flesh out the screenplay and then we felt, ‘Alright, this is production ready.’

Do you see this film as political in any way?

NR: I think many countries have these issues, not just Malaysia. When we touch these issues, we’re not pointing at somebody to put the blame on. It’s just a story based on me asking people. Every Malaysian knows about these issues.

BP: It’s political in a way but it’s not a political vehicle of some sort. It’s social criticism, social constructivism of sort. But for me as a producer, I see it as an homage to the people that never get any acknowledgement for contributing to the economic success of our country. They are helping to build our nation and most of them never get to see the fruits of their labours. All of us Malaysians are living a good life out of that labour.

When this thing fell into my lap, I was thinking it pretty much fits with what I have, because my first film Kolumpo was a city adventure about an immigrant. So for me, this was just an expansion of that universe, an homage to those people who work so hard to build our country.

In the film, it all ends very badly for these characters. Is there any hope to be found? Do you see any solutions here?

BP: If you look at just the movie, I don’t really see any hope from how it ends. But when this movie gets made, I think there’s hope because it shows that there’s now a willingness to listen. This type of film has never been done, never been encouraged to be made until now. When they green-lit this, we were like, “Alright, maybe there’s hope in this.”

Nam Ron, you said earlier that this film is not really about blaming people, and it does seem that everyone in this film has their reasons. Could it be said that this whole desperate situation isn’t really any character’s fault? That everybody’s just playing by the rules of the system they’re living in?

NR: It is tricky. These are people who are trying to live. To me, nobody wants to be bad. Everybody wants to be a good person. But sometimes, when you’re in a bad situation, you need to cross the line. I tried to be honest in telling this story. It’s not a propaganda thing. I just wanted to tell this story because this story happened.

Asmara, how did you first get involved in the film?

Asmara Abigail: Bront called me, and I was surprised by that. I didn’t have to go through casting. He was like, “Yeah, take the plane to Malaysia and do the workshop.” I said, “Bront, are you sure? Do you trust me?” because it makes me nervous when you get something from a friend and you didn’t win it by yourself.

Also, when I arrived for the first term of the workshop, I was having a lot of difficulties with the script, with the processes and everything. This was only my second film and my first was a silent film, so I didn’t have to talk. This was the first time I studied the script, the dialogue, how to interact with words, with my colleague actors. So it was a whole new experience. But because of this experience, I’m getting better. If I didn’t start something with a script, it’s not like I could always do silent films because there aren’t many in this century!

How would you describe your character?

AA: She’s a very young girl from a little village in Java where there’s nothing to do. Everyone is farming, and in the village it’s basically just old people, because all the younger people go abroad to do these kinds of jobs. So of course, in your mind, you think you have to go abroad as well. You have this idea of the big metropolitan city: you go there, make a lot of money, send money to your family and then build good, proper houses.

It’s a sweet dream but then, when you arrive, what you have to do with the contract is different. You have to work 24 hours without any breaks. You live inside the house with your masters. You have to do all of the jobs for the house. Also for the garden. Also for the kids. Also maybe for the grandma. Everything. It’s like you don’t have a life of your own. You cannot even go outside just to breathe.

She’s very young. Of course she wants to break free because it’s not what she imagined it was going to be. And of course she’s going to have a lot of problem with the payments. They don’t want to pay you and they take your passport so you can’t go anywhere. So there’s a lot of conflict like that. In the end, you just want to escape. But the like boss of the mafia asks, “Can you swim?” This is kind of the hottest issue of the period, about immigrants and the sea.

So it’s not too surprising that people feel they have to turn to crime.

AA: Yes.

BP: A lot of people die when they cross illegally over the sea.

Do you feel that this is an important film you’ve made?

AA: It’s very important, especially for Malaysians. It’s about corrupted police. All the negotiating that Bront and Nam Ron and Rozi (Isma Abdul Karim) did was very hard. And every time I talk to someone about how Bront wanted to do a film about Malysia’s corrupt police, they’re like, “Can he do that?” because it’s just impossible. They can just put them in jail. Just joking! But it’s very hard.

BP: It’s also a reconciliation between Malaysia and Indonesia, because a lot of our workers are imported from Malaysia and there’s never been a story that explored that dynamic, that kind of relationship between the two countries. It’s about digging that truth out and presenting it to both societies, not only Malaysian audiences but Indonesian as well.

AA: There are a lot of events around illegal workers from Indonesia. There are a lot of problems in Malaysia, Singapore, Middle East and Hong Kong but I think there aren’t a lot of movies that tell these stories.

Last question: What are you all working on next?

BP: I’m working on two projects. One is my directorial debut. It’s called The Intern. And as a producer, I’m working on what I think is the final film in my immigrant trilogy. It’s about the modern day slavery of apple pickers from Malaysia that get stuck in their work.

AA: My next project is with Yosep Anggi Noen. The last project he made was Solo, Solitude. This one is science-fiction.

NR: I’m still in the process of writing my next project. I shoot around August this year. It tells a story about showbiz in Malaysia and how difficult it is to make a theatre production. It’s like Birdman.