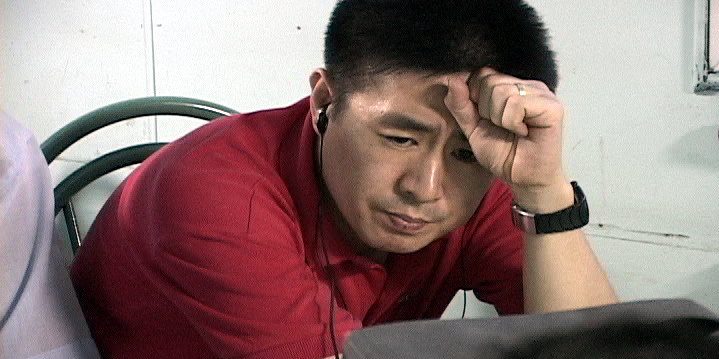

Park Kiyong (b. 1961) is a singular figure in Korean film culture: a KAFA graduate who went on to combine a filmmaking career with a key role in film teaching at KAFA itself and at Dankook University.

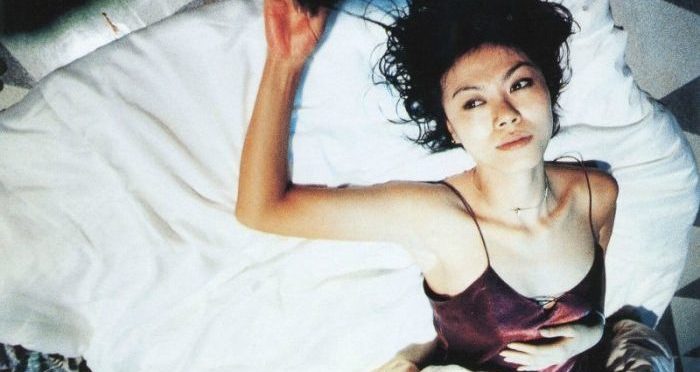

As a director, Park’s breakthrough came with 1997’s Motel Cactus, a downbeat drama lensed by Christopher Doyle and co-written by Bong Joon-ho that observes a series of intimate encounters in a Gangnam ‘love hotel’. Following on from that award-winning work was 2001’s Camel(s), a heavily improvised depiction of an extramarital affair that would mark a shift into independent filmmaking.

Though much of Park’s output this decade has taken the form of documentaries and essay films, the director made a return to narrative fiction with last year’s Old Love, a feature that focuses once more on a romantic encounter, but from a newly mature perspective.

Ahead of his visit to the London Korean Film Festival 2018 (LKFF), Asian cinema expert Tony Rayns asked Park a few questions.

TONY RAYNS: You make both fiction films and documentaries. Are the two closely related for you?

PARK KIYONG: For me, fiction and documentaries are the same. If I come up with a story I want to make, I go for fiction. And if I find some interesting place (I am mostly attracted by places), I make a documentary.

I realised recently that whether I go with fiction or documentary, I always end up making an essay film. I have no idea how I got into this habit but, more and more, I feel I don’t want to restrict myself in any way. I just let the brushstroke lead me.

Your three fiction features all deal with short-term sexual relationships. Any special reason why you chose to focus on this topic?

I am drawn to dealing with short-term relationships because they can condense the story and reveal characters in an interesting and economical way. Since I make low budget films, I am very much concerned with how to tell a story without spending big money.

Beyond that all my characters long for on-going relationships, but they don’t succeed in achieving them. I believe maintaining a long-term relationship, which we all wish to have, is almost impossible in this complicated modern society for all kinds of reasons.

Ever since Motel Cactus in 1997, you’ve chosen to work independently. What are the main pluses and minuses of going independent?

Even from the beginning, I felt uncomfortable working in the film industry. This is because (as an old friend wisely pointed out a long time ago) I am a control freak, and I want to control things myself rather than being controlled by somebody else.

The good side of working independently is that nobody tells you what you can or can’t do, and the bad side is that you are always short of everything.

The fiction films look quite different from each other, and presumably not only because different cinematographers shot them. Can you say something about the changing visual strategies?

I try to find the right style for each film. For me, style or form is as important as the story, maybe more important. I often start a film with a style in mind and try to find a suitable story for it.

Since I make low budget films, I can’t always do whatever I think is the best for the film. I often have to find alternative ways of doing things within the prevailing conditions, which are normally very limited. This can also define the style.

Has the way you work with actors changed from film to film?

It really depends on who I get for the film. Since Camel(s), improvisation has become my main directing tactic and I try to develop it in my own way, but, so far, I’ve not been so lucky in finding the right actors for this approach to filmmaking. I am not that happy with the results.

Do you fully script your fiction films before you shoot? Do you storyboard them?

I have written a full script for all my fiction films except Camel(s), but the script is only a guide map for further developments. Some actors coped well with this way of filmmaking, but some hated it even though they had agreed in the first place. No doubt this is because I am as fickle as a cat’s eye, always changing my plan and throwing them into confusion.

I do storyboard in detail, but when we’re on the location to shoot I tend to change everything, reacting to whatever we find there at that time. I do think about howthe material will be edited, but more often I go wherever my fancy takes me and don’t give a toss about what will happen when I come to edit. Then I repent later.

Has your teaching work in KAFA and Dankook had any bearing on your filmmaking?

Certainly. I couldn’t make a single film for 10 years while at KAFA because I was too busy with the school work. At Dankook I have more free time to spare, but I can only make films during the breaks, winter and summer. In a way, that determines what kind of films I can make.