Director: Hong Sang-soo

London Korean Film Festival 2019 review

Like a single cell repeatedly dividing and mutating to form a complex organism, the fragmentary structure of Grass suggests a work that’s continuously copying, expanding, and defining itself before our very eyes. With each new vignette, Hong Sang-soo’s mysterious and melancholic drama offers a thoughtful evaluation and extension of what came before, ultimately justifying the director’s tendency to revisit the same themes and scenarios with every project, even as it channels the underlying despair of all this repetition.

Though the film never runs out of intriguing new angles from which to analyse itself and its themes, the world that Grass occupies is deceptively small. The various conversations that comprise Hong’s monochrome vision unfold in and around the same small café in what looks to be the span of a single evening, each drawing from a rotating line-up of a dozen or so recurring characters.

Since this is a Hong joint we’re talking about here, most of these contemplative figures are involved in the arts, and in their poignant, often insightfully awkward exchanges, a few common subjects emerge, most notably death and suicide. Reflecting Hong’s own creative habits, many of these despondent men and women seem stuck in a miserable loop, and so most of these conversations end in a manner that feels affectingly unresolved.

Repetition is both the unfortunate pattern of these characters’ lives and a powerful tool in the hands of Hong, whose approach is best exemplified in a striking interlude that sees writer Ji-young (Kim Sae-byuk) ascend and descend a flight of stairs over and over again, as though caught in the cycle of an obsessive-compulsive ritual. With each new go-around comes endearing variations, and as Ji-young’s movement grows more spirited, what was once exasperating becomes strangely exuberant.

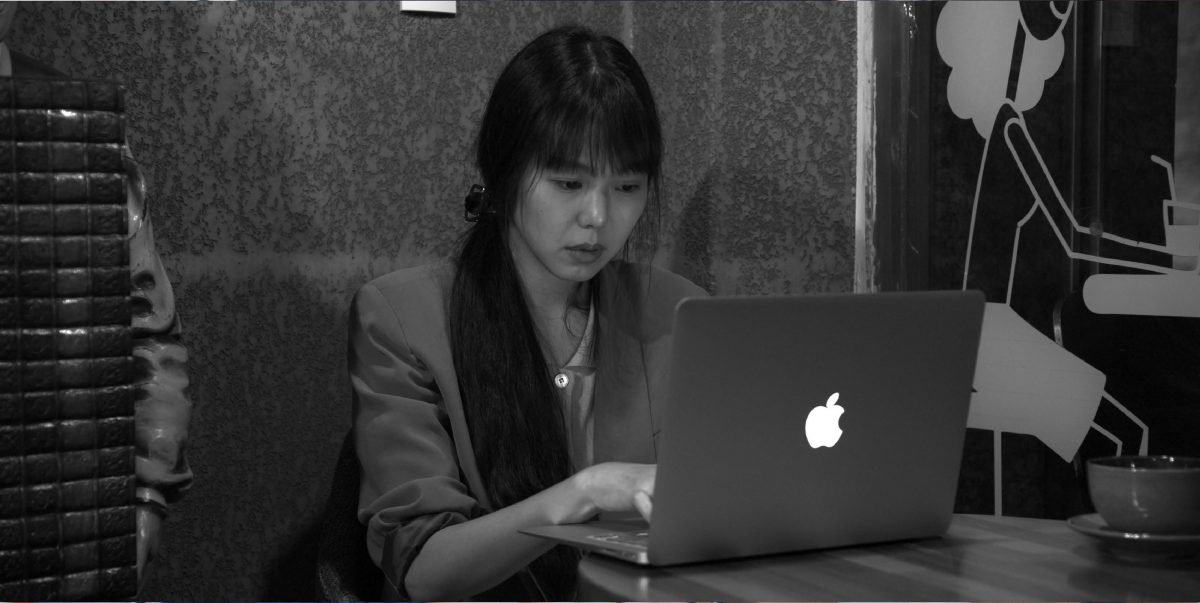

But common themes aside, the many segments of Grass are also connected by Hong’s trademark self-reflexivity, as the café’s various patrons observe, discuss, and draw inspiration from the conversations happening around them. Kim Min-hee’s character A-reum in particular serves as an obvious stand-in for the director as she sits behind her laptop and comments on each discussion by way of her internal monologue.

Though A-reum seems content to eavesdrop from her own corner of the room, her sense of remove is challenged every time a character attempts to strike up a conversation with her, proving that she’s every bit as “in it” as the people she analyses. After a tense exchange with her brother (Shin Seo-kho) and his fiancée Yeonju (Ahn Sun-young), A-reum’s place in the drama momentarily shifts from observer to object, as her family reflects on her confrontational behaviour and characterises her as a bitter spinster. This inversion later reaches its lonely endpoint in a scene of A-reum wandering the streets unaccompanied, with no one left to remark upon but herself.

And so this ongoing process of self-assessment continues right through to the end of Grass’s compact 66-minute runtime, by which point, the film’s many parts have become tightly interwoven yet its whole feels beguilingly vague. For all its analysis and autocritique, Hong’s new feature remains as enigmatic as anything the director has brought us in recent years, leaving us once more with the impression that the auteur’s pet concerns still have plenty more truths left to relinquish.